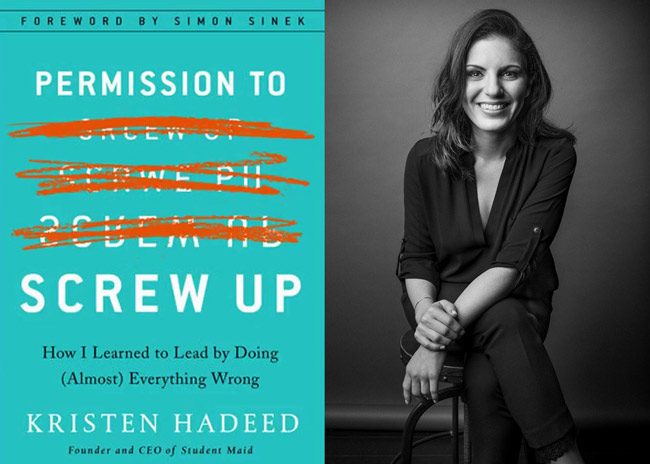

Kristen Hadeed is a 2006 graduate of Flagler Palm Coast High School, a 2010 graduate of the University of Florida, and the CEO of Student Maid, the company she founded in Gainesville. “Permission To Screw Up: How I Learned to Lead by Doing (Almost) Everything Wrong” (Portfolio/Penguin, 252 pp., $27, also available in electronic and audio formats) is her first book. Here’s a review by FlaglerLive Editor Pierre Tristam.

![]()

Kristen Hadeed isn’t kidding when she tells us in Permission To Screw Up, her deeply revealing, weirdly engrossing first book–it’s as much about scrubbing toilets as cleaning up one’s act–that building up her Gainesville-based cleaning company was “all thanks to the extraordinary amount of screwing up I’ve done over the years.”

This is someone some of you knew as a classmate or student at Flagler Palm Coast High School about a decade ago. You know the story ends well otherwise she wouldn’t be getting published at 29 by one of the nation’s leading imprints. But before you get to the pride part, it gets a little rough. Brace yourself. It’s a painful list.

In her company’s early days 45 of her 60 employees walked out on her one afternoon after slaving over other people’s scum in tropical heat while she pampered herself to salad and Facebook scrolls in a clubhouse. She had no idea why at first. (You can hear her narrate that part here.) She spent 10 percent of her first business loan in one night’s binge on sushi and booze. Ignoring her father’s advice–something the highest officials in Flagler County long ago learned they could do only at their peril: her father is County Attorney Al Hadeed–she didn’t verify whether the name of her company didn’t infringe on somebody’s trademark. It did. She blew another chunk of the loan on the mistake before settling for Student Maid Inc., a company that hires student employees almost exclusively.

That spawned its own kind of problems Hadeed wasn’t prepared for. An intern made a $40,000 payroll mistake that could have ruined the company. Hadeed threw and attended “wild parties” with her own employees, once getting held upside down by the legs above a beer keg as she drank. She called her employees “homies.” They called her “Hot Wheels,” not because of her looks, which would accelerate the rise of any neighboring mercury, but because she was an electronic office on wheels.

That spawned its own kind of problems Hadeed wasn’t prepared for. An intern made a $40,000 payroll mistake that could have ruined the company. Hadeed threw and attended “wild parties” with her own employees, once getting held upside down by the legs above a beer keg as she drank. She called her employees “homies.” They called her “Hot Wheels,” not because of her looks, which would accelerate the rise of any neighboring mercury, but because she was an electronic office on wheels.

Speaking of mercury, when she asked a job applicant during an interview what his biggest weakness was, the creep said, “you.” It’s relieving to read that she didn’t hesitate to throw him out on threat of calling the cops because another recurring theme of this book, cringe-inducing at times, is her pathological insistence on “avoiding confrontation like the plague,” in her words. She knowingly let an employee fabricate work hours until her refusal to confront the employee almost demolished her relationship with her business partner. She ignored another employee’s substance-abuse-induced latenesses and absences from work, again losing co-workers’ respect. She despised her own Human Resources handbook so she ignored it, undermining her leadership team’s authority and sowing confusion in the organization. She’d go so far as to clean up after her own employees rather than tell them they did a poor job on some assignments. She didn’t pay much attention to the leaders she assigned to branch out in Pensacola, forcing Student Maid to withdraw from its first and only chance at expansion beyond Gainesville. “Rules? Structure? Not really my cup of tea,” she writes, a blitheness that would cost her.

