By Julia Khrebtan-Hörhager and Evgeniya Pyatovskaya

The race for the presidential post in France began with 12 candidates. It will conclude on April 24 with the same choice that confronted voters five years earlier: the centrist Emmanuel Macron or the far-right Marine Le Pen.

Sequels tend to be less inspiring, and the election as a whole has failed to spark widespread enthusiasm among many disappointed and often apathetic voters, despite the starkly different visions for France displayed by the candidates.

Before the field was narrowed on April 10, French voters had a quintet of front-runners from across the political spectrum to choose from: Le Pen was being outflanked on the far right, and the far left was at one point surging. Meanwhile, centrist candidates including Macron seemingly failed to get much traction, and the right-wing Valérie Pécresse, representing the once powerful but now divided Les Républicains, ran arguably the least successful campaign.

Grand disillusions of La Grande Nation

The election process has not been without intrigue, not least over the polarized positions and debates between the far-left environmentalist Jean-Luc Mélenchon and the far-right polemicist Éric Zemmour. But even here, the two candidates eventually failed to capture enough enthusiasm to propel them into the runoff.

Mélenchon, who prioritized “planification écologique,” or “ecological planning,” which focuses on sustainability, became only partially popular among young voters, many of whom tend toward a global, pan-European viewpoint at odds with Mélenchon’s Euro-skepticism and overall critique of the European Union.

The ultra-right Zemmour captured global headlines through his zealous anti-immigration rhetoric and policies aimed at protecting what he saw as a pure French identity. And he proved quite popular at the beginning of the campaign with a group of youth supporters, numbering around 10,000 members, who called themselves Generation Z.

But that name – and the association – quickly became problematic when the letter “Z” became a symbol of Russia’s ongoing war in Ukraine. Zemmour’s campaign also suffered from another Z–related faux pas that became known as Z chez ZZ/ or “Z at ZZ.” Zemmour was booted out of the soccer club set up by the great Zizou, as former French national player Zinedine Zidane is affectionately known, after turning up uninvited as part of a publicity stunt. Zemmour’s anti-immigration policies apparently did not sit well with the French-Algerian Zidane.

With both extreme candidates’ campaigns faltering, and those of others failing to ignite, one-quarter of French voters stayed away from the ballot on April 10 – the lowest participation rate since 2002.

And neither of the two front-runners got even close to the 50% of the vote needed to avoid a runoff – Macron secured just shy of 28%, with Le Pen second on 23%. But the list of candidates shrinking to just two has done little to inject enthusiasm into the race.

Macron has governed France, one of the most vaccinated nations in Europe, through the COVID-19 crisis and may seem to outsiders as a sure bet – indeed he is thought likely to win the runoff with Le Pen reasonably comfortably. However, Macron is hardly being carried through on a wave of enthusiasm. His tenure as president to date has been marked by disappointment – with an approval rating that now hovers in the low 40s.

His image was harmed by the Yellow Vests movement – protesters who took to the street over the impact of a flat tax and an energy tax. Macron’s handling of the protest resulted in him being widely perceived as an arrogant representative of the French elite.

