Palm Coast’s attorney today prepared the city council for changes ahead to the sign ordinance, “something that is highly emotional and highly controversial in the first place, which is the regulation of signage, political, commercial, residential, free speech, all of that,” Bill Reischmann told the council. “Something that’s near and dear to everyone’s hearts.”

Those changes are going to require the city to be more permissive, not more restrictive, with signs, including political signs and especially temporary signs that have to do with garage sales, open houses, real estate sales, church services and the like—as long as the signs aren’t implanted on public land or rights of way. There, nothing will change in the city’s ban on almost all temporary signs.

The reason for the coming changes: in mid-June, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled unanimously that a city’s code enforcement regulations may not be determined by the content of signs in any way, and may not categorize such signs based on content.

“The decision that the Supreme Court made affects not just the city of Palm Coast, although it doesn’t affect us that much,” Reischmann cautioned, “but it affects every city in the United States of America because every city in the United States of America regulates signs, and this Supreme Court case said a lot about how cities can regulate signs.”

So Palm Coast’s attorney and the city’s code enforcement and planning divisions are starting a review of the ordinances that pertain to signs to ensure that Palm Coast is in compliance. In the weeks ahead, the council will very likely have to discuss and adopt proposed changes if it’s to avoid litigation.

“If this council, along with any other city council or city commission in the United States of America want to be extremely conservative in how to react to the Supreme Court case, you’re going to have to make changes,” Reischmann said. “Everybody is going to have to make changes in how they regulate temporary signs. And the conclusion we reached last week is that that’s not going to be a popular discussion because you’re going to have to avoid looking at common sense. You’re going to have to throw that away.”

Reischmann referred to a concurring opinion in the Supreme Court decision by Justice Elena Kagan who, even though she joined her eight colleagues in the judgment—and only ion the judgment—excoriated her colleagues for the broadness of the ruling. She agreed that the code regulations at issue in Gilbert, Ariz., did not pass “even the laugh test,” but disagreed with making those regulations the standard for the court’s new approach, which essentially throws out innumerable “common sense” code regulations on the books across the nation today. “As the years go by, courts will discover that thousands of towns have such ordinances, many of them ‘entirely reasonable,’ Kagan wrote, citing the case’s oral arguments. “And as the challenges to them mount, courts will have to invalidate one after the other. (This Court may soon find itself a veritable Supreme Board of Sign Review.) And courts will strike down those democratically enacted local laws even though no one—certainly not the majority—has ever explained why the vindication of First Amendment values requires that result.”

Nevertheless, the ruling stands: Kagan merely predicted the sort of challenges cities like Palm Coast now face, balancing what they consider to be existing, reasonable regulations with compliance with a new Supreme Court standard.

Palm Coast may have to scrap common sense regulations of temporary signs to abide by a much more permissive standard that may elevate First Amendment rights above aesthetics.

“We want to try and continue to protect the integrity of our sign code and what it represents,” Reischmann said, “which is trying to preserve the esthetics for the citizens of Palm Coast as well as preserving the safety for folks that are pedestrians and motorists in the city as far as the clutter that comes with the different types of signs. We’re going to try to maintain that. But also live by the letter and the spirit of this very recent case so we don’t have situation where we’re incurring additional costs for the taxpayer where we’re defending something we can’t defend.”

Don’t get too excited about right-of-way and public land signage. Nothing will change there. “We’re talking about signs on private property not on public rights of way, because what you hear about the most are the signs on public rights of way, the garage signs, the realtors’ signs etcetera,” City Manager Jim Landon said. If anything, the court’s ruling reaffirms Palm Coast’s long-standing rule: no signs at all in rights of way, because if you allow one kind of sign, you must allow them all. And Palm Coast won’t, otherwise its code enforcement officers would have to be in a position to have to read a sign to determine whether it’s in compliance or not. And the moment they must do so, under the court’s new order, then they’re exercising a content judgment afoul of the First Amendment.

Landon reassured council members about what signs residents can place in their front yards, a standard entirely different from public lands. “You can do that today. Just like, you can put vote for so and so, open house, puppies for sale, whatever,” Landon said. “And that is allowed in your front yard, with certain conditions, but those conditions have nothing to do with what it says. It may be the size, those types of things. But we can’t look at it and say, no no, puppies for sale isn’t OK, house for sale is OK, because at that point we’ve read it to determine whether or not it’s OK. If you put a sign out that’s 500 square feet, then we can say no, you can say whatever you want on that, but it has to be a certain size.”