| From Kristen Hadeed's "Permission To Screw Up: How I Learned to Lead by Doing (Almost) Everything Wrong" (Portfolio/Penguin, 2017): "Fear kept me from giving up on Kayla.  Not just fear of what it would do to her but fear of what it would say about me. If I kicked her off the team, wouldn't that mean I too had failed? Failed to help, after I'd made helping her and the rest of our students one of my biggest priorities? I couldn't face music like that. So I held on and I held on and held on-and I failed anyway: I prevented Kayla from getting the real help she needed, and I took about fifty steps backward in the relationship I had worked so hard to build with Abby. Not just fear of what it would do to her but fear of what it would say about me. If I kicked her off the team, wouldn't that mean I too had failed? Failed to help, after I'd made helping her and the rest of our students one of my biggest priorities? I couldn't face music like that. So I held on and I held on and held on-and I failed anyway: I prevented Kayla from getting the real help she needed, and I took about fifty steps backward in the relationship I had worked so hard to build with Abby.I wish I could say that after Kayla left Student Maid, saying good-bye got easier. It didn't. And I wish I could say that Abby and I agreed on every good-bye in our company after that. We didn't. The Kayla situation was extreme. But in general, when it came to making decisions about good people who just kept messing up, Abby always took the practical approach and drew a line in the sand. I always took the emotional one and drew a line ... in the shape of a heart ... with glitter glue." |

Hadeed’s sustained wit may be to blame for this, but there’s a point where you’re not exactly sure whether you’re reading a business how-to book or a the script to the millennial sequel of “Animal House.” Or the memoirs of Rebecca Howe.

And yet she somehow managed despite the screw-ups to turn a sophomore-year start-up into a thriving company whose CEO is now so sought-after for her counter-intuitive advice and philosophy of leadership that she spends more time on the speaker circuit or advising other companies than she does in Gainesville. The book is another milestone. That she managed the feat might suggest the sort of miracle right out of Norman Vincent Peale’s supernatural inebriations of “positive thinking.”

Thankfully it’s anything but, which is why, to Hadeed’s credit, you won’t find Peale’s Power of Positive Thinking in her recommended readings, but you will find Brené Brown’s Power of Vulnerability. It’s a telling difference to understand the intellectual bracing of Hadeed’s evolution as a company leader: She’s not interested in the ethereal, undefinable rhetorical narcotic of Peale-like motivation. She grasps halfway through her Odyssean decade that motivation is a finely calibrated means to an end rather than, as so many schools, so many atrocious workplace posters and crackpot speakers have it, an end in itself. “It’s like the whole Participation Generation thing,” she writes: “if we tell people they are awesome at everything, how will they know what they are really good at?”

She begins and ends from a level as concrete–or porcelain–as it gets: not only how to convince young, largely sheltered middle to upper middle class students to clean the shit off toilet rims, but to like it. Or at least to love working for Student Maid. The company’s culture is the attraction. “How do you want to feel when you leave work,” she’d asked her leadership team at one of the monthly workshops she organized just to talk about ways to improve the company. “Accepted,” came one answer. “Listened to.” “Significant.” “Supported.” “Empowered.” “Safe.” Not exactly chimes to bottom-line shareholder suck-ups, but that’s not what Hadeed wants to be.

Money concerns, getting rich, getting ahead, the materialistic and frankly crass DNA of so many business books (some of which she cites on her list) is nowhere in Permission To Screw Up. By the time you read lines like “I didn’t care about money; I cared about Rachel and Sara,” her employees, you’ve learned that the sincerity isn’t a put-on but a mission, nor is this a get-rich-scheme book but an introspection into how to make the workplace more livable and enjoyable, a place where workers aren’t “terrified” to be (Hadeed was desolate to discover that one of her workers was), and where “our philosophy of learning by screwing up” isn’t a slogan but part of “one overarching philosophy: If someone’s good qualities outweigh the bad, we will fight for that person.”

