By Austin Sarat

Alabama Gov. Kay Ivey has announced a pause in her state’s use of capital punishment. It follows a run of botched lethal injection executions in the state, including two where the procedure had to be abandoned before the inmates succumbed to the cocktail of death drugs.

The last straw appears to have been the failed attempt to put Kenneth Smith to death on Nov. 17, 2022. The state had to call off the procedure after difficulty in securing an IV line.

But that was just the latest execution not to go as planned. In September, Alabama had to stop the execution of Alan Eugene Miller after prison officials poked him with needles for more than an hour because they could not find a usable vein in which to secure an IV.

Even when the execution was carried out resulting in death, the manner has been problematic. When the state executed Joe Nathan James on July 28, 2022, the process – which is normally supposed to be over in a matter of minutes – took more than three hours. During that time, officials tried repeatedly to insert the IV lines necessary to carry the deadly drugs and jabbed James with needles.

In a statement on Nov. 21, Ivey ordered the state Department of Corrections to do a thorough review of the procedures used in executions and asked the state’s attorney general, Steve Marshall, to stop the process for two upcoming executions.

Alabama officials have blamed their problems on what they have described as frivolous, last-minute legal maneuvers by death penalty defense lawyers. In the cases of Miller and Smith, state officials claimed that they ran out of time before the death warrant was due to expire.

But whatever the cause, Alabama’s execution difficulties are not unique to that state.

My research shows that since 1900, in states across the country, lethal injections have been more frequently botched than any of the other type of execution methods used throughout that period. This includes hanging, electrocution, the gas chamber and the firing squad – even though these approaches are not without their problems.

The early history of lethal injection

Lethal injection was first considered by the state of New York in the late 1880s when it convened a blue ribbon commission to study alternatives to hanging. During its deliberations, Dr. Julius Mount Bleyer invited the commission to envision a future in which a person condemned to death “could be executed on his bed in his cell with a 6-gram injection of sulfate of morphine.”

Bleyer and his allies argued that the procedure would be painless. They said that unlike hanging, the method could not be messed up. It also would be cheap, they claimed – all that was needed was a needle and a small amount of morphine.

Lethal injection’s critics told the commission that the method would actually be easily botched, especially if doctors did not conduct the procedure. And even when done right, those in favor of the death penalty as the ultimate sentence further argued that it would be too humane. It would take the dread out of death and dampen capital punishment’s deterrent effect.

Ultimately, lethal injection’s opponents prevailed, aided by the medical community’s unwavering stance against it. Doctors “did not want the syringe, which was associated with the alleviation of human suffering, to become an instrument of death.”

For nearly 100 years after New York’s decision, no jurisdiction in the United States authorized execution by lethal injection. But the early debate over lethal injection foreshadowed arguments that were heard in 1977 during Oklahoma’s consideration of this execution method.

Proponents echoed Bleyer and declared that executions using this method could be accomplished with “no struggle, no stench, no pain.”

This time they won.

The specific drugs to be used in lethal injection – the anesthetic sodium thiopental and pancuronium bromide, a muscle relaxant – would not be chosen until four years later. Although the original law only called for those two drugs, a third drug was soon added: potassium chloride, which causes cardiac arrest.

Together, these three drugs would make up what became the “standard” three-drug, lethal injection protocol. And what started in Oklahoma spread quickly. Lethal injection soon became the execution method of choice across the United States in every state that had the death penalty.

Lethal injection’s troubles

But right from the start, administering lethal injections proved to be a complex procedure that was difficult to get right. In fact, the first use of lethal injection by Texas in 1982 gave a foretaste of some of the problems that would later come to characterize the method of execution.

