By Sean Lang

When the late historian Sir Ben Pimlott embarked on his 1996 biography, his colleagues expressed surprise that he should consider Queen Elizabeth II worthy of serious study at all. Yet Pimlott’s judgement proved sound and, if few academics have followed his lead, the political role of the monarchy has received thoughtful treatment in the creative arts.

Stephen Frears’s 2006 film, The Queen, showed her dilemma after the death of Princess Diana; Peter Morgan’s stage play The Audience showed the monarch’s weekly meetings with her prime ministers. And she has been shown in a generally positive and sympathetic light by both Netflix’s acclaimed drama series The Crown and even in Mike Bartlett’s speculative play King Charles III, about the difficulty her heir would have in filling her shoes.

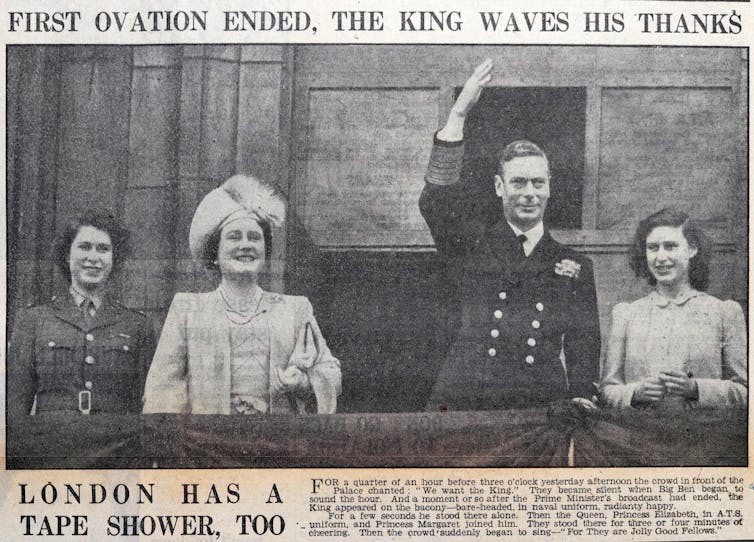

Elizabeth’s reign was a delayed result of the abdication crisis of 1936, the defining royal event of the 20th century. Edward VIII’s unexpected abdication thrust his shy, stammering younger brother Albert onto the throne as King George VI. Shortly thereafter he was thrust into the role of figurehead for the nation through the second world war.

Kathy deWitt/Alamy Stock Photo

The war was the most important formative experience for his elder daughter, Princess Elizabeth. Her experience as a car mechanic with the ATS (Auxiliary Territorial Service – the women’s army service) meant that she could legitimately claim to have participated in what has been called “the people’s war”.

The experience gave her a more naturally common touch than any of her predecessors had displayed. When, in 1947, she married Philip Mountbatten – who became Duke of Edinburgh (and died in April 2021 at the age of 99) – her wedding was seized on as an opportunity to brighten a national life still in the grip of post-war austerity and rationing.

Elizabeth II inherited a monarchy whose political power had been steadily ebbing away since the 18th century but whose role in the public life of the nation seemed, if anything, to have grown ever more important. Monarchs in the 20th century were expected both to perform ceremonial duties with appropriate gravity and to lighten up enough to share and enjoy the tastes and interests of ordinary people.

The Queen’s elaborate coronation in 1953 achieved a balance of both these roles. The ancient ceremony could be traced to the monarchy’s Saxon origins, while her decision to allow it to be televised brought it into the living rooms of ordinary people with the latest modern technology. Royal ceremonial was henceforth to be democratically visible, ironically becoming much better choreographed and more formal than it had ever been before.

The Queen went on to revolutionise public perceptions of the monarchy when, at the urging of Lord Mountbatten and his son-in-law, the television producer Lord Brabourne, she consented to the 1969 BBC film Royal Family. It was a remarkably intimate portrayal of her home life, showing her at breakfast, having a barbecue at Balmoral and popping down to the local shops.