Hadeed is exhibit A, but the book curates a few other exhibits, managing at times to do what I thought would be the impossible in this sort of business-minded work: move you to tears with the story of one particular employee’s eventual firing, the substance-abusing one who ended up in rehab and a rebuilt life thanks to the firing, the older, irascible invalid rejuvenated by her interactions with her student maid, or the story of Hadeed’s mother’s humbler beginnings, which her daughter hears for the first time during a meeting with her directors after her mother had joined the leadership team. Or Hadeed’s own story of how she got the cleaning bug.

This St. Augustine-in-the-garden sort of transition from paralysis to decision is the more remarkable for having been that of a 10 year old, and for becoming the template of her business model: she’s running a company primarily to make the people who work for her happy to be doing so. And to not fear getting fired.

The confessional passage and many like it place the book firmly in that uniquely American tradition, “an entrepreneurial journey,” in her words, that is almost indistinguishable in form and tenor from the bildungsroman–a story of formative development with self-improvement as the eternal goal. But it remains grounded in the grime and stumbles of the everyday. The book’s seven chapters, each developing its own arc from crisis to resolution, are written in an earnest and breezy style without hints of presumption and, given the genre, an impressively limited number of business-memoir clichés (“I trusted her with every bone in my body,” “bursting at the seams,” “pulling the trigger”). In a brief email exchange we had she made the two and a half years it took her to write the book sound like agony. If so, it never shows. In a genre so rich in bores and bromides, that’s an achievement.

Intentional or not the tone of the book matures as its chapters advance and Hadeed sheds many of her more youthful personas. No more “homies,” no more parties: “Curling up with a paperback written by a successful CEO and sipping a cup of hot chai became my ideal Friday night.” The business grows, so does her compulsion for improving its interpersonal workings, a compulsion that gets quite severe, with six-hour monthly workshops devoted to those ends. She abandons what she’d called “shit sandwiches” (the favored description for dispensing constructive criticism wrapped in compliments to employees) and perks like Friday DJs for more meaningful if still gimmicky-sounding techniques. There’s the unfortunately called “FBI” — “Feeling-Behavior-Impact,” a feedback technique–the “Wow Wall,” “The Commandments,” “The Line.” That last turned, for me anyway, from an employee-bonding exercise into a scene out of The Handmaid’s Tale, as when Hadeed refers on two occasions to “values that would guard our cultural gate.” I realize that in context it has nothing to do with how the line could be read, but in today’s larger context of sinister gates, walls and bans, an editor should have pointed out the infelicitous metaphor.

Of course, she addresses monsters like me head-on:

To some people, the way we interact as a team seems way too touchy-feely, and my openness is TMI. When I talk about vulnerability and the relationship work we do at Student Maid, I always get at least one or two eye rolls. Some people say, ‘That crying crap doesn’t belong in the workplace,’ or they say we ‘sound like a bunch of hippies.’ One time a guy in the audience asked me sarcastically, ‘So you’re saying if someone’s dog dies, I’m just supposed to sit and cry with them?’

First of all, yes, you heartless monster.

Okay, I didn’t actually say that. But I wish I had. What I really told him is that being vulnerable and open and allowing people to feel at work isn’t about crying with someone. It’s about understanding what they’re going through so you can work better together.

I confess here to a mixture of grudging admiration and distaste for some of those techniques, whose ends are nothing if not well-intentioned (and certainly more honorable than techniques designed to bleed employees dry of productivity), but whose ulterior motive may diminish the genuineness of the gesture. Workplaces as reeducation camps isn’t my thing, though I’m also past the years when affirmation through colleagues means anything to me, so my prejudices cloud my vision. And in the end the sheer integrity of Hadeed’s approach wins you over anyway, not to mention the startling way she puts her money where her mission statement is: “Our students could easily keep their supplies in their cars and meet their partners in the parking lot to carpool, rarely setting foot inside our doors. But we require them to come inside because we’ve learned that if we want to encourage close bonds within our team, we have to be intentional about it and make time for people to cultivate them. It’s expensive to pay everyone in our company for an extra thirty minutes each time they work, but to us, it’s money well spent.”

