By Christopher W. Callahan and Justin S. Mankin

Home runs are exhilarating – those lofting moments when everyone looks skyward, baseball players and fans alike, anxiously awaiting the outcome: run or out, win or loss, elation or despair.

Over the past several Major League Baseball seasons, home run numbers have climbed dramatically, including Aaron Judge’s record-breaking 62 homers for the New York Yankees in 2022.

Baseball analysts have pointed to many different factors for this surge, from changes in baseball construction to advances in game analytics.

Our new study, published April 7, 2023, offers solid evidence for another cause – rising global temperatures.

What we learned from 100,000 baseball games

The physics tell a simple and compelling story: Warm air is less dense than cool air. As air heats up and molecules move faster, the air expands, leaving more space between molecules. As a result, a batted ball should fly farther on a warmer day than it would on a cooler day owing to less air resistance.

This simple physical link has prompted speculation from the media about the connection between climate change and home runs.

But while scientists like Alan Nathan have shown that balls go farther in higher temperatures, no formal scientific investigation had been performed to prove that global warming is helping fuel baseball’s home run spree – until now.

In our study, published in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society in collaboration with anthropologists (and baseball fans) Nathaniel J. Dominy and Jeremy M. DeSilva, we used data from over 100,000 Major League Baseball games and 200,000 individual batted balls, alongside observed game day temperatures, to show that warming temperatures have, in fact, increased the number of home runs.

Based on data between 1962 – when Mickey Mantle was American League MVP and Willie Mays topped the home run chart – and 2019, we found that a game that is 10 degrees Celsius (18 degree Fahrenheit) warmer than the average game would have nearly 20% more home runs than average.

AP Photo/Gregory Bull

So, what about everything else that drives home runs?

We can’t run a controlled experiment where we replay each pitch cast since the 1960s and vary only the temperature to assess its effect on home runs. But we can use the trove of data on home runs and temperature to statistically estimate its effect. Whether a game is hotter or cooler than average is not likely to be related to other factors driving home runs, like ball construction, steroid abuse, game analytics or elevation differences among ballparks. This fact allows us to statistically isolate the role of temperature.

To verify our game-level model, we use data from high-speed cameras that ballparks have had since 2015. The cameras provide the launch angle and launch velocity of each hit – 200,000 of them were included in our study. This means we can compare a ball coming off a bat at the same angle and velocity on a warm day and a cool day – near-perfect experimental conditions.

The high-speed camera model nearly exactly replicated the effect of temperature on home runs that we estimated with the game-level data. With this observed relationship between game day temperatures and home runs in hand, we were able to use experiments from climate models to estimate how many home runs have occurred because of climate change so far.

We found that more than 500 home runs since 2010 could be directly linked to reduced air densities driven by human-caused global warming.

More homers in a warming future

We can use the same approach to make estimates about home runs in the future.

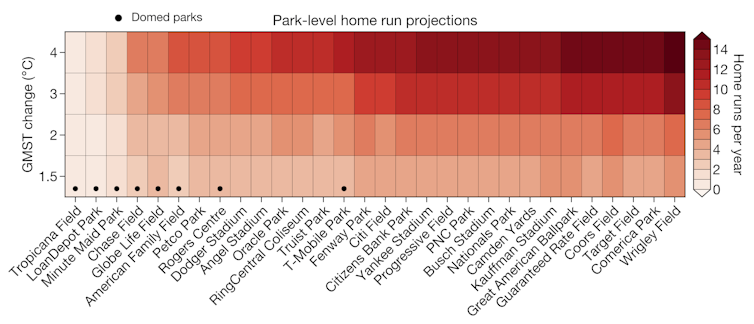

For example, if the world continues to pump out greenhouse gas emissions at a high rate, the temperature will continue to climb, and that could soon yield several hundred additional home runs per year. It could add up to several thousand home runs cumulatively over the 21st century.

Christopher W. Callahan, CC BY

Teams have ways to counter the heat. They can shift day games to be played at night, for example, or build domes over ballparks. In Denver, where the air is less dense because of its higher elevation, the Rockies started storing game balls in a humidor in 2002 to make them “mushier,” increasing their weight and giving pitchers more of a sporting chance.

It’s not all high-fives

More home runs might sound exciting, but that boost in homers is also a visible sign of the much larger problems facing sports and people worldwide as the planet warms.

Rising temperatures will threaten the health and safety of baseball players, fans in ballparks and people around the world. Without serious efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, rising temperatures will transform nearly all aspects of society, from cultural touchstones like baseball to basic human well-being.

![]()

Christopher W. Callahan is a doctoral student in Climate Science at Dartmouth College. Justin S. Mankin is an Assistant Professor of Geography at Dartmouth College.

Pogo says

@Christopher W. Callahan and Justin S. Mankin

Put in terms the baseball pool might get: It’s the bottom of the ninth, bases empty, with two outs, the human race trails by 70 years, er uh, runs…

And so it goes.

Ray W. says

Hasn’t helped my homer-starved Nationals, even with all the hot air produced in D.C.