[Originally published in the News-Journal on Dec. 21, 2004.]

I’m attracted to cemeteries like a geologist to sediment: You never know what history they’ll turn up, how loudly they speak it behind their loamy stillness. Hidden in the retreating wilderness of pines and palms off Old Kings Road in Palm Coast, the Masonic cemetery doesn’t disappoint. I had driven by it on my way to work every day for three years, never noticing it until my eyes chanced on a cluster of modest tombstones in a split-second square of time between two trees. I doubt my ignorance was unique.

Long buried and forgotten relics of Indian haunts aside, the Masonic cemetery is Palm Coast’s oldest human landmark and the most noble monument to the region’s ancestry. That it happens to be the region’s black ancestry helps explain why the place isn’t even in the margin of Palm Coast’s cares: The cemetery is also the most poignant marker of Flagler County’s past – and indeed lingering – bigotry. The paint is still drying on the first coating of Palm Coast’s history. But considering how little authentic history there is to speak of, it’s striking, if not nearly so surprising from glossy marketing’s perspective, how much of that paint brushes over the essential.

Long buried and forgotten relics of Indian haunts aside, the Masonic cemetery is Palm Coast’s oldest human landmark and the most noble monument to the region’s ancestry. That it happens to be the region’s black ancestry helps explain why the place isn’t even in the margin of Palm Coast’s cares: The cemetery is also the most poignant marker of Flagler County’s past – and indeed lingering – bigotry. The paint is still drying on the first coating of Palm Coast’s history. But considering how little authentic history there is to speak of, it’s striking, if not nearly so surprising from glossy marketing’s perspective, how much of that paint brushes over the essential.

When Flagler County was little more than Bunnell and Bunnell little more than a lumber and turpentine town racially split by the proverbial railroad track, blacks were buried not far from where the old courthouse stands today until white-owned new houses began crowding out the gravesites. Some houses were built on top of those gravesites. By way of compensation blacks were given the site along Old Kings, in what was then, in the late 1940s, a boondocks’ hinterland. Never mind that the miles from town would make it difficult for most to make the trip easily, let alone walk it. Blacks then were in no position to bargain, Bunnell’s intimacies with prejudice being half the reason for the befogged windows on its past. (One of the telling gravestones at the Masonic cemetery belongs to a Roosevelt Stewart, born Dec. 15, 1932, and very likely named for Franklin D. Roosevelt, elected president 37 days earlier. Blacks had great hopes for the Roosevelt presidency, hopes FDR would dash by refusing, amazingly, to support an anti-lynching bill in 1937. For 12 years he wouldn’t jeopardize his coalition of southern Democrats in the name of civil rights.)

Click On: |

The first burials at the Masonic cemetery date back to the early 1950s. The latest, some 100 burials later, to a few weeks ago. A World War I veteran is buried there, so are many World War II veterans and at least two who served in Korea. Some of the graves have been handsomely restored, painted white or bright pink, crowned with polished granite. Some have sagged, cracked, surrendered to moss and weed.

Many are unmarked anymore, their place noticeable only because you sense from a slight cavity in the ground or unexpected symmetry in the grass that they’ve been there a long time. As ITT began building Palm Coast in the late 1970s, the cemetery was coveted for its land. For a while it looked as if it would be the same old story of uprooting blacks to make room for whiter plans. This time a little outrage was enough to drum up the sort of publicity that makes corporations turn a different shade of white. ITT backed off, the dead were left in peace – most of the time. Vandalism has been a problem at the cemetery , most recently in 2003 (and possibly last fall, according to a regular visitor).

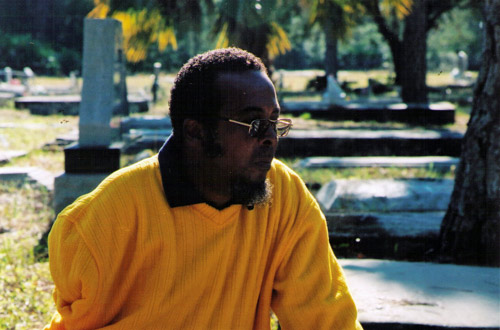

But the nervous person right now is Freeman Jones, a 46-year-old Bunnell native I met one recent morning while I was wandering about the cemetery and he was tending to a few graves with his mother. The cemetery is his family album, each gravesite marking an uncle, an aunt, a niece, a nephew (who lived to be only 1, a victim of sickle cell anemia: “He died at the same time my uncle died, Uncle Clayton, over there”), his father, the midwife who brought him and many of those buried here into the world, the preacher whose sermons he heard as a young boy. Jones’ grandfather is buried beneath one of those houses in Bunnell. He wonders how long it’ll be before the Masonic cemetery is reduced to a single marker, if that, as the city around it grows so sumptuously toward its future that it devours the unquiet past in its way.

![]()

Pierre Tristam is FlaglerLive’s editor. Reach him by email here.

Leave a Reply