From Nickel and Dimed: On (Not) Getting By in America, by Barbara Ehrenreich (Holt, 2001): "Let's talk about shit, for example. It happens, as the bumper sticker says, and it happens to a cleaning person every day. The first time I encountered a shit-stained toilet as a maid, I was shocked by the sense of unwanted intimacy. A few hours ago, some well-fed butt was straining away on this toilet seat, and now here I am wiping up after it. For those who have never cleaned a really dirty toilet, I should ex~lain that there are three kinds of shit stains. There are remnants oflandslides running down the inside of toilet bowls. There are the splash-back remains on the underside of toilet seats. And, perhaps most repulsively, there's sometimes a crust of brown on the rim of a toilet seat, where a turd happened to collide on its dive to the water. You don't want to know this? Well, it's not something I would have chosen to dwell on myself, but the different kinds of stains require different cleaning approaches. One prefers those that are interior to the toilet bowl, since they can be attacked by brush, which is a kind of action-at-a-distance weapon. And one dreads the crusts on the seats, especially when they require the intervention of a Dobie as well as a rag. "Let's talk about shit, for example. It happens, as the bumper sticker says, and it happens to a cleaning person every day. The first time I encountered a shit-stained toilet as a maid, I was shocked by the sense of unwanted intimacy. A few hours ago, some well-fed butt was straining away on this toilet seat, and now here I am wiping up after it. For those who have never cleaned a really dirty toilet, I should ex~lain that there are three kinds of shit stains. There are remnants oflandslides running down the inside of toilet bowls. There are the splash-back remains on the underside of toilet seats. And, perhaps most repulsively, there's sometimes a crust of brown on the rim of a toilet seat, where a turd happened to collide on its dive to the water. You don't want to know this? Well, it's not something I would have chosen to dwell on myself, but the different kinds of stains require different cleaning approaches. One prefers those that are interior to the toilet bowl, since they can be attacked by brush, which is a kind of action-at-a-distance weapon. And one dreads the crusts on the seats, especially when they require the intervention of a Dobie as well as a rag. Or we might talk about that other great nemesis of the bathroom cleaner-pubic hair. I don't know what it is about the American upper class, but they seem to be shedding their pubic hair at an alarming rate. You find it in quantity in shower stalls, bathtubs, Jacuzzis, drains, and even, unaccountably, in sinks. Once I spent fifteen minutes crouching in a huge fourperson Jacuzzi, maddened by the effort of finding the dark little coils camouflaged against the eggplant-colored ceramic background but fascinated by the image of the pubes of the economic elite, which must by this time be completely bald." |

Imagine that. We live in a work culture that routinely, brazenly abuses millions of hourly workers’ time by not letting them clock in before they have their work gear on and half their prep work done, which is corporate thievery pure and simple, and here’s a CEO paying her employees extra to hang out. Wall Street would be apoplectic. So I don’t care what gimmickry she uses: the fact that she puts her philosophy to work to that degree suggests a humaneness often alien to the contemporary workplace.

The self-deprecating brightness of Hadeed’s prose and the mixture of affection and self-improvement she projects on her employees can make you forget that Student Maid is still very much part of an enormous and bleak job sector, the world of the hourly, low-paid, overstressed worker. It’s an indispensable part of America’s work culture. But it’s largely unseen, its millions of workers the Ellisonian invisibles of our consumer-entertainment complex. Barbara Ehrenreich in Nickel and Dimed and David Shipler in The Working Poor exposed that world from within a decade and a half ago with depressing clarity, to no discernible effect. Ehrenrich went undercover as a minimum-wage worker in the grimiest trades, including as a maid, to see what it takes to make it at that end of the wage scale. Her one-page description of her encounters with filthy toilets–“I should explain that there are three kinds of shit stains…”–is a Melvillian sanctus to scatology. Permission To Screw Up’s descriptions regrettably never reach toilet seats’ undersides, but Ehrenreich and Hadeed nevertheless intersect in one essential regard: “I can put up with shit and snot and every other gross substance I encounter in this line of work,” Ehrenreich wrote, words that could be the ideal epigraph to Hadeed’s book. “The only thing I’m squeamish about is human pain.”

Shipler’s and Ehrenreich’s books were chronicles of indignities that are inseparable from workers’ conditions. Those workers are either at the receiving end of their employer’s indifference or their customers’ contempt. It is when Hadeed writes of nurturing the dignity and pride of her workers, when she writes of leading “with compassion and humility” and of building confidence out of failure that her book soars, taking the reader’s hopes with it. It doesn’t have to be that way, she tells you again and again: “When we bring our humanity to work, so do our people.” But she is the exception, if also maybe a scout and trendsetter of a new generation of service-company leaders.

