If you haven’t seen the movie “42,” the story of Jackie Robinson’s ascension to the Major Leagues back in 1947, you really should. Not because it’s a great movie–it is formulaic and a little too glossy for the era it portrays–but because almost seven decades have passed since Robinson broke baseball’s color line, and that’s time enough for a lot of people to forget, or to have never known, how important a figure Robinson is in the history of our country.

It’s hard to imagine, in this era of ESPN’s multi-channels and 24-hour sports talk radio, the strength of baseball’s grip on an America trying to get back to normal in the early years after World War II. Baseball was, as we’ve been reminded, hot dogs, apple pie and Chevrolet–even though that jingle was actually a bit of ’70s nostalgia. Black men who could swing a bat, were fleet afoot and could throw a curve ball were consigned to the Negro Leagues. Only rarely, in exhibition games, were they allowed to match their skills against those of the reigning white players of the day.

It’s hard to imagine, in this era of ESPN’s multi-channels and 24-hour sports talk radio, the strength of baseball’s grip on an America trying to get back to normal in the early years after World War II. Baseball was, as we’ve been reminded, hot dogs, apple pie and Chevrolet–even though that jingle was actually a bit of ’70s nostalgia. Black men who could swing a bat, were fleet afoot and could throw a curve ball were consigned to the Negro Leagues. Only rarely, in exhibition games, were they allowed to match their skills against those of the reigning white players of the day.

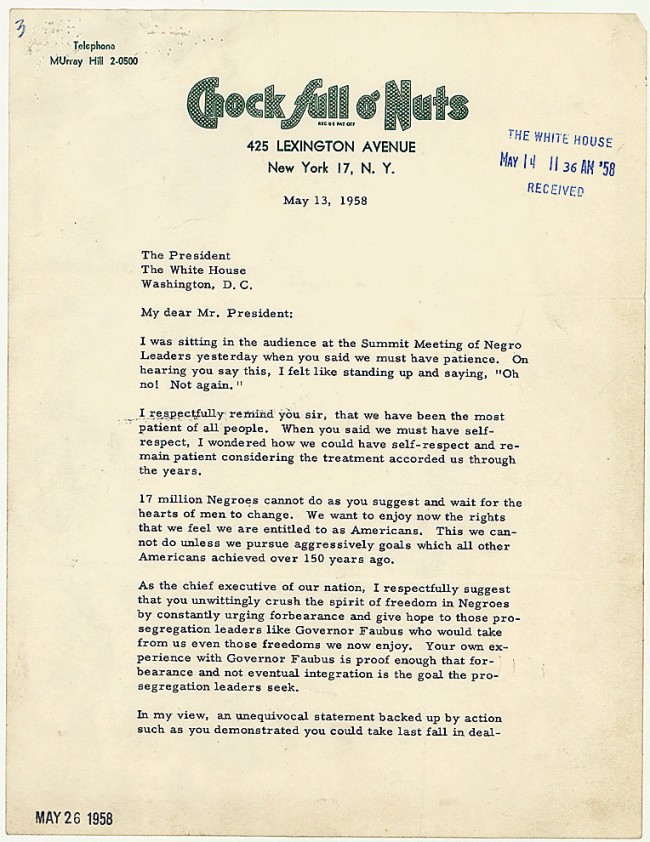

One man, Brooklyn Dodgers president Branch Rickey, for reasons that had as much to do with money as morality, decided this separate-and-unequal arrangement could no longer be justified. Rickey’s decision to sign Robinson to a Major League contract was as important a step toward the integration of American society as was President Harry Truman’s decision to fully integrate the armed forces in 1948.

What is undoubtedly the most shocking image in the film is also brutally real: Phillies manager Ben Chapman, standing several paces in front of his dugout, lobbing the N-word at Robinson in a machine-gun staccato. An acquaintance of mine, aware of my knowledge of sports history, asked me recently if Robinson really had such a hard time during that first season. In the America of 1947, Ben Chapman was permitted to verbally assault Robinson with that vilest of insults with no penalty or punishment. Does that answer the question?

