It’s not just the Oscars that are creepily white this year. In the last 60 years you could count on one and a half hands the number of notable American films featuring black cowboys. And even those have happened only about once a decade: Jamie Foxx in “Django Unchained” (2013), Morgan Freeman in “Unforgiven” (1992), Danny Glover in “Silverado” (1985), Cleavon Little in “Blazin’ Saddles” (1974). Blacks

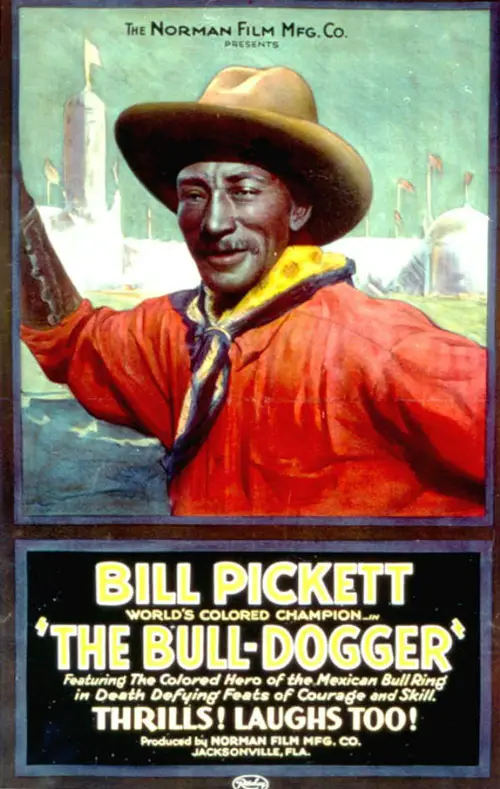

But just as blacks had been part of Columbus’s maiden voyage to the Americas and of the Lewis and Clark expedition across the West, black cowboys were very much part of 19th century pioneering and settled societies in the growing United States. In Texas, where Bill Pickett—one of the more famous black cowboys—was born, some estimates place the proportion of black cowboys in the 19th century at one in four. The proportion of Mexican cowboys, whose word vaquero is at the origin of the word cowboy and who taught their white brethren most of what they came to know by way of ranching, was even greater.

Scholarly literature on back cowboys in Florida is scant. That’s a shame, considering what is known about black ranching in the state: it’s been part of Florida’s history. To what extent?

That’s less clear. What’s certain is that it’s been part of Florida’s true stories. It’s also what led Mary K. Herron, whose family has been in Florida since 1859, to explore the story further. She loves such stories, she says, “especially if they are underreported.” A trained archeologist who’s worked in Florida and the Caribbean, she is the director of development at the Florida Agricultural Museum at the north end of Palm Coast, “and I’m interested in my state’s history, especially when I come across stories that should be told and haven’t been,” Herron says.

“In a general sense, even in the west, it was true that lots of cowboys weren’t white,” Herron says, “but certainly in Florida, probably all the way through the colonial era, they weren’t white. For one thing there wasn’t enough population. And cowboying, it’s not really that romantic except in the movies. It’s hard work, and it’s dangerous.”