I hope you’ll agree by now that there’s no condescending to this millennial about hers or her generation’s work ethic. If millennials are so often (and to me, so stupidly) scorned and ridiculed, perhaps it’s because they’re not big on the casual workplace brutalities their elders take for granted, whether as bosses or subservient employees. Where employers see young employees who supposedly refuse to be led or follow orders, maybe what their barnacled vision isn’t letting them see are employees who see being trusted and respected as a prerequisite for their time. It’s precisely what Hadeed’s philosophy emphasizes, seemingly with great success. It’s about time. Millennials don’t need a reality check. Their elders do.

Megyn Kelly’s cue-card interview of Hadeed on her Oct. 20 show reflected the false assumptions. All Kelly could focus on was the myth of the “cupcake” or “snowflake” generation her former network did so much to manufacture, blind to the irony that those who moan about millennials are the same, crustier geezers once ridiculed as the stoned and self-absorbed children of Charles Reich’s Greening of America. The book goes to some lengths to correct the armchair generalities. Sure Hadeed dealt with her share of absurdities–the questions about whether to mop a floor again if it still looked dirty or what to do if the water from the tap feels too hot or if a house alarm was triggered by mistake. But a certain lack of common sense is more universal than generational. Job-training programs are populated by the middle-aged, not the young. And most of life is, as Woody Allen put it, about showing up and learning–which these students do far more than not. The entitled aren’t college students but their elders who are the overwhelming, disproportionate beneficiaries of government benefits. Hadeed’s students are working for a reason: like her, their parents may be comfortable, but the students themselves need to make ends meet. (And a 3.5 GPA or better is a requirement for the job at Student Maid).

From Kristen Hadeed's "Permission To Screw Up: How I Learned to Lead by Doing (Almost) Everything Wrong" (Portfolio/Penguin, 2017):  “I’d admit that there’s no guide that explains exactly what it’s like to lead and that no one gets it right the first time. You don’t mess up a couple times and then skip your way to success. You mess up, get a little closer to achieving something, and then make another mistake that puts you steps back again. Sometimes you make the same mistake twice. Sometimes you feel like you want to give up. Sometimes you go to bed crying. These are the things I wish someone had told me when I was first starting out. They’re things I wish more leaders would get comfortable acknowledging. Because let’s face it, leadership is really, really hard. And I’ve learned that if it’s not hard, chances are you’re doing it right. “I’d admit that there’s no guide that explains exactly what it’s like to lead and that no one gets it right the first time. You don’t mess up a couple times and then skip your way to success. You mess up, get a little closer to achieving something, and then make another mistake that puts you steps back again. Sometimes you make the same mistake twice. Sometimes you feel like you want to give up. Sometimes you go to bed crying. These are the things I wish someone had told me when I was first starting out. They’re things I wish more leaders would get comfortable acknowledging. Because let’s face it, leadership is really, really hard. And I’ve learned that if it’s not hard, chances are you’re doing it right. Let me sing this from the rooftops: I am not infallible, and my company is not a utopia. In fact, sometimes we're both kind of a mess. Those dark circles under my eyes? They're pretty much permanent. At Student Maid, despite all we've learned and how far we've come, we still get it wrong. But we will never shy away from admitting that, because getting it wrong is what helps us get it right." |

The book does have its flaws. For a business book, even one cast as a business memoir, it is sorely lacking in numbers. We never learn how many employees typically work for Student Maid beyond the “hundreds” who have cycled through over the decade. We see the leadership team grow but have no sense of the company’s actual growth, no dollar figures that could give us a sense of a year’s volume, no idea whether employees get benefits (we do know they’re paid minimum wage or a little more), what the mean number of hours happens to be for employees, what the actual turnover happens to be in an industry with an average turnover of 75 percent, and so on. Even the timeline of Student Maid’s evolution is vague. That’s not trivia: it’s central to the thesis, as are other curious questions that go unanswered along the way–how the company’s hiring norms square with equal opportunity laws, how she might have turned down the desperate single-parent of several children for a job, why the model isn’t being replicated beyond Gainesville, what sort of responses other CEOs give when presented with the Student Maid model or whether it’s being adopted by other companies. Hadeed meets with enough fellow-CEOs to know.