The Supreme Court case was the end result of litigation going back to the town of Gilbert, Arizona, population 230,000. Gilbert’s code prohibited the display of outdoor signs anywhere in town without a permit. But it also exempted 23 categories from the permitting requirement. It defined each category. Three such definitions included “ideological” signs, which included signs relating to political events, garage sales and special events. Those signs were given the most latitude. They could be up to 20 square feet and placed in all zoning districts without limits. “Political signs” formed another category. Those were treated les favorably. They could be up to 16 square feet on residential property and up to 32 square feet on non-residential 32 square feet on non-residential property, including rights of way. But they were limited to 60 days before and 15 days after an election.

The third and most restricted category was “directional signs” that pointed people to a church service, non-profit or educational gatherings or meetings, and so on. Those could be no larger than 6 square feet and they could be on rights of way and public property, but no more than four signs by the same organization could be on any single property, and they were limited to 12 hours before an event and had to be removed within an hour.

Rev. Clyde Reed of Good News Community Church had no building of his own for his services. He held them at two elementary schools and other locations in or near town. He’d place 15 to 20 signs around town, often in rights of way. The signs would be removed by noon. Twice he was cited by the city’s code enforcement department for violating the city’s sign ordinance, once for exceeding the time limit, another time for also failing to include the date and time of the event. City officials actually confiscated his signs, forcing him to retrieve them from municipal offices. Reed tried to reach a compromise with the city. He was rebuffed. The town’s code compliance manager told him there would be “no leniency under the code” and promise further punishment of any violations.

Reed sued in district court, arguing through his attorney that the sign ordinance violated his freedom of speech and his 14th Amendment right to equal treatment. But he lost. He appealed to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals. He lost there, too. The city’s regulations of signs were deemed “content neutral,” meaning that the city was not regulating the content of signs, but rather their display based on what category of content they fell in.

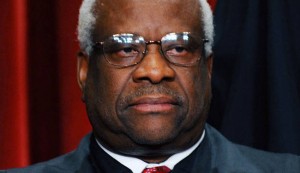

That’s the distinction the U.S.; Supreme Court didn’t buy into, and called the code itself anything but content neutral, since it established categories based on content. It did not matter that the town of Gilbert’s regulations were “innocuous,” that they did not made distinctions based on ideas or subjectivity. What mattered to the Supreme Court was that it was categorizing signs based on content, however innocently and for whatever good purpose. “The town’s sign code is content-based on its face,” Justice Clarence Thomas wrote for the majority of a unanimous decision. It defines each sign based on the city’s categorical determinations “then subjects each of these categories to different restrictions.”

Once that’s established, the ordinance must then fall under “strict scrutiny” for constitutional validity. And once the court did that, it found the ordinance unconstitutional.

It’s not that a government may not under any circumstance regulate speech. But if it does so, it must prove that the regulation is “narrowly tailored to serve compelling state interests,” the court ruled.

“As you can imagine in my world, you get the blogs about our garbage rates and utility rates and golf courses and things like that,” Reischmann said. “Well, in my world the blogosphere is going crazy over this case.” He then related the matter to Palm Coast. “Obviously we went and looked at all of our cities’ codes and we’re doing what we need to do to make the changes necessary. I will tell you that what everyone’s concluded from everyone I’ve talked to is that we’re going to do what we need to do to protect our cities, but we need to tell our cities that what had been fairly black and white is now less black and white. So what we’re going to do is we’re going to be conservative, we’re going to be proactive and we’re going to protect the cities from a claim that we’re violating people’s free speech rights, and the place we start with that is working with your planning department to look at your sign code, to make some changes to the findings in the preambles and look obviously very closely at the regulations of your temporary signs, but also work with your code enforcement department to make sure that they are going to code enforce signage in a way that meets the spirit if not the letter of this decision, so the city of Palm Coast does not face claims brought by churches or politicians or real estate folks or people that want to have garage sales and so on and so forth.”

![]()

Click to access supreme-court-signs.pdf

Dog gone it says

So I can put a sign on my front yard now that says:….. If you dog poops, use the scoops !

Anonymous says

I think you can do it now and was OK before??

Dennis C Rathsam says

I had a lady who lived across the st. her dog was always loose and kept leaving me presents on my front lawn. After speaking to her, she was indiferent and didnt care. One day I caught them in action, and I blew my top, I called her every name in the book, still she wouldnt pick up the do do. So I pick it up and put it in front door….Problem solved!