Note: this is an account of the Paul Miller trial’s closing session on Friday, before the verdict was delivered in early afternoon. For the account of the verdict, go here.

Paul Miller was not scared when he killed his neighbor Dana Mulhall the evening of March 14, 2012. He had not been in fear for two months. He was not incapable of avoiding a confrontation. Rather, Assistant State Attorney Jacquelyn Roys said in her closing arguments in Miller’s murder trial Friday morning, Miller had revenge on his mind. He and Mulhall had been in an argument two months earlier. Mulhall had been rude to Miller’s wife. “It didn’t start in reality. It started building in Paul Miller. How dare you say those things in front of my wife, how dare you talk to my wife that way.”

That, Roys said, is what led to Mulhall’s murder. “Mr Miller had been building this for months. It was not about fear. It was about revenge,” she said.

Not so, the defense countered in its closing arguments. Miller “did not shoot him out of anger,” defense attorney Carine Jarosz said. “He shot him out of fear. If anybody lost their cool in this matter, if anybody was enraged, it was Mr. Mulhall.” A Mullhall enraged by two barking dogs, a Mulhall drunk and emotionally affected by alcohol. A Mulhall who put Miller in fear of his life. “He had his adrenaline pumping and the alcohol fueling his emotions,” Jarosz said, referring to Mulhall’s drunkenness with the compulsiveness of a drinker going back to the drink, and painting the image of a man so irrational that he never weighed the consequence of claiming that he had a gun—the claim (never proven in court) that led Miller to pull his own gun from behind his back and shoot him five times.

And so it went as the two sides over 90 minutes Friday morning finished their case before a jury of three men and three women (all white), ending the week-long case before the judge read long instructions to the juries before the six were cloistered in a room to decide Miller’s fate. There is no telling how long the jury may take. There is no limit on how long it may take to complete its deliberations.

The jury may find Miller guilty of second degree murder, it may find him guilty of manslaughter, or it may find him not guilty by reason of having acted in self-defense. The verdict must be unanimous. The judge read extensive instructions on how the jury may reach its verdict. Within those instructions, which the jury is lawfully required to follow to the letter, subjectivity is severely constrained, but certainly not eliminated. For example, one such instruction will constrain the self-defense claim if the jury finds that if Miller, after he armed himself, “renewed his difficulty with Dana Mulhall when he could have avoided the difficulty.” That was one of the prosecution’s central themes: at no point did Miller seek to avoid the “difficulty,” but rather sought it out.

The jury, which was required to leave its cell phones or any other electronic device in the courtroom while it deliberated in the jury room, began its deliberations at 11:25 a.m.

The prosecution’s Jacquelyn Roys presented closing arguments first.

Yes, there was an argument that March evening. Yes, Mulhall was yelling. He’d been yelling at the dogs, because the dogs were barking. “He is not yelling at anybody,” Roys said, the nine jurors (including the three alternates) riveted to her unabashedly theatrical recreation of the fatal confrontation. “He is yelling at dogs. They’re over there barking. He’s allowed to do that.”

But it was Miller, she said, who provoked the situation and raised it from a man yelling at dogs into a hateful face to face confrontation, then a murder. Miller did so when he chose to walk out of his house. “He provoked the situation,” Roys said. “Simply put, he walked out, he confronted him, barked orders at him, and that’s what started it.”

Mulhall had been shaking the fence. But he stopped doing so when Miller told him to. “Dana Mulhall was an obese man. You heard his stature and weight. He wasn’t climbing over anything. He was standing at the fence, yelling,” Roys said. “He didn’t come for a gunfight. He wasn’t armed. He was not prepared for this man full of hate to take his life that day. Never saw it coming, because it is not reasonable.”