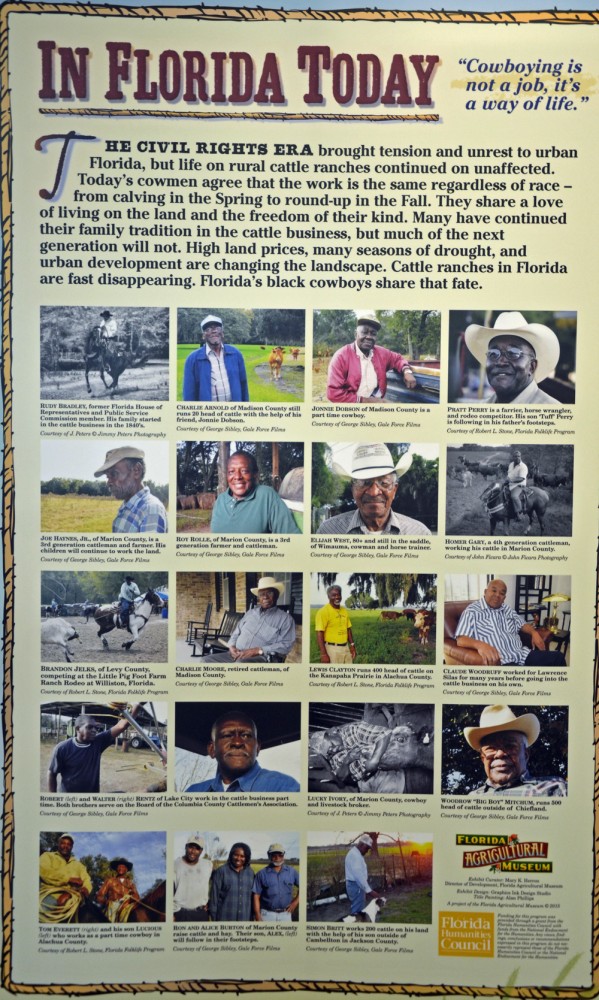

Of course it’s not just about setting the record straight. “I wanted to tell the story because it shows the continuity of something that’s really quintessential to Florida life even today,” Herron said. “and that is the cattle industry, and how since its introduction to Florida, it’s always been linked to people of African descent. It still is.” Curiously, she noted, the 2008 housing collapse was good for ranching: it stopped the selloff of land to developers, and people returned to ranching.