And for all of Hadeed’s focus on “becoming more forthcoming about personal situations that affect them at work,” we read not a word about Hadeed’s own personal situation beyond work’s walls. Her father looms from Olympus in the first third of the book, her mother joins the leadership team in the last third, her sister makes a cameo, but that’s about it. For someone who hosted keggers and manages to be the life of the party and the workplace, the silence stands out and begs the question: does her style of leadership require complete surrender to work? That would be a disheartening contradiction as it would mean that to provide the right balance between work and decent lives outside of work for others, a CEO must deny that balance for herself, though Facebook gleans suggest she is no social anchorite. The silence could also be the symptom of a privacy-control freak (I entirely sympathize), or the subject of Hadeed’s next book. It’d be worth the wait.

Until then, Permission To Screw Up is an admirable corrective to the business world’s male-centric myth of macho infallibility. That world and its porn-rivaling glossies loves to present its stars as the retouched centerfolds of entrepreneurial supremacy. Hadeed is here to tell you it’s a bit more shit-stained than that, and that’s OK. It was her mission, she writes, “to make Student Maid a place where people had room to screw up and to figure things out on their own without having to worry about losing their jobs in the process. I figured that if I succeeded, it would be a win for all of us: Our students would gain problem-solving skills that would help them thrive not only in their jobs at Student Maid but also in their future pursuits; they would learn to trust themselves and become more independent; and they’d be able to take pride in their accomplishments.” She succeeded.

And if this book doesn’t stand out as it should, I suspect it’ll be because it’s more far-seeing than workplace arbiters are comfortable with. I don’t imagine it’ll be permissible reading at Wal-Mart employee retreats and restaurant association conferences in Vegas. But it should be required reading for anyone who presumes to lead employees, whatever the size of the organization, the division or the ambition.

![]()

Paula says

Love it! Congrats, Kristen!

Terminus says

Meh, not impressed. Good on her for getting this published but I gained more insight from a fortune cookie.

Chris A Pickett says

Don’t forget to have fun at work. I reckon I had fun at work in the military while I was off in the Jungle, or maybe when I was aboard a fishing or research vessel offshore for weeks at a time. Work is not supposed to be fun, that is why they call it work. The problem is MOST of these young people these days have no concept of work. Show up right at start time-NEVER early, maybe 10-15 minutes late…oh well. Not feeling to good about myself today, call in sick. Sit on their cell phones quite a bit while at work. Cannot talk to people directly. Used to be if you weren’t there half hour to 15 minutes early you were LATE. Now they wake up 5 minutes before they have to leave, throw on some pajamas, sweats or “leggings” and they’re ready for “fun”……….

fredrick says

Pierre, Hopefully it will help you with handling your staff of 350 at Flagler Live. They are an unruly bunch and require leadership and direction.

Pierre Tristam says

Fredrick, that’s a staff of 600, my good man (those big layoffs are still in the future), and yes, I could learn a thing or two from Permission.

Pogo says

@Chris A Pickett

Your Fox & Friends view of young people says more about you than them. Meanwhile, it’s a perfect description of the lazy infantile gluttonous slob Trump; the swaggering draft dodging racist spray tanned monster, tweeting twit, and self described sexual predator. Or as Fox & Friends would say – daddy!

Anonymous says

Why don’t people like this just get a job and work for a living rather than run around trying to convince us how great they are? I guess the proof is in the pudding….there is no doubt down the road we are going to read another publicity stunt by this young lady. SMH

Lindsey says

Terminus – Where’s your book?…I’m dying to read about how you never screw up and make life choices based on fortune cookies.

Chris – I’ve been in the military for 9 years and when it’s time to work you work and sometimes work allows you to have a little fun. Being on a boat for an extended period of time can be very fun as well, some of my best memories were on a ship (working and having fun). Sounds like you have some personal experiences with younger people and aren’t acknowledging that this author spent the better half of her FREE time writing and publishing a book. Good on her for getting out of bed early, smiling at work, and getting published at 29.

Anonymous – I’m pretty sure her job was starting a company and watching it fail then succeed and learning from her experiences. My favorite part about your comment is that you act like you were forced to read her book when you haven’t even read the article. What proof is in the pudding? What’s the publicity stunt? I’m pretty sure she’s not a Kardashian, but jealously does make people talk kinda crazy. Good look out there!