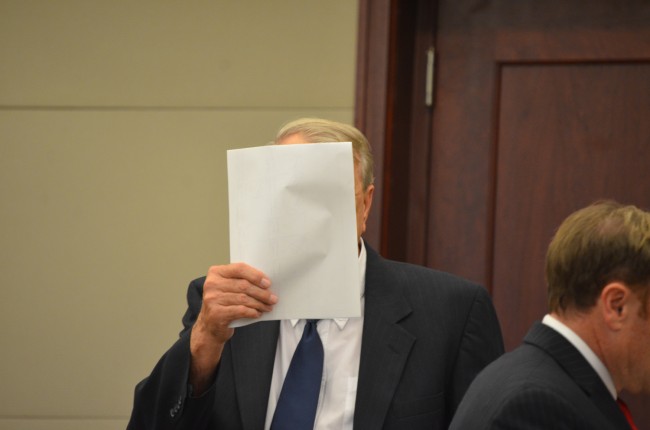

Roys played the 911 call Miller placed after the shooting, with those words–”I shot his fucking ass”–again filling the courtroom (as Miller, at the defense table, pursed his lips) and Roys pointed to the computer playing the recording to say, when Miller claimed he was being threatened, that Miller didn’t say Mulhall had a gun. And then the hang-up.

“Indifference. That was right after he shot the man, remember?” Roys said. “That’s anger: ‘I shot the son-of-a-bitch.’ ‘He’s begging for it.’ ‘I shot his fucking ass.’” Where is the fear then, Roys asked? “How are you so cavalier at this point, for yourself, forget the fact that you just shot this man to death.” Instead, Miller left his gun on the porch, loaded, “in the path where this man has to come to get to his house.” How does he know he’s out of danger? “You know how he knows? He knows because he was never in danger,” Roys said.

“That’s a man who is absolutely 100 percent in charge,” Roys said, then comparing Miller’s behavior that fatal day to his behavior on the stand on Wednesday—a man who will not be challenged, a man who will insult, condescend, refuse to answer questions, and call anyone who questions him “rude.”

“What happens when he’s outside, when he’s on his own property? ‘You’re not going to mess with me.’ It’s not fear,” Roys said. It’s control.

Roys agreed with the defense’s claim—made in the defense’s opening argument—that “reasonable” was the word of the day. But she argued there was no such reasonableness in play that day: Miller could not reasonably believe that he was in fatal danger. “You can’t go rattle the cages and then say, eh, I got bit. It doesn’t work that way.” According to Miller, Mulhall was 10 or 12 feet away. There never was physical contact. A reasonably cautious and prudent person must believe that the only thing to do under the same circumstances is to confront and shoot Mulhall, for the self-defense claim to hold up, Roys insisted, reading from the jury instructions Circuit Judge J. David Walsh was soon to read himself.

The crux of Roys’s argument was that Miller, not Mulhall, initiated the fatal confrontation, even if Mulhall initiated the yelling. She had discounted the yelling as itself being a trigger, since anyone is Roys claims entitled to yell from his or her property. She highlighted, again and again, Miller coming out armed, after his deliberate walk deep into his house to retrieve the 9 mm gun rather than—if he felt in danger—call 911. There never was a claim by anyone, including Miller, that Mulhall was charging him, or about to climb the fence, with one exception: the pathologist the defense hired to interpret Mulhall’s autopsy. “Where did he get that information?” Roys asked pointedly, since there was little in the report that could have led to a claim of climbing. “Oh, that’s right, he was a paid witness,” Roys said dismissively. The only witnesses to the confrontation’s earliest stages—three boys walking down the street—never say the fence-shaking, or Mulhall’s charging.

It was then the defense’s turn.

“Paul told you when he testified that he has an eighth grade education,” Jarosz, the defense attorney, said as she opened her closing arguments, contrasting Miller’s lack of sophistication with the more polished approach of the lawyers and other professionals who have been central to the case. (Co-counsel Doug Williams sat to the left of Miller, looking on as Jarosz made the arguments.)

Jarosz then related the events leading to the killing, starting with the January incident all the way to “the split second” decision to pull out his gun and shoot. “A lot has been made of the fact that he shot five times, that he shot as Mr. Mulhall was running away.” But he did so “until he thought the threat was gone,” because Miller was fearful that Mulhall would pull his own gun and shoot him (a gun Mulhall did not have).

Jarosz noted that Mulhall was 30 pounds heavier and 13 years younger than Paul. (In fact, when Miller was booked at the Flagler County jail, his weight was listed as 220 pounds, just 10 pounds lighter than Mulhall. Miller is also three inches taller.)

