A U.S. Supreme Court decision striking down Florida’s death-penalty sentencing structure is a “tectonic shift” that should be applied retroactively to all inmates on Death Row, lawyers for a convicted murderer scheduled to be executed in February wrote in court documents filed Friday.

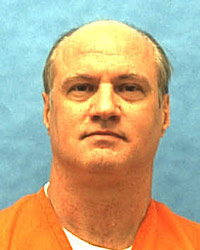

Lawyers for Cary Michael Lambrix, who has been on Death Row for more than three decades, have asked the Florida Supreme Court to halt his execution and allow a lower court to sort out whether the U.S. Supreme Court decision, in a case known as Hurst v. Florida, applies to Lambrix.

In an 8-1 decision this month, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that Florida’s method of using juries to recommend death sentences, but giving judges the power to impose the sentences, is an unconstitutional violation of the Sixth Amendment right to a trial by jury.

The decision focused on what are known as “aggravating” circumstances that must be found before defendants can be sentenced to death. A 2002 U.S. Supreme Court ruling, in a case known as Ring v. Arizona, requires that determination of such aggravating circumstances be made by juries, not judges.

The Jan. 12 ruling has “far-reaching effects on capital litigation in Florida,” requiring more time to digest than is available under the current “expedited” court schedule prompted by the pending death warrant, signed by Gov. Rick Scott in November, Lambrix’s lawyers argued Friday in a 106-page brief.

Attorney General Pam Bondi’s lawyers argued earlier this week that the Hurst ruling should not affect Lambrix’s case because his sentence came before the 2002 decision in Ring v. Arizona.

Following the Hurst ruling, the state Supreme Court gave Lambrix’s lawyers an extra two days — until Friday — to file a brief explaining its impact on his case, and whether it applies retroactively to inmates already on Death Row.

The Florida Supreme Court has typically given inmates condemned to death a year to interpret death penalty decisions issued by the U.S. Supreme Court, Lambrix’s lawyers objected, reiterating their request that state justices postpone his execution, scheduled for Feb.11.

“Hurst requires a global paradigm shift in our understanding of the Sixth Amendment aspects of Florida’s death penalty scheme. Hurst establishes that our most basic assumptions about the constitutional integrity of Florida’s scheme were wrong. It necessarily opens up new approaches to understanding what is, and is not, unconstitutional in what remains of that scheme,” the lawyers wrote.

Lambrix was convicted of killing Aleisha Bryant and Clarence Moore in Glades County in 1983. According to court documents, Lambrix met the couple at a LaBelle bar and invited the pair to his mobile home for a spaghetti dinner.

Lambrix went outside with Bryant and Moore individually, then returned to finish the dinner with his girlfriend. Bryant’s and Moore’s bodies were found buried near Lambrix’s trailer.

Lambrix was originally scheduled to be executed in 1988, but the Florida Supreme Court issued a stay of that execution. A federal judge lifted the stay in 1992.

Lambrix has argued that his previous lawyers were ineffective, that he suffers from post-traumatic stress disorder and that the trial court erred in denying DNA tests for a tire iron, Bryant’s clothing and a shirt wrapped around the tire iron. Lambrix contends that Moore sexually assaulted Bryant and killed her and that Lambrix killed Moore in self defense.

A jury recommended that Lambrix be sentenced to death, and a judge imposed the death sentence under the process that the U.S. Supreme Court ruled was unconstitutional, Lambrix’s lawyers wrote.

The Florida Supreme Court should apply Hurst retroactively, as it did after a U.S. Supreme Court ruling about the constitutionality of juveniles being sentenced to life in prison, Lambrix’s lawyers wrote. Last year, the Florida justices gave inmates who had been sentenced to life as juveniles two years to seek new sentences from trial courts.

But the court could go further and follow its reaction to a 1972 ruling in a case known as Furman v. Georgia that resulted in a nationwide moratorium on the death penalty. The Furman decision found that the death penalty could not be imposed under procedures that create a substantial risk that it would be applied in an arbitrary and capricious manner.

The Florida Supreme Court converted all death sentences into life imprisonment in response to the Furman ruling, Lambrix’s lawyers noted.

“Interestingly, there was no question, no statutory interpretation, no retroactivity analysis, no harmless error analysis, no recalcitrance, and no attempts to save prior death sentences and still go forward with undeniably unconstitutional executions,” the lawyers wrote.

Allowing defendants who haven’t been sentenced yet to get sentenced under a new structure would be unfair, Lambrix’s lawyers argued.

No one “skates or goes free” if the nearly 400 inmates on Death Row have their sentences converted into life imprisonment without parole, the lawyers wrote. But letting some defendants get sentenced under Hurst would raise the specter of an arbitrary and capricious sentencing structure found unconstitutional in the Furman decision, they wrote.

Lambrix’s lawyers also asked the Florida Supreme Court to send his case back to a Glades County judge for an evidentiary hearing so he can challenge the validity of his convictions and sentences.

Federal public defenders and the American Civil Liberties Union of Florida filed friend-of-the-court briefs in the Lambrix case, agreeing that the Hurst decision should be applied retroactively and that Lambrix’s execution should be delayed so that a lower court can decide about the implications of the ruling.

“Put simply, death sentences imposed with a judge’s, but not a jury’s findings on the defendant’s eligibility for capital punishment are unconstitutional. The question should not be how many executions based upon such unconstitutional sentences will Florida tolerate before Hurst is given effect. This (Florida Supreme) Court’s history of adherence to principles of fundamental fairness opposes such a miserly approach,” Billy H. Nolas, chief of the Capital Habeas Unit of the Federal Public Defender for the Northern District of Florida, argued in a brief.

–Dara Kam, News Service of Florida

Leave a Reply