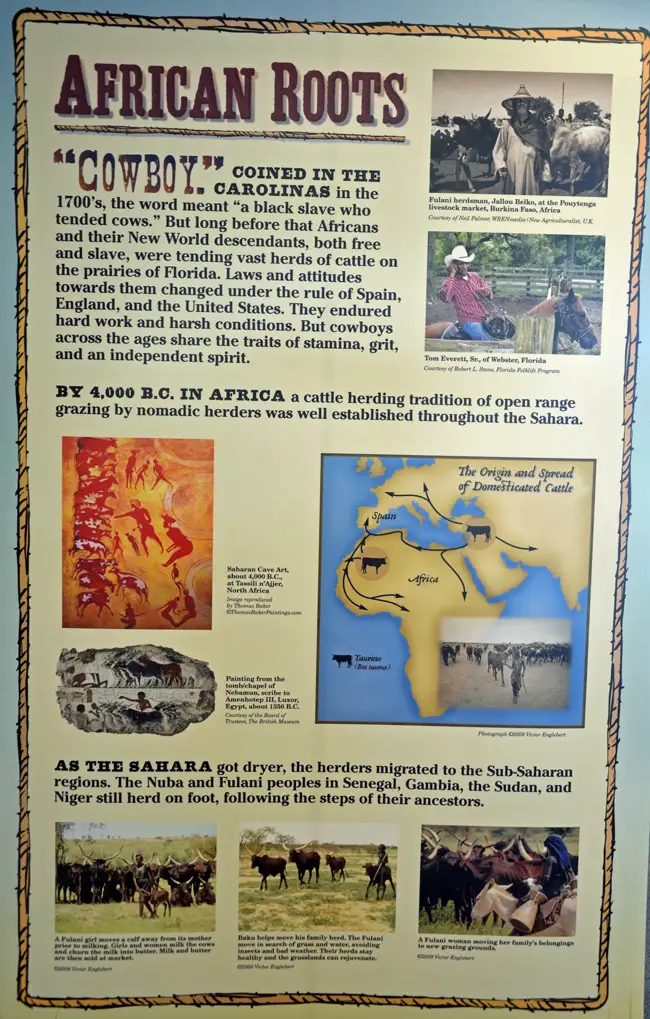

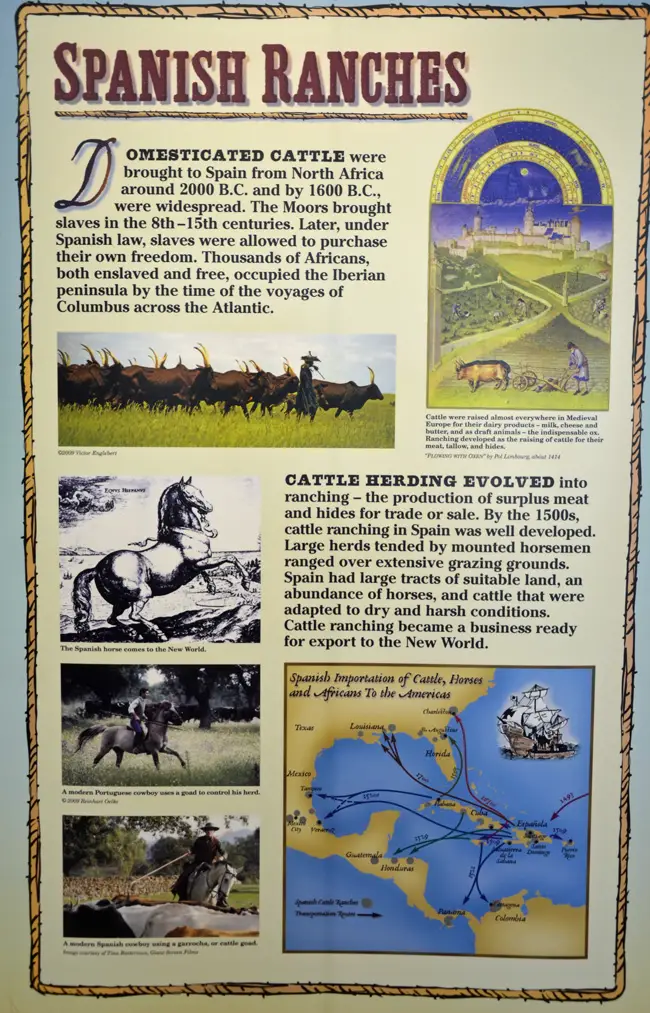

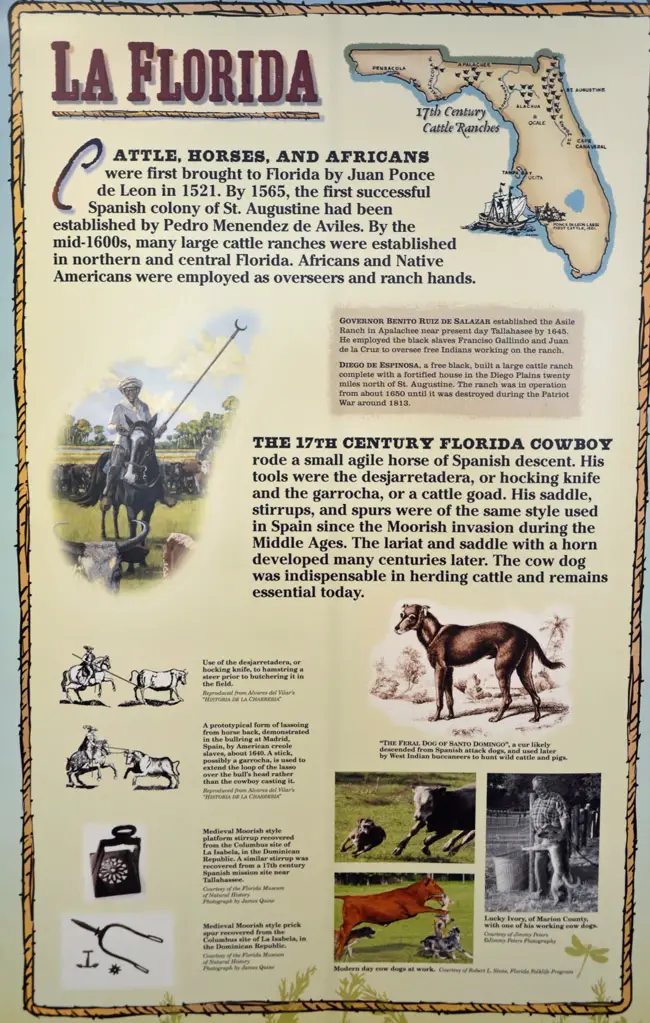

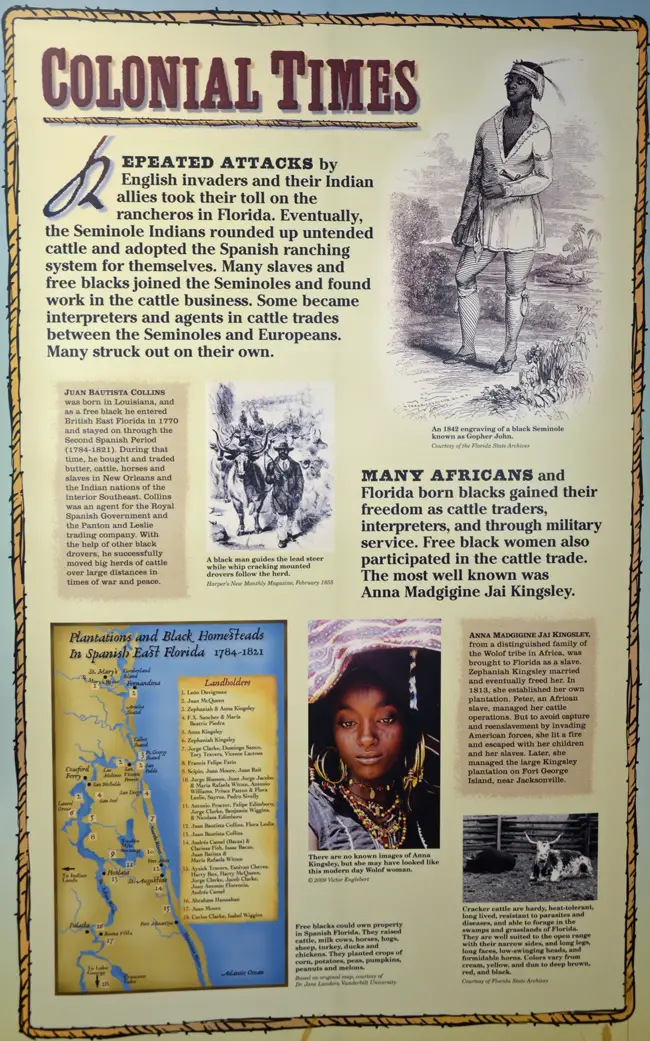

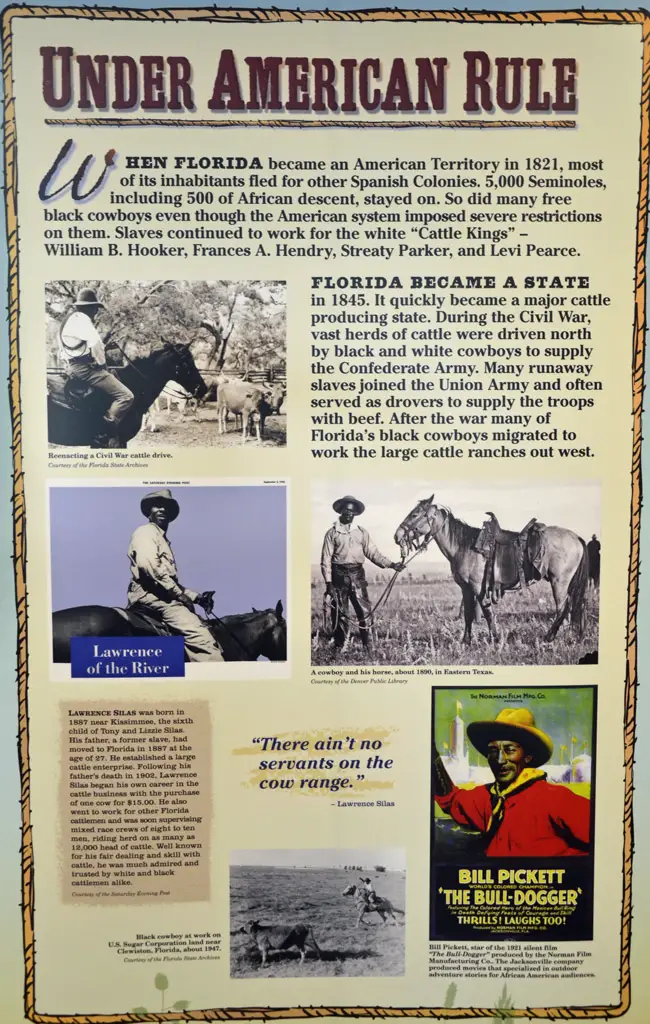

The exhibit is arranged simply as six colorful panels, the first one starting with the origin of cattle herding in Africa and the origin of the word cowboy (though its coinage, said to be from the Carolinas and explained as “a black slave who tended cows,” is not quite accurate). Another panel tells the story of Spanish ranches, then Ponce de Leon’s introduction of cattle—and, not so coincidentally, of blacks—to Florida in 1521.

The panels then take the story through Florida’s statehood in 1845, when the state became an important part of the ranching industry, and to the present, with some 20 portraits of modern-day black cowboys, including Rudy Bradley, who served in the Florida House of Representatives, and Woodrow “Big Boy” Mitchum, who still runs a ranch with some 500 heads of cattle near Chiefland.