And she insistently noted Miller’s cooperativeness and consistency throughout: He never fled, he never hid, he never hid the evidence, he’s been honest,” Jarosz said. Nor did he “create the self-defense argument over the last month.” Rather, “he’s remained consistent because he is telling the truth.”

The prosecution did not contest that he was telling the truth so much as contest his interpretation of self-defense, however—a distinction the defense addressed by portraying Mulhall as a man enraged, drunk, his judgment badly affected by the alcohol in his system. “It’s been proven that Mr. Mulhall was enranged,” Jarosz said, remindfing the jury of the testimony of two of the boys, 11 years old at the time, who had been walking down the street at the beginning of the confrontation. One of the boys had noted that Miller showed Mulhall the finger. The other, with some uncertainty, had referred to Miller telling Mulhall to calm down, that the problem could be worked out, that children were present.

But Mulhall was drunk, unreasonable, unreasoning. If one is twice over the legal limit, she said, there is no such thing as tolerance anymore, Jarosz said. “Mr. Mulhall was intoxicated just as Mr. Miller suspected, just as he told the 911 operator.” It was not Miller who provoked the situation, but Mulhall. Miller “was reacting to Mr. Mulhall’s behavior and trying to protect himself because he thought that was necessary,” Jarosz said.

“There’s no evidence of ill will or hatred or spite. He felt that he had no other choice,” the defense attorney said of her client, concluding that the state had not proven its case of second-degree murder beyond reasonable doubt.

While Roys had used all of the square footage in front of the jury, from near the defense table and behind the dais set in the middle of the room, to the wooden rail delineating the jury’s area from the rest of the room, Jarosz remained the entire time behind the dais. It was a telling detail that summed up the two sides’ approach and personalities throughout the trial: a far more aggressive, at times indignant prosecution, especially when Roys was doing the talking. Her co-counsel Kayla Hathaway was used for more genial cross-examinations, as with children or more neutral witnesses. Between Williams and Jarosz, the latter was closer to Roys’ style than Williams, though she was more reserved with those tactics, and far more controlled—almost subdued—in her closing.

The two women’s voices were at distinctly different decibel levels—Roys’s was high, Jarosz’s was stern, but not lower. Roys used her body—her hands, her pacing, her facial expressions, head shakes. She recreated Miller’s deliberate motions through his house, she recreated, several times, Miller’s motion as he gunned down Miller, her “bang, bang, bang” sound repeatedly filling the courtroom in that deliberate slowness witnesses had described when they heard the shooting. And she recreated Mulhall’s contortions as he was shot. She rarely looked at her notes, whereas Jarosz seemed attached to them from behind the dais.

The prosecution got the very last word, after the defense finished.

Roys again went through some of the same theatrics, using the chance to discredit the defense one more time. Then she closed with the gesture of the morning, as if in an echo of the other gesture she had shown the jury moments earlier, when she brandished the finger—the finger Miller had shown Mulhall. Her last gesture was this: she walked to the side of the courtroom where all the exhibits were stashed and retrieved the large portrait of Dana Mulhall, beefy-faced and sun-drenched in his shades, and alive then, in that portrait—as alive as he could be made to be in the courtroom.

Roys held the portrait before the jury, and finished on Miller’s disdainful words to the 911 operator: “You heard it,” Roys said. “’I shot his fucking ass.’ Thank you.”

So sad says

Praying for justice. Excruciating. Please put this man away.

Alfred E. Newman says

I’d never be foul-mouthed to a woman – she can be someone’s mother, sister or wife.

It’s also not a manly, nor gentlemanly thing to do, especially to an old-schooler like me.

DON’T DO IT. Find someone bigger than you to spew venom.

I understand Mr. Miller’s simmering hatred towards his neighbor.

Mr. Mulhall made a big mistake here. And he paid with his life.

There’s a lesson to be learned here.

I do not condone shooting someone over this, much less in the back.

A knuckle sandwich would have sufficed. Even if Mr. Mulhall had kicked the

older Mr. Miller’s behind – Mr. Miller would have been seen as a stand-up guy and the winner.

A man can’t be afraid to take some lumps in the defense of his wife’s honor.

Why do men need guns to settle quarrels for everything now?

ryan says

It isn’t murder if it is self-defense, and this was not self defense.