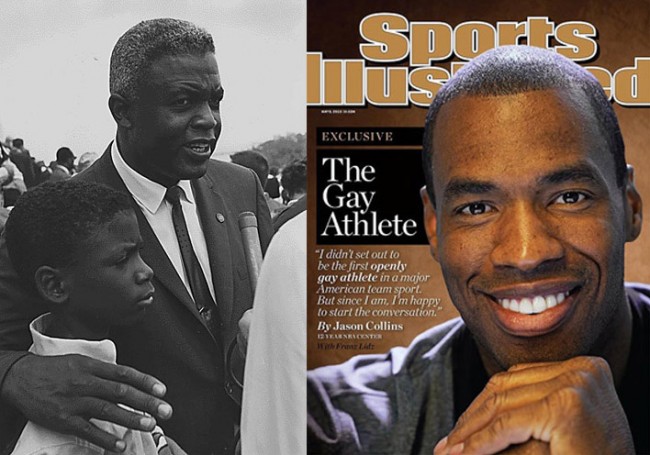

There is another reason why young people in particular should learn about Robinson’s courage, and why his name graces that little bandbox stadium on East Orange Avenue in Daytona Beach. This week, we are hearing about Jason Collins, a veteran NBA center, who has made the brave decision to reveal that he is gay.

Just this month, women’s basketball star Brittney Griner openly discussed her lesbianism, an admission that was widely met with yawns and a large endorsement deal from Nike. But male professional athletes are a different story. The world they inhabit may be turn out to be as perilous a place for Collins and other openly gay men as baseball’s locker rooms were for Jackie Robinson in 1947.

“At a moment when millions are reflecting on the life and legacy of Jackie Robinson, Jason Collins is a hero for our own times,” said Human Rights Campaign President Chad Griffin in a statement on HRC’s Website.

It is fashionable to declare that gay rights is this generation’s civil rights struggle, and indeed prohibitions on gay marriage may seem as unfathomable to future generations as, say, black and white water fountains.

And yet, it would not be entirely accurate to conflate Robinson’s ordeal and his achievement with that facing Collins–who, by all accounts, has been a well-respected citizen during his long NBA career. For one thing, by integrating baseball, Branch Rickey placed his sport well ahead of a society still beset by Jim Crow laws and de facto segregation. Robinson, and the black players who joined him in the late ’40s and early ’50s, dared white America to catch up with the idea that black men could not only compete with but also defeat whites at whatever endeavors they might choose.

Conversely, Collins, as the first major “out” male athlete, will sadly find himself dragging his team, his league, indeed the entire sporting landscape begrudgingly to a brightly-lit place where most of this country has already arrived. It will be his misfortune to be labeled the “gay Jackie Robinson.” Like Robinson, he may have to endure a painful personal burden. But history is less likely to view him as a pioneer than ask instead: “what took so long?”

![]()

Steve Robinson moved to Flagler County after a 30-year career, in New York and Atlanta, in print, TV and the Web. He previously wrote about Neil Reed and Bobby Knight. Reach him by email here.

Anonymous says

A person can’t control what race their birth certificate says, but a person can control whether they enter into a relationship with the same-sex. Two different struggles. Every group discriminated against needs to be compared to the “gay struggle” if people are going to go about it like that that, not just African Americans and the civil rights movement. Can’t wait to see how many people come out and support all the other “don’t tell me what to do” alternative family’s that are going to want their day also.

Linda says

Thank you for an opinion I can respect. I do not want to hear that this compares to Jackie Robinson. This is more in the category of Marlo Thomas’s phrase “Free to Be Me.” While meritorius to take the chances with his career that Jason Collins has taken, it is so far removed from the segregation, hate, and violence that Jackie Robinson, his family, and his supporters endured. I sincerely doubt that the FBI will have to watch over Jason Collins or that stacks of life-threatening letters will be written.

That said, I am glad Mr. Collins chose to liberate himself from the secrecy he thought, and probably rightfully so, he had to maintain to pursue the sport and career. “Free to Be Me.” Only a few years back, it would have destroyed all that.