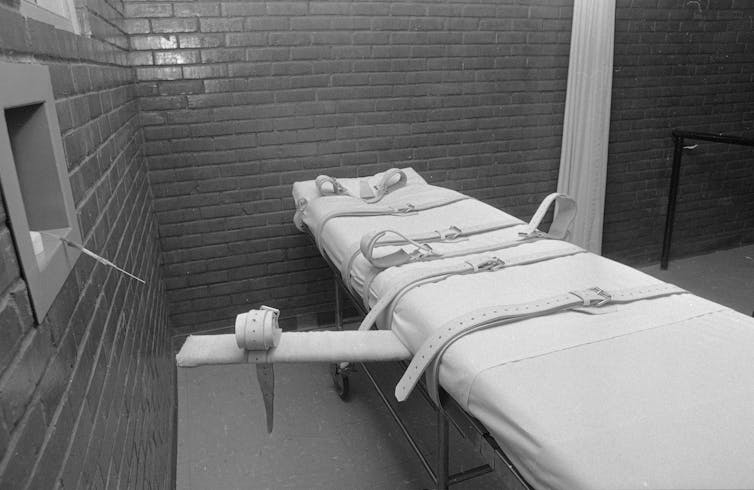

AP Photo/Ed Kolenovsky

The Texas team charged with executing a prisoner named Charles Brooks repeatedly failed in their efforts to insert an IV into a vein in his arm, splattering blood onto the sheet covering his body. And after the IV was secured and the drugs began to flow, Brooks seemed to experience considerable pain.

The difficulties in Brooks’ execution and in subsequent lethal injections result from the fact that medical ethics do not allow doctors to take part in choosing the drugs or administering them. In the place of doctors, prison officials are responsible for the lethal injection procedure. In addition, dosages of the drugs used are standardized rather than tailored to the needs of particular inmates as they would be in a medical procedure. As a result, sometimes the lethal injection drugs don’t work correctly.

Despite the effort to medicalize executions, the history of lethal injection has been anything but smooth, sterile and predictable. In fact, my research reveals that of the 1,054 executions carried out from 1982 to 2010 using the standard three-drug lethal injection protocol, more than 7% were botched.

Since then, owing in part to difficulties death penalty states have had in acquiring drugs for the standard three-drug protocol, things appear to have gotten worse. States have turned to questionable drug suppliers, including compounding pharmacies that are not subject to extensive regulation by the Food and Drug Administration.

In the last decade, states have used no less than 10 different drug combinations in lethal injections. Some of them were used multiple times, while others were used just once.

As states have experimented in the hope of finding a reliable drug protocol, my research shows that botched executions have occurred as much as 20% of the time, depending on which of the newer drug protocols is employed.

During some of those executions, inmates have cried out in pain and repeatedly gasped for breath long after they were supposed to have been rendered unconscious.

In September 2020, an NPR investigation helped explain the high rate of bungled executions. It found signs of pulmonary edema fluid filling the lungs in many of the post-lethal injection autopsies it reviewed. Those autopsies reveal that inmates’ lungs failed while they continued to try to breathe, causing them to feel as if they were drowning and suffocating.

Responding to lethal injection’s problems

Alabama now joins Ohio and Tennessee as states that have paused executions and launched investigations after lethal injection failures. Other states have resurrected previously discredited methods of execution – like electrocution or the firing squad – and added them to their menu of execution options on the books.

Lethal injection’s problems also have contributed to the decision of 11 states to abolish the death penalty since 2007.

Reviewing the history of the different execution methods used in this country, Supreme Court Justice Sonya Sotomayor wrote in 2017: “States develop a method of execution, which is generally accepted for a time. Science then reveals that … the states’ chosen method of execution causes unconstitutional levels of suffering.”

And, referring specifically to lethal injection and its problems, she observed, “What cruel irony that the method [of execution] that appears most humane may turn out to be our most cruel experiment yet.”

![]()

Austin Sarat is William Nelson Cromwell Professor of Jurisprudence and Political Science, Amherst College.

Jimbo99 says

Can’t for the life of me comprehend why any death penalty by lethal injection isn’t as controlled & similar to the many Euthanasia procedures for dogs & cats that Veterinarians perform as a procedure ? One could easily use the Fetanyl or any other illegal drugs that cross the borders or manufactured in home drug house labs and are seized on a daily basis ? I get that it’s a human vs animal thing, but there are drugs that could be administered in such overdose of a quantity that the individual that was overdosed on those drugs would be so oblivious & out of it, that there would be no pain & suffering. The overdose itself and would the chemical substances used in lethal injection even be necessary ?

Perhaps a better comparison would be hospice and morphine that is administered ? With a hospice, the morphine is administered as required and yet there still is no guarantee the one in hospice expires from organ failure. If someone in hospice gets no guarantees of a pain & suffering-less end, why is there any/some debate as to a convicted murderer that was sentenced to death gets a better guarantee or concern that another at end of life doesn’t get.

