By Matthew Wright, Nicholas Leach and Shirin Ermis

The earth’s climate experienced its hottest year in 2024. Extreme flooding in April killed hundreds of people in Pakistan and Afghanistan. A year-long drought has left Amazon river levels at an all-time low. And in Athens, Greece, the ancient Acropolis was closed in the afternoons to protect tourists from dangerous heat.

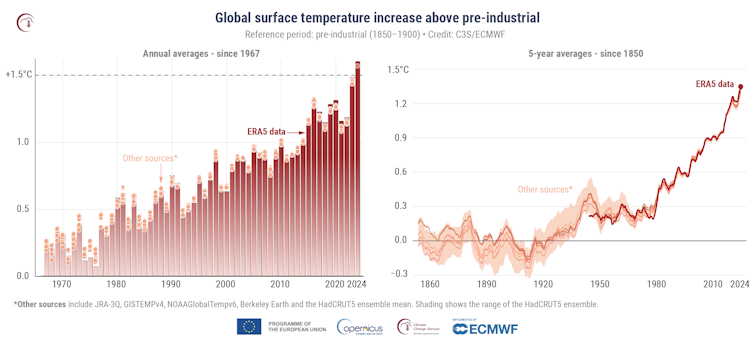

A new report from the EU’s Copernicus Climate Change Service confirms that 2024 was the first year on record with a global average temperature exceeding 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels. All continents except Australasia and Antarctica experienced their hottest year on record, with 11 months of the year exceeding the 1.5°C level.

Global temperatures have been at record levels – and still rising – for several years now. The previous hottest year on record was 2023. All ten of the hottest years on record have fallen within the last decade. But this is the first time a calendar year has exceeded the 1.5°C threshold.

2024 in context: graphs of global mean surface temperature

Copernicus Global Climate Highlights Report 2024

The heat is on

Scientists at Copernicus used reanalysis to calculate the temperature rises and estimate changes to extreme events. Reanalysis is produced in real-time, combining observations from as many sources as possible – including satellites, weather stations and ships – with a state-of-the-art weather forecasting model, to build up a complete picture of the weather across the globe across the past year. The resulting dataset is one of the key tools used by scientists globally to study weather and climate.

Limiting sustained global warming to 1.5°C is a key target of the Paris agreement, the 2015 international treaty which aims to mitigate climate change. The 195 signatory nations pledged to “pursue efforts” to keep long-term average warming below 1.5°C.

While reaching 1.5°C in 2024 is a milestone, surpassing 1.5°C for a single year does not constitute crossing the Paris threshold. Year-to-year fluctuations in the weather mean that even if a single year surpasses 1.5°C, the long-term average may still lie below that. It is this long-term average temperature that the Paris agreement refers to. The current long term average is around 1.3°C.

Natural factors, including a strong El Niño, contributed to the increased temperatures in 2024. El Niño is a climate phenomenon that affects weather patterns globally, causing elevated ocean temperatures in the tropical Pacific. It can raise global average temperatures and make extreme events more likely in some parts of the world. While these natural fluctuations enhanced human-caused climate change in 2024, in other years they act to cool the earth, potentially reducing the observed temperature increase in a particular year.

While targets focus the minds of policymakers, it is important not to over-fixate on what are, from a scientific perspective, fairly arbitrary targets. Research has shown that catastrophic impacts, such as a rapid and potentially irreversible melting of the Greenland ice sheet, become more likely with every small amount of warming. These effects may occur even if thresholds are only passed temporarily. In short, every tenth of a degree of warming matters.

Unprecedented extremes

What ultimately affects humans and ecosystems is how global climate change manifests in regional climate and weather. The relationship between global climate and weather is non-linear: 1.5˚C of global warming may lead to individual heatwaves which are much hotter than the average increase in global temperatures.

Europe recorded its hottest year in 2024, which manifested in severe heatwaves, especially in southern and eastern Europe. Parts of Greece and the Balkans experienced wildfires burning large areas of pine forest and homes.

This new report shows that 44% of the globe experienced strong or higher heat stress on July 10 2024, 5% more than the average annual maximum. Especially in low-income countries, this can lead to worse health outcomes and excess deaths.

The report also highlights that atmospheric moisture content (rainfall) in 2024 was 5% higher than the average for recent years. Warmer air can hold more moisture and water is a potent greenhouse gas, which traps even more heat in the atmosphere.

