“Moderation in all things. Not too much life. It often lasts too long.”

–From H.L. Mencken’s Notebooks.

| Jefferson’s religion | Norwegian welfare | Emerson on Rabelais| Bare necessities | Flagler’s primary election day | Spanking Vidal | Losing AC | canoeing John Updike’s Florida lizards | Afghan indifference | Clint Eastwood’s endorsements | Flaubert’s retardation | September Notebook | Follow me on Twitter

![]()

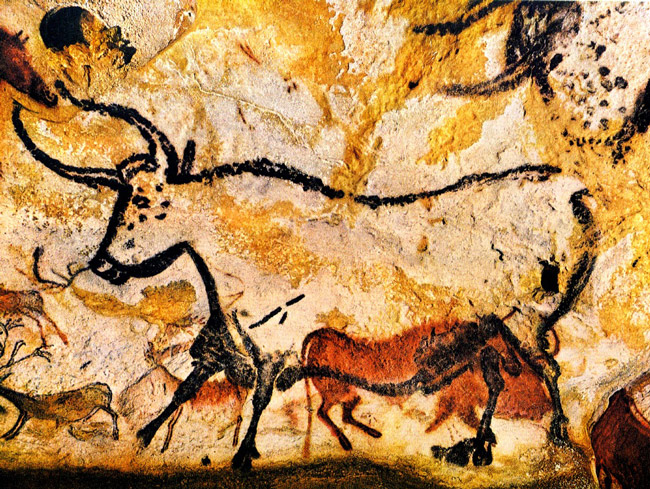

Between the tyrannies of Twitter, Facebook and texting and the reduction of roughly half American discourse to like buttons, emoticons, acronyms and “diggs,” whatever those are, the reign of the short attention span is culture’s new Caesar. On the other hand the book of hours was basically a medieval blog, and the walls of Lascaux were pre-literate notebooks, better written than most of what’s been done since. So here’s where I surrender to vagrant scratches and notes on issues of the day, fugitive quotes, hit-and-run readings and reflections picked up from the cutting-room floor.

Between the tyrannies of Twitter, Facebook and texting and the reduction of roughly half American discourse to like buttons, emoticons, acronyms and “diggs,” whatever those are, the reign of the short attention span is culture’s new Caesar. On the other hand the book of hours was basically a medieval blog, and the walls of Lascaux were pre-literate notebooks, better written than most of what’s been done since. So here’s where I surrender to vagrant scratches and notes on issues of the day, fugitive quotes, hit-and-run readings and reflections picked up from the cutting-room floor.

•

A Thomas Jefferson line that never gets old: “But it does me no injury for my neighbor to say that there are twenty gods, or no god. It neither picks my pocket nor breaks my leg.” (From his Notes on Virginia) ↑

•

Norwegian welfare: Watching Elling, a Norwegian movie released in 2001 about two misfits who learn their ways in the world, but not without the generous care and subsidies of the Norwegian government’s welfare state. The humanism of the characters’ slow self-realizations aside, that’s one of the striking things about the movie, the more so because it’s not at all part of the plot or the director’s intention. The normalcy of the welfare state’s safety net is just there, taken for granted and to be taken for granted, like air to breathe and water to drink–and a livable, roomy apartment to live in, and time, with government checks coming, to learn to make one’s way after living in an institution for two years. It’s part of that Norwegian matter-of-factness, a combination, in that national character, of supreme self-assurance–they didn’t call their nutty ocean-braving ancestors Vikings for nothing–with unapologetic social responsibility. It helps to be the world’s 13th biggest oil producer, and to have a population smaller than Colorado’s. But Norway is the only oil-rich country that hasn’t corrupted its government or its social functions on its crude riches. It has used them to, refine, above all, itself. ↑

•

Emerson on Rabelais: A nugget from Emerson’s DeBeers quarry of diamonds (meaning his journals): “Rabelais is not to be skipped in literary history as he is source of so much proverb, story & joke which are derived from him into all modern books in all languages. He is the Joe Miller of modern literature.” If only I knew who the hell Joe Miller is. There were all sorts of baseball-playing Joe Millers in Emerson’s time. ↑

•

Bare Necessities: Not much debate about it. In the pantheon of the greatest music ever written, for me it’s a tie between Bach’s St. John Passion and this. ↑

•

Primary election day: I’ll be glad come 11 p.m. when all the numbers and stories will have been put to bed, me with them. But it pisses me off how even candidates who should know better–Colleen Conklin, for one–still go around talking about voting as a privilege. “Come what may.” Colleen wrote Monday evening on her Facebook page, “I’m looking forward to Wednesday morning! Please, please make sure you go out and take advantage of your opportunity and privilege to vote!” What privilege? It’s a goddamn right if there ever was one. Casting it as a privilege plays into the Republican fraud of the last few years, which has so successfully made voting more difficult–and a privilege, rather than a right–under the guise of fighting (non-existent) fraud. Voters buy the bullshit, too, whether it’s about voting being a privilege or about its alleged abuses. Meanwhile where there are issues with voting fraud (absentee ballots are the problem, and Republicans vote that way far more than do Democrats or Independents), Republicans do nothing. Richard Hasen, a professor of law and political science at the University of California, summed it up in The Times on Aug. 5: “I have not found a single election over the last few decades in which impersonation fraud had the slightest chance of changing an election outcome – unlike absentee-ballot fraud, which changes election outcomes regularly. […] Pointing to a few isolated cases of impersonation fraud does not prove that a state identification requirement makes sense. As with restrictions on absentee ballots, we need to weigh the costs of imposing barriers on the right to vote against the benefits of fraud protection.” There is a solution: “We need to move beyond these voting wars by creating a neutral body to run federal elections and to ensure that all eligible voters, and only eligible voters, can cast a vote that will be accurately counted on Election Day.” But the partisans–Democrats or Republicans–won’t allow it. What makes too reasonable sense in terms of voting rights is toxic to the political advantages of one side or another, which of course have nothing to do with rights and everything to do with the essential fraud at the heart of the current system. ↑