We just saw the Parkland sentencing. the judge went thru each charge, life imprisonment with no parole was consecutively on all of the individual victims, surviving & deceased. How many lifetimes did they think was just beyond the point/scope of reality of that sentencing. At a certain point of that video I just couldn’t watch it any more because it was too stupid to watch the convicted get 34 life sentences consecutively to the point that his one lifetime was enough. My point isn’t to create a sense of feeling sorry for the criminal. I can only rationalize that the victims & their families, all injured survivors were considered for as much closure as 34 life imprisonments with no parole could be closure.

R. S. says

That’s our culture for you: Deny death to the ones who seek it: the sick, the terminally ill, and the ones sick of life; and hand it out to others just to make vengeful people feel good. What else could its goal be? It certainly doesn’t reduce the number of lethal crimes.

R. S. says

A penalty is generally used for behavior modification. In that respect, the death penalty is a contradiction in terms. Penalties to modify behavior work only on people who continue to live. Added to the “penalty” of dying is the prolonged fear of dying again and again because executions are delayed or are simply applied to the wrong persons. It’s simply barbaric and extremely error prone to use the death penalty. It’s time to join the rest of the civilized world and to abandon this egregious form not of applying justice but of seeking revenge. Besides, it doesn’t deter others: a murder occurs either because of a momentary flare-up of anger or because of a prolonged and careful plan. The murderer who acts on impulse isn’t going to think about consequences; the murderer who plans carefully thinks that s/he can beat the system anyway. The only right we have as a civilized society is to protect ourselves against harm, not to get even. Locking up a person as long as s/he is dangerous is the only sensible form of self-protection.

Ray W. says

The prohibition against cruel and unusual punishments is imbedded in the 8th Amendment to our Constitution. Since our founding fathers understood that vengeful people like this commenter would always exist, they insisted on protecting all of society, including defendants, from people like him or her.

Ray W. says

Somehow, my reply to “The ORIGINALS” comment got attached to your comment when I posted it (lacking the first word “The”) and my reply to your thoughtful comment got lost. Oh, well?

FlaglerLive says

Ray, we have done what we could to restore the comments as you intended.

Ray W. says

My lost comment to R.S.’s thoughtful submission focused on my long-conflicted feelings, re: the death penalty.

Around the age of eleven, as a News-Journal paperboy, I knew that my father had successfully prosecuted Mr. Sirac, a white man who had murdered a Black man at a boat ramp off of S.R. 46 between Sanford and Mims. My father persuaded an all-white jury to convict and recommend death, a first in a Deep South state since Reconstruction. I also knew that my father was opposed to the death penalty. I knew that he sought death because it was his duty as he saw it to follow the law. I later learned that he had been in the bathroom throwing up while the jury deliberated his request.

I knew from an article published by the paper that the pilot who had trained my father’s crew had been murdered by an S.S. detachment when captured, along with a couple of other crew members. Most of the crew had been captured by a Wehrmacht unit and sent to a POW camp. At that time, all pilots flew their first missions as co-pilots with an experienced crew before taking their own crews into combat. I never heard my father speak negatively about the execution of the S.S. officer who commanded the detachment after he was convicted by a war crimes tribunal.

During the summer of my eleventh year, I read for the first time Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings. I long contemplated the effect of Gandalf’s conversation with Frodo while in the mines of Moria. Frodo expressed his thought that it was a pity that Bilbo did not kill Gollum when he had the chance. Gandalf replied that it was pity that stayed Bilbo’s hand, adding that a life taken too easily cannot be restored, so one should be careful when taking life, as no one knows the path to be taken by one who deserves death but does not receive it.

Later in life, as a prosecutor, I worked alongside prosecutors who held the responsibility of deciding who should live or die in this circuit. For years, I watched and listened. Eventually, I concluded that very few people possess the requisite experience, wisdom and insight needed to decide who should live or die, and that very few of that extremely small number of people ever became prosecutors. Stated another way, I learned that most of the people who made that decision in the State Attorney’s office had no business being given that power. When I was told of an opening in that unit, I declined to apply.

Yes, I have long been opposed to the death penalty. But I just can’t shake the understanding that we cannot see all ends. Had Hitler been captured and tried and convicted as a war criminal, but sentenced to life, would his influence have reached beyond the cell fomenting a guerilla insurrection that could have killed thousands of Allied soldiers as Germany rebuilt from scratch a government? If death were an option in the International Court, would Putin have thought twice before visiting war, death, rape, destruction, and despair upon a weaker neighboring country that his own country had promised not to invade? If there is ever a time when the death penalty is a possible deterrent, is it when dictators intend to inflict destruction on a neighboring country?