Chester Trahan, a member of Flagler’s African American Mentor Program and an avid reader—he held in his hand “The Destruction of Black Civilization,” the book by Chancellor Williams—was among the guests at the opening of the exhibit. Much of history in the past has been told from an incomplete perspective, he said, which tended to perpetuate white superiority (such as in the scrubbing from popular history of the presence of black cowboys). “It doesn’t always conform with history,” Trahan said. “Sometimes the people who maintain that position kind of twist themselves into a pretzel trying to portray the idea that white people never did nothing before white people taught them how to do it. I mean, let’s be open about it, that’s a fact.”

Earl Johnson, principal at Matanzas High School, was grateful to see his school chosen as the first stop for the exhibit. “I think it will give students an understanding that there were black cowboys,” he said.

“We’re very blessed in Flagler County to have the state Florida Agricultural Museum right here in our backyard,” Oliva, the superintendent, had said in his welcoming remarks. “And I think historically we’ve done some events and some partnerships with them, but part of our vision was to take that to a different degree or different level, so when we have an opportunity to solidify a partnership such as the one we’re getting ready to unveil today, it’s a win-win, not only for our community and our county to have an exhibit like this, but for our students.”

The exhibit is scheduled to tour all nine Flagler County Public Schools through the end of the school year in June. The schedule is as follows:

Matanzas High School 2/1-2/12

Old Kings Elementary School 2/12-2/26

Flagler Palm Coast High School 2/26-3/11

Bunnell Elementary School 3/11-4/1

Rymfire Elementary School 4/1-4/15

Buddy Taylor Middle School 4/15-4/29

Wadsworth Elementary School 4/29-5/6

Belle Terre Elementary School 5/6-5/20

Indian Trails Middle School 5/20-6/3

The exhibit is below.

![]()

fredrick says

Very good article. To bad Cam Newton could not break a stereo type in his post game interview. But no, his attitude and hoodie fed into the racist stereo type of a thug in a hoodie. What a shame.

Layla says

Absolutely love this! Thanks, FL. Great story.

Heading North says

Flagler Live

What a fantastic tour through history! I never dreamt there were as many black cowboys, especially in Florida!

Excellent article – my compliments!