More worryingly, this higher moisture content means extreme rainfall events can become more intense. In 2024, many regions suffered from destructive flooding, such as that in Valencia, Spain, last October. It is not as simple as more moisture content leading to more extreme rainfall: the winds and pressure systems which move weather around also play a role and can be impacted by climate change. This means that rainfall may intensify even faster in some regions than the atmosphere’s moisture content.

To ensure that warming does not exceed 1.5°C for a prolonged period, and avoid the worst effects of climate change, we need to rapidly reduce greenhouse gas emissions. It is also vital to adapt infrastructure to and protect people from the unprecedented extremes caused by current – and future – levels of warming.

With cooler conditions in the tropical Pacific, it remains to be seen if 2025 will be as hot as 2024. But this new record should highlight the huge influence that humans are having on our climate, and be a wake-up call to us all.

![]()

Matthew Wright is a doctoral candidate at the Department of Atmospheric Physics, University of Oxford, Nicholas Leach is a Postdoctoral Researcher, in Climate Science and Shirin Ermis is a doctoral candidate in Atmospheric Physics, both at Oxford.

Endless dark money says

But boot licking Ron banned even acknowledging it’s a problem in the not so free state of florduh.

Faster than expected ! Should increase significantly from here. We’ve know for over 100 years but chose profits over people. Now go take out that 30 year mortgage on the water lol!

Ed P says

Next someone will probably blame the hundreds of millions metric tons of carbon dioxide being infused into the atmosphere because of the California wildfires over the same period. Or the 2019 Amazon wild fires and deforestation. Or maybe the underground coal fire that has been burning for 6000 years in Australia. Or even the Centralia Pa. coal fire burning since 1962.

50 years is simply too short of a time frame to make any credible statement about climate change. In fact, scientifically the earth is is currently in the ice age called Quaternary glaciation.

However, the “researchers” are correct that average temperature has been warming over the last century.

Might be time to get on board with ocean desalination water facilities.

Not a climate denier, just not willing to chuck my gas stove, grill, dishwasher, or gas guzzling SUV.

DaleL says

The 6,000 year underground coal seam fire in Australia is known as the “Burning Mountain”. It is near Wingam, New South Wales.

I don’t have a gas stove and I never will. It is for two reasons. First there is the difficulty in cleaning the cook top versus that of a smooth top electric. The second reason is indoor air pollution. That doesn’t stop me from having an outdoor gas grill.

The California wildfires are largely the result of population growth. One hundred years ago, the locations that are burning today, were barren hills. Similarly, more people = more cars, planes, homes, factories = more CO2 The Earth has an estimated 8.2 billion people. That number is growing every day.

The 1.5 degree Celsius “limit” is arbitrary. 55 million years ago, during the Paleocene/Eocene thermal maximum, alligators lived as far north as the arctic circle. There were no polar ice caps. From about 115,000 to 12,000 years ago, there was a mile thick glacier over what is now Cleveland. The ground in norther Ohio is still rebounding up as a result of the ice melting.

Global warming is true. Florida and other low coastal areas will be flooded by rising seas. However, we can reduce

the rate of change. I care not if my property is underwater in 500 years. It matters to me a lot if it floods within the next 10 years.

Sherry says

“Climate Change” is just a hoax, right? Do not believe your lying eyes, or those scientists. . . stay Maga brain dead strong!

Sherry says

OOPS! I forgot to say. . . don’t despair trump will fix it all! You can bet the lives of your children and grandchildren on trump your savior! LOL! LOL! LOL!

Foresee says

Alligators have existed for over 200 million years, with their ancestors appearing during the Late Triassic period. Humans (Homo Sapiens) have been around for approximately 300,000 years. True, in Earth’s history species have come and gone. But what took so long for humans to arrive on the scene? It’s not the time it takes for complex genetics to organize a conscious brain. Daphnia, the water flea, has more genes than humans.

In Earth’s history there have been several mass extinctions, the latest being the KT event 65 MYA (an asteroid hit the earth and wiped out 50-70 % of all species). So why the late appearance of humans? It’s the Goldilocks Principle- conditions were just right, not too hot, not too cold for humans to evolve.

If people prefer to live in conditions when dinosaurs and alligators were comfortable, fine, keep ignoring anthropogenic climate change.

“The California wildfires are largely the result of population growth.” Wrong, it’s cause was/is climate change caused by human disregard for the environment.