Academia tells us that there are three types of empires: Empire of Conquer, Empire of Destruction and Empire of Trust. Only the early Roman Empire and the United States of the 20th and 21st Century meet the definition of an Empire of Trust. Can it be argued that Putin initially sought an Empire of Conquer over the Ukraine, but now seeks an Empire of Destruction? Is the death penalty an appropriate sanction when dictators seek to destroy civilizations?

I am not saying I have the answers to this most difficult of questions. I do know that men or women of ambition should never be given the authority to decide who should live or die. I also know that many FlaglerLive commenters, repeatedly commenting that we should just kill them all, are so far removed from any semblance of trust in making such decisions that serious consideration should be given to the absolute abolition of the death penalty, in order to keep them and anyone else like them from ever gaining such power.

R. S. says

Thank you for sharing about your father’s experience. We tend to forget what this heinous form of execution does to the executioners. Prison guards tend to have a ten-year shorter life expectancy as a result of the stress. My father was a member of the SS, joining a cavalry group because he loved horses. Little did he know at age 17 that his regiment would be used to “clean” ghettoes. There were scenes that never left his mind as long as he lived. And Hitler’s death did not prevent partisan activity; there was the “Organisation Werwolf” that continued well after all was lost because they continued to believe in the cause. I am convinced that violence–and the death penalty is a form of violence–does nothing but breed more violence because it affects the mind and the culture.

The ORIGINAL land of no turn signals says

Well,it’s not supposed to feel good.I’d be just as happy with a hanging or firing squad.Did the victim have a choice?

Ray W. says

The prohibition against cruel and unusual punishments is imbedded in the 8th Amendment to our Constitution. Since our founding fathers understood that vengeful people like this commenter would always exist, they insisted on protecting all of society, including defendants, from people like him or her.

R. S. says

And what, pray tell, is that supposed to accomplish? Other than making you feel good?

DaleL says

In general, I’m not a fan of the death sentence as it is typically imposed. However, if the crime is so heinous or a direct attack on our democracy AND the evidence against the accused is so overwhelming as to be without doubt, then I can agree.

For example, Sirhan Sirhan murdered (assassinated) a presidential candidate (attack on our democracy) and was captured at the scene (without doubt). He was sentenced to life, but was recently recommended for parole!

Payton Gendron and Nikolas Cruz are two examples of murderers whose crimes are so heinous and the evidence so overwhelming that I think the death penalty is appropriate. (Gendron had a camera on his helmet and live-streaming his murders!) (Nikolas Cruz was identified through security camera video, numerous eyewitnesses, and physical evidence.)

The death penalty is not about punishing the guilty; it is about closure for the families of the victims and society. It should never be imposed on the basis of a confession or if the evidence against the accused is not overwhelming.

R. S. says

You assume a gradation of penalty that begins with a few months to a few years to a lifetime to death. Again, those assumptions are wrong. If penalties are to modify behaviors, we modify either the behavior of the person penalized or we modify the behaviors by intimidating others who might attempt the same act. Modifying the behavior of others clearly doesn’t work; the statistics are evidence. Modifying the behavior of a person penalized ceases when the person dies. The object of penalty should be the security of the society that is affected by the misdeed. To determine when that security of the society is warranted requires another approach to the entire criminalogical enterprise. Penalties by inflicting harms are very poor ways of educating children; they also fail in educating criminals. The Scandinavian countries have a recidivism rate of 20 percent; our penalty-oriented system has a recidivism rate of 70 percent. You’d think we’d learn!

DaleL says

R. S., you replied to a comment that I did not make. You should not just repeat the same blather as though it is “wisdom”. Repetition is not the same as a meaningful discourse. I wrote: “The death penalty is not about punishing the guilty; it is about closure for the families of the victims and society.”

I never mentioned “a gradation of penalty”, “modifying behavior” or “security of the society”.

I stated that I do not like the death penalty as it is typically imposed. It is too often arbitrary. It has been imposed in cases in which the evidence against the accused was not sufficient.

I described three examples for which I could agree with a death sentence.