Jerry Uelsmann says he’s a documentary photographer.

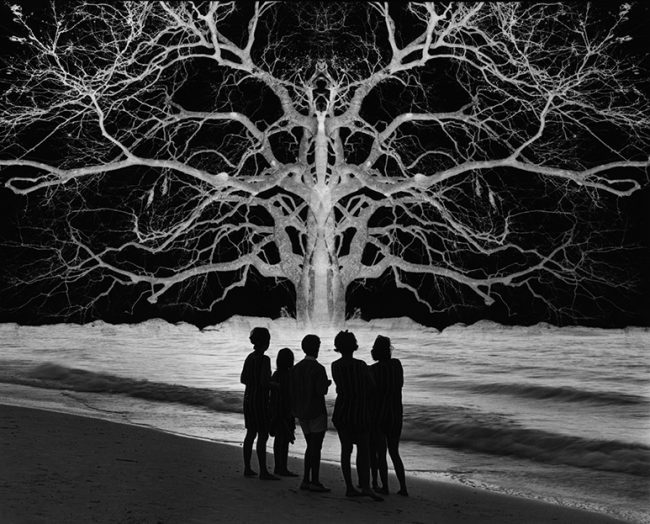

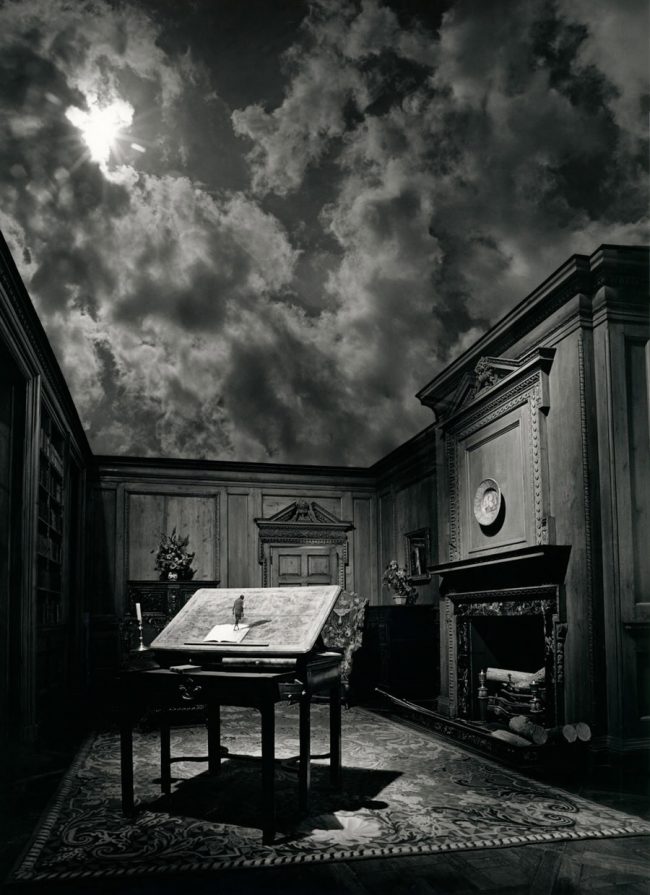

That may come as a surprise to anyone who has seen his surreal, Magritte-like photo-montages in which a row boat sails through the sky, cupped hands hold clouds and Mick Jagger-esque lips sit almost obscenely on a dirt road.

Those and other Uelsmann works have been on exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the International Museum of Photography at the George Eastman House, the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, the Bibliotheque National in Paris, the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography and other international venues.

The photographer’s documentary claim can be assessed when he presents his lecture “Jerry Uelsmann — Alchemy & Angst at 83” at 3 p.m. Sunday Jan. 21 at the Hilton Garden Inn in Palm Coast. The program is part of the Flagler County Art League’s celebration of its 40th anniversary.

“In a certain way, I think my work is documentary,” Uelsmann said during a break from working in his darkroom at his Gainesville home, where he retired in 1998 after a 38-year career as a professor of photography at the University of Florida.

“My work just documents states of consciousness and feelings and things that are very hard to articulate,” he said. “That’s why people are able to connect with the images – they are open-ended in some ways but they document some human condition.”

The documentarian and realism photographers scoffed at such contentions, and at Uelsmann’s work, when he was gaining attention in the late 1960s and early ’70s. Uelsmann’s use of multiple negatives to create a single composite image was gimmicky and “not true photography,” they said, a claim dated by its pre-pixelated presumption (though Uelsmann was and remains a strictly dark room conjurer).

“I have had that criticism,” Uelsmann said. “The way the art world is today, if you could get a color photograph of some dead guy in Afghanistan, you could probably get that in a museum show, because they’re all trying to be so topical. That’s one of the trends. But what I deal with, I think, is also a kind of human condition. It just doesn’t have a described significance because it’s a famous place or because it’s something that’s crucial to what’s going on in the world today.”