Prince Charles’s investiture as Prince of Wales the same year, another royal television event, was followed in 1970 by the Queen’s decision during a visit to Australia and New Zealand to break with protocol and mix directly with the crowds who had come out to see her. These “walkabouts” soon became a central part of any royal visit.

The highpoint of the Queen’s mid-reign popularity came with the 1977 Silver Jubilee celebrations, which saw the country festooned in red, white and blue at VE Day-style street parties. It was followed in 1981 by the enormous popularity of the wedding at St Paul’s Cathedral of Prince Charles to Lady Diana Spencer.

Testing times

The following decades proved much more testing. Controversy in the early 1990s about the Queen’s exemption from income tax forced the Crown to change its financial arrangements so it paid like everyone else. Gossip and scandal surrounding the younger royals turned into divorces for Prince Andrew, Princess Anne and – most damagingly of all – Prince Charles. The Queen referred to 1992 – the height of the scandals – as her “annus horribilis”.

The revelations about the misery Princess Diana had endured in her marriage presented the public with a much harder, less sympathetic image of the royal family, which seemed vindicated when the Queen uncharacteristically miscalculated the public mood after Diana’s death in 1997. Her instinct was to follow protocol and precedent, staying at Balmoral and keeping her grandchildren with her.

This seemed hard and uncaring to a public hungry for open displays of emotion that would have been unthinkable in the Queen’s younger days. “Where is our Queen?” demanded The Sun, while the Daily Express called on her to “Show us you care!” insisting that she break with protocol and fly the Union Jack at half-mast over Buckingham Palace. Never since the abdication had the popularity of the monarchy sunk so low.

Caught briefly on the back foot by this remarkable change in British public behaviour, the Queen soon regained the initiative, addressing the nation on television and bowing her head to Diana’s funeral cortege during a cleverly conceived and choreographed televised service.

The extent to which she quickly regained public support was shown by the enormous, if unexpected, success of her 2002 Golden Jubilee, which was ushered in by the extraordinary sight of Brian May performing a guitar solo on the roof of Buckingham Palace. By the time London hosted the Olympics in 2012 she was sufficiently confident of her position to agree to appear in a memorable tongue-in-cheek cameo in the opening ceremony, when she appeared to parachute down into the arena from a helicopter in the company of James Bond.

Political sphere

Queen Elizabeth kept the crown above party politics, but she was always fully engaged with the political world. A firm believer in the Commonwealth, even when her own prime ministers had long lost faith in it, as its head she mediated in disputes between member states and provided support and guidance even to Commonwealth leaders who were strongly opposed to her own UK government.

Her prime ministers often paid tribute to her political wisdom and knowledge. These were the result both of her years of experience and of her diligence in reading state papers. Harold Wilson remarked that to attend the weekly audience unprepared was like being caught at school not having done your homework. It was widely believed that she found relations with Margaret Thatcher difficult.

The Queen and the Duke of Edinburgh sometimes objected to the political use to which governments put them. In 1978 they were unhappy to be forced by the then foreign secretary, David Owen, to receive the Romanian dictator Nicolae Ceausescu and his wife as guests at Buckingham Palace.

The Queen could act to very positive effect in international relations, often providing the ceremonial and public affirmation of the work of her ministers. She established a good rapport with a string of American presidents, particularly Ronald Reagan and Barack Obama, and her successful 2011 state visit to the Republic of Ireland, in which she astonished her hosts by addressing them in Gaelic, remains a model of the positive impact a state visit can have.

She was even able to put aside her personal feelings about the 1979 murder of Lord Mountbatten to offer a cordial welcome to the former IRA commander Martin McGuinness, when he took office in 2007 as deputy first minister of Northern Ireland.

Only very occasionally and briefly did the Queen allow her own political views to surface. On a visit to the London Stock Exchange after the 2008 financial crash she asked sharply why nobody had seen it coming.