•

Spanking Vidal: Speaking of Vidal, I love this little review of his Judgment of Paris, in the London Times of April 4, 1953: “Mr. Gore Vidal, one of the younger American novelists of whom perhaps too much has been made in this country, continues to ask for more than the normal amount of indulgence given to his clever and demonstrative kind. He has an egocentric shrewdness and unusual fluency of expression, and some of the more restrained passages of comedy in The Judgment of Paris are entertaining enough in their not altogether adult way. But the novel as a whole is high-pitched and pretentious, and in the reading becomes increasingly tiresome.” Odd: I’ve felt the same way about every novel of his I’ve read, his historical novels included. Only the essays sparkle, and even then, it takes constant effort to look past the slabs of Vidalian ego. The Times continues: “Mr. Vidal’s variation on the Jamesian theme of the essential American in contact with the culture of Europe is robbed of real point by his preoccupation with the conventionalities of vice and by the intrusion of his somewhat large and unoriginal personal opinions.” Unoriginal is an unusual word to find in anything to do with Vidal. ↑

•

Uncool: We’ve lost our air conditioning on the second floor here, where all our operations are wired. Something about a coil leaking gas, and dollars. The repairs will be as expensive as a trans-Atlantic trip in high season. We don’t spend the money on that sort of thing out of prudence or lack of it, but a coil springs a leak, and there it is. Spent. Either that or we bake. It’ll make working in sauna conditions interesting. Faulkner of course didn’t have air conditioning either in his stifling Oxford, but he managed to write a few pages once in a while. And there’s always the downstairs air conditioner, which still works. Until this thing is fixed, our stairway to heaven goes downward. ↑

•

•

Updike’s Florida lizards: “No sooner do Russian scientists claim that they have revived two lizards that had been frozen in the Siberian tundra for five thousand years than American scientists announce that there is no life whatever on Venus. In a way, we’re relieved, for there’s so much life in France, Cuba, and the subway these days that it’s a comfort to know there are still a few undeveloped areas in the universe.” From a March 1963 fragment by John Updike, reprinted in his forgotten Assorted Prose (1979). And that was before he discovered the lizarding of Florida. I haven’t quite gotten used to the planet being without Updike. He wasn’t great. But he was grand enough, for these times, and he had at least ten books left in him. And he was a bit of a literary parent, which counted for more than what it sounds considering the premature deaths of my other parents. I had to pick a few subs. Gore Vidal’s death last week wasn’t fun either, though he’d more than had his time, and he really was spent. Unlike Roth or Updike, he’d had nothing left for at least ten years, probably more. He stopped being interesting when his boyfriend died, or when he left his villa in Ravello. But as Updike himself would remind us, “men die, each father in turn has lost a father, it is unmanly and impious to persist in unavailing woe.” ↑

•

Afghan indifference: In March a Times/CBS poll found, about 11 years and a few dozen thousands of deaths too late, that 69 percent of Americans think the United States shouldn’t be in Afghanistan, a number snug with hindsight. The more relevant number is how little Americans care. When Gallup asked its open-ended question–“What do you think is the most important problem facing the country today–72 percent cited the economy, 72 percent cited economic problems, dissatisfaction with government got 12 percent, 11 percent cited the federal budget deficit, and everything else was in single digits. The gap between rich and poor? 1 percent. Corporate corruption? 1 percent. And Afghanistan? 1 percent. The war in Afghanistan might as well not exist anymore. “In marching, in mobs, in football games, and in war, outlines become vague,” Steinbeck wrote in The Moon is Down, “real things become unreal and a fog creeps over the mind. Tension and excitement, weariness, movement–all merge in one great gray dream, so that when it is over, it is hard to remember how it was when you killed men or ordered them to be killed. Then other people who were not there tell you what it was like and you say vaguely, ‘Yes, I guess that’s how it was.'” Afghanistan might as well be a past season’s football game, though chances are more people will remember the scores of every game their team played last year than know the number of dead in Afghanistan so far this year (209 American soldiers, 63 coalition soldiers, a few thousand Afghans. It’s always a few thousand Afghans, whose deaths register even less. ↑

•

Clint Eastwood’s endorsements: You can’t win them all. He can’t shake the Sondra Locke syndrome. ↑

•

Flaubert’s retardations: Flaubert in his youngest days appeared, to his father, “hypersensitive and intellectually retarded,” Henry Troyat writes in his Flaubert biography. “At every turn he isolated himself in a sort of stupor, a finger in his mouth, his look vapid, deaf to whatever was said around him and incapable of pronouncing a single phrase correctly.” This was the man who gave us Madame Bovary and L’Éducation sentimentale, reinventing realism and the novel along the way. I wonder how he would have done on the FCAT. No, I don’t. He’d have failed, intentionally. Genius doesn’t suffer idiocy. ↑

Leave a Reply