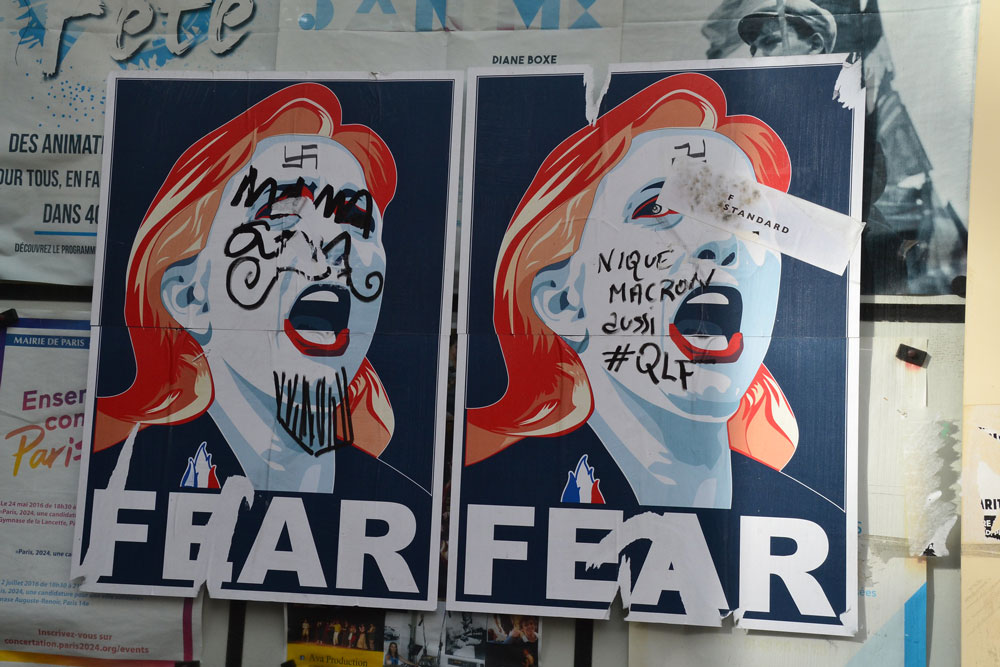

Le Pen’s campaign has centered around making the far-right candidate appear more approachable than Macron by attempting to soften her image – hitherto associated with racism and anti-immigration sentiments.

As the French newspaper Le Monde summarizes, the choice between Macron and Le Pen pits the “France of executives and retirees against France of employees and workers, cities against the periphery, European integration against national sovereignty …” It is a choice not simply between the two very different candidates, but between two different futures.

Déjà Vu: Populist vs elitist

But try as she might, Le Pen will find it hard to extinguish voters’ preexisting reservations concerning the far-right leader. In 2017, Le Pen’s Euro-skepticism, racism, xenophobia and Islamophobia stained her candidacy. It may well keep many from voting for her this time around. Despite trying to soften her image – her promise to not abandon the global climate agreement and to take care of the French rural heartlands have helped in this regard – Le Pen still espouses hard-right positions.

She insists on policies such as imposing fines on Muslim women who wear the veil and advocates for Frexit – a French exit from the EU.

Meanwhile, as the war in Ukraine has shifted the focus of political debates, Le Pen has faced criticism over her apparent admiration for Russian president Vladimir Putin and a previous loan to her party from a Russian bank. Le Pen has had to walk a thin line between repairing her image while upholding her friendship with the Kremlin.

The rapidly deteriorating image of Russia in France might well haunt Le Pen on election day.

Macron, meanwhile, has been trying to re-win voters’ hearts in multiple ways. He is openly opposing the war in Ukraine – to the extent that he has been accused of “cosplaying” Volodymyr Zelenskyy by swapping his usual immaculate suits for the more casual hoodie and jeans preferred by the Ukrainian president. Such sartorial changes are aimed to put across an image of Macron as more approachable, as well as provide a visual juxtaposition to Le Pen’s sympathies for Russia.

Macron has also promised a renewal of his policies to make France an environmental leader of the world.

He aims to reboot the economy, even if that risks potentially unpopular measures, such as pushing back the retirement age from 62 to 65 or tax increases that might lead to even more civil unrest.

It is a fine balance, though. Many families in France are suffering from the increase in the cost of living. Macron has failed to deliver an increase in purchasing power for many voters and has been accused of being “the president of the rich.”

Between plague and cholera, ce sera blanc

One thing appears likely: 2022 will not bring a landslide victory for Macron, especially if the young voters, disappointed in both candidates, abstain. The apathy of the youth, disappointed in both candidates, can significantly alter the election’s outcome.

Environmental issues, particularly important for this demographic, are perceived as being not sufficiently prioritized, as seen in the criticism of the candidates by Clément Sénéchal, spokesperson for Greenpeace France, who described Macron and Le Pen as a “climate cynic” and a “climate skeptic,” respectively.

[Over 150,000 readers rely on The Conversation’s newsletters to understand the world. Sign up today.]

And Macron has also disappointed too many of his young voters with a lack of social dialogue. Some claim that although Le Pen is still worse, it will be humanly impossible to vote for Macron – as if the choice between the two is like the choice between plague and cholera.

Calls to boycott the upcoming election altogether have become louder in recent weeks. Many have vowed to abstain from the vote, claiming “Pour moi ce sera blanc” – “For me, it will be a blank vote.”

![]()

Julia Khrebtan-Hörhager is Associate Professor of Critical Cultural & International Studies at Colorado State University. Evgeniya Pyatovskaya is a doctoral Candidate in Communication at the University of South Florida.

Pogo says

@Julia Khrebtan-Hörhager, Evgeniya Pyatovskaya

“…One thing appears likely: 2022 will not bring a landslide victory for Macron, especially if …”

Your chances were 50/50. Oh well. Back to the Ouija board.

He realized suddenly that it was one thing to see the past occupying the present, but the true test of prescience was to see the past in the future. Things persisted in not being what they seemed.

— Frank Herbert