Uelsmann was born in Detroit in 1934, became hooked on photography at age 14 and attended the Rochester Institute of Technology – “one of only two places you could really study photography” in the U.S. at that time, he said (the other being the Brooks Institute in California).

At RIT and during graduate studies at Indiana University, he encountered instructors who had “very open attitudes about what photography could be. Suddenly you have a teacher talking about the camera being a metamorphosing machine.”

Shades of Kafka!

After earning his MFA from Indiana in 1960, Uelsmann began teaching photography at the University of Florida as part of the art department, which further widened his perspective.

“That’s a problem photography has had for a long time – that if you’ve got the same camera that Ansel Adams had and you went to Yosemite, you could make those same pictures. That’s such a naïve stupid thing.”

“For many years I was the only photographer on the art faculty,” Uelsmann said. “That’s when my theory of post-visualization was defined. The painter rarely begins with a fully conceived canvas. It’s a process – there’s a dialog with the materials. So being around people like that, once I did some experimenting in the darkroom, I got total support for it — whereas the vast majority of photography is really essentially camera-conceived images. The primary creative gesture is when you click the shutter and then you go in the darkroom and complete that.

“For me, it’s an ongoing process and if I can think of other ways of altering the image in the process, I’m very eager and willing to do that, and I enjoy doing that.”

Uelsmann’s technique involves going on photo safaris, taking dozens or hundreds of black-and-white photos of everyday objects, landscapes, parts of the human body, etc., then making contact sheets (small images of each shot).

With all those tiny photos before him, Uelsmann ignores Einstein’s dictum that God doesn’t play dice with the universe and begins to play with the universe he has laid before himself, shuffling and mixing and matching the realistic images until some juxtaposition strikes his fancy . . . Hmmmm, what would that eyeball look like if it were peering out of a urinal?

Then the real work begins: He takes the negatives of each chosen image into his darkroom, which is home to multiple enlargers, and each negative image is strategically burned onto a portion of the same sheet of photographic paper until some bizarro montage emerges – some scene that would be right at home on, say, “The Outer Limits” television series or in an illustrated edition of “Salem’s Lot” by horror writer Stephen King.

Indeed, Uelsmann works have been used in both those instances.

The inspiration, if not the sampling, behind the result is often difficult to miss: it’s impossible not to see Magritte’s recurring motif of the incongruous monolith in “The Active Voice,” “The Invisible World“or “The Glass Key” in Uelsmann’s “Untitled (Floating Rock)” or “Korean Mystery,” or Magritte’s ubiquitous eye in Uelsmann’s more blunt or peeping variations. The distant silhouettes of his landscapes evoke the enigmas of Giorgio de Chirico. And his cupped hands–well, they’re everywhere, an Uelsmann signature as pronounced as Dali’s mustache.

Uelsmann acknowledged the influence with a 1965 homage he titled “Magritte’s Touchstone” (which Uelsmann later tweaked/recast/re-created to produce several versions).

Though Uelsmann has noted he was exposed to the Surrealists in art history classes during his graduate work at Indiana University, in a 1991 interview with the Los Angeles Times he said: “When people told me to look at the work of Magritte, it was like seeing an old friend. I really related very strongly to that work, but it was more or less after I produced some images that someone said ‘Hey, you should look at this work.’ ”

But don;t call it PhotoShop. Not that Uelsmann disdains PhotoShop and its God-like manipulative abilities. He’s just an old-school analog guy who prefers to create the way he always has.

“People fixate on the craft. That’s a problem photography has had for a long time – that if you’ve got the same camera that Ansel Adams had and you went to Yosemite, you could make those same pictures. That’s such a naïve stupid thing. It’s like what typewriter or computer are you using to write that book?”

The “Alchemy” in his lecture title is easy to fathom: Yes, Uelsmann is a photo alchemist turning base negatives of everyday life into phantasmagoric, surrealist gold. But where does the “Angst” come in?

“Sometimes people think if you have a career in art that you have some gift that is divinely inspired or whatever,” he said. “I mean, I work very hard at what I do. And I make a lot of unresolved images. But that’s part of it.

“And there is an element of angst. If you know exactly what an image is going to look like at the beginning, that’s one thing – you’re done. But I have this constant, ongoing process that’s sort of creating the mountain I’m climbing, to see where it can all go.”

–Rick de Yampert

![]()

“Jerry Uelsmann — Alchemy & Angst at 83” will be presented at 3 p.m. Sunday Jan. 21 at the Hilton Garden Inn, 55 Town Center Blvd., Palm Coast. Tickets are $15, available at flaglercountyartleague.org or by calling 386-986-4668.

P says

This was a fantastic talk by one of the masters of photography and art! Thank you for sharing this or I might have missed it.