In 2014, her carefully worded appeal to Scots to think carefully about their vote in the Independence Referendum was widely – and clearly rightly – interpreted as an intervention on behalf of the Union. And in the run-up to the 2021 UN COP26 conference in Glasgow, from which she had to pull out on medical advice, she was overheard expressing irritation at the lack of political action on the climate change emergency.

Final years

As she approached her tenth decade, she finally began to slow down, delegating more of her official duties to other members of the royal family – even the annual laying of her wreath at the cenotaph on Remembrance Sunday, while in May 2022 she delegated her most important ceremonial duty, the reading of the Speech from the Throne at the State Opening of Parliament, to Prince Charles.

She retained her ability to rise to a crisis, however. In 2020, as the COVID pandemic descended, the Queen, in sharp contrast to her prime minister, addressed the nation from lockdown at Windsor in a calm, well-judged message. Her short address combined solidarity with her people with the reassurance that, in a conscious reference to Vera Lynn’s wartime hit, “We will meet again.”

The decade also brought sadness. Her grandson, Prince Harry, and his wife Meghan Markle withdrew completely from royal duties, causing deep hurt to the royal family. This hurt was compounded when the Sussexes accused the royal family, in an interview with Oprah Winfrey which was watched around the world, of treating them with cruelty, disdain and even racism.

The shock of the interview was followed quickly by the death of Prince Philip, her husband of 73 years, a few months short of his 100th birthday. At his funeral, which was reduced in scale to meet the requirements of COVID regulations, the Queen cut an unusually lonely figure, small, masked and sitting alone. As her health declined in the months following his death, the deep impact of his loss became all too apparent.

The pain of the Sussexes’ estrangement from the royal family was heavily compounded by the disgrace soon afterwards of Prince Andrew, her second and, it was often suggested, her favourite son. His close involvement with the convicted American paedophile, Jeffrey Epstein, led to the unedifying spectacle of a senior member of the royal family being accused in an American court of underage sex; he made his own position immeasurably worse by agreeing to a disastrous interview on the BBC current affairs programme Newsnight.

The Queen responded to the scandal with remarkable decisiveness: she stripped her son of all his royal and military titles, including the cherished “HRH”, and reduced him, in effect, to the status of a private citizen. Even her closest family were not to be allowed to undermine all she had done to protect and preserve the monarchy.

The remarkable success of her 2022 Platinum Jubilee was a sign of just how much she had retained the affections of her people; a particularly well-received highlight was a charming cameo performance showing her having tea with the children’s television character, Paddington Bear.

Apart from in dreams, in which she was often popularly supposed to appear, the Queen’s most regular contact with her subjects was in her annual Christmas message on television and radio. This not only reflected her work and engagements over the previous year, but it reaffirmed, with greater frankness and clarity than many of her ministers seemed able to summon, her deeply held Christian faith.

As head of the Church of England she was herself a Christian leader and she never forgot it. The Christmas message adapted over the years to new technology, but it was unchanging in style and content, reflecting the monarchy as she shaped it.

Under Elizabeth II, the British monarchy survived by changing its outward appearance without changing its public role. Republican critics of monarchy had long given up demanding its immediate abolition and accepted that the Queen’s personal popularity rendered their aim impracticable while she was still alive.

Elizabeth II, whose 70-year reign makes her the longest reigning monarch in British history, leaves her successor with a sort of British monarchical republic, in which the proportions of its ingredients of mystique, ceremony, populism and openness have been constantly changed in order to keep it essentially the same. It has long been acknowledged by political leaders and commentators all over the world that the Queen handled her often difficult and delicate constitutional role with grace and remarkable, even formidable, political skill.

Her wisdom and unceasing sense of duty meant she was widely viewed with a combination of respect, esteem, awe and affection, which transcended nations, classes and generations. She was immensely proud of Britain and its people, yet in the end she belonged to the world, and the world will mourn her passing.

![]()

Sean Lang is Senior Lecturer in History at Anglia Ruskin University.

Foresee says

On a familial scale the death of a mother is tragic for the family, but on a global scale the British hanging on to the monarchy is like the United States hanging on to the Confederacy.