By Barry C. Burden

Over the past four years, Congress and state governments have worked hard to prevent the aftermath of the 2024 election from descending into the chaos and threats to democracy that occurred around the 2020 U.S. presidential election.

A new federal law cleaned up ambiguities that could allow for election subversion. New state laws have been enacted across the country to protect election workers from threats and harassment. Technology experts are working to confront misinformation campaigns and vulnerabilities in election systems.

But untouched in all of these improvements is the underlying structure of presidential elections – the Electoral College.

Here is a quick refresher about how the system works today:

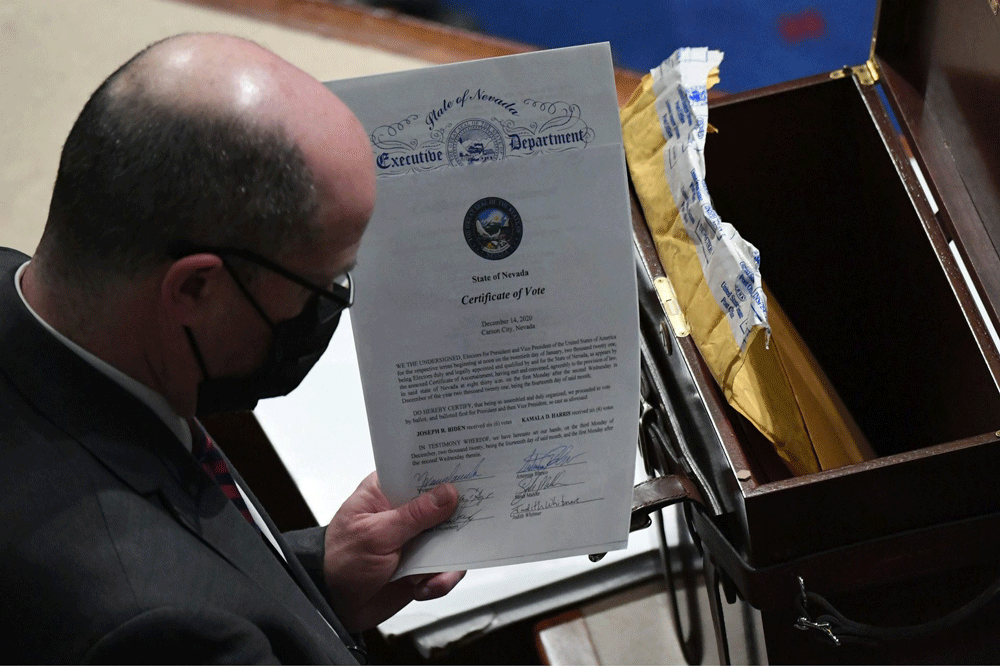

After citizens vote in the presidential election in November, the Constitution assigns the task of choosing the president and vice president to electors. Electors are allocated based on the number of congressional representatives and senators from each state. The electors meet in their separate state capitals in December to cast their votes. The ballots are then counted by the vice president in front of members of Congress on Jan. 6 to determine which ticket has won a majority.

The widely varied pros and cons of the Electoral College have already been aired and debated extensively. But there is another problem that few have recognized: The Electoral College makes American democracy more vulnerable to people with malicious intent.

A state-centric system

The original brilliance of the Electoral College has become one of its prime weaknesses. The unusual system was devised at the Constitutional Convention in 1787 as a compromise that prioritized the representation of state interests. This focus helped win over reluctant delegates who feared that the most populous states would disregard small states’ concerns.

Nowadays nearly every state has chosen to award all of its electoral votes to whichever ticket wins more votes in the state. Even if a candidate gets 51% of the popular vote, use of the winner-take-all rule in these states means they will be awarded 100% of the electoral votes.

This is what leads to the “battleground state” phenomenon: Presidential candidates focus their rallies, advertisements and outreach efforts on the few states where campaigns could actually tip the balance. In 2020, 77% of all campaign ads ran in just six states that were home to only 21% of the nation’s population.

In this way, the Electoral College system naturally draws campaign attention to issues that might tip the balance in these hotbeds of competitiveness.

Morry Gash-Pool/Getty Images

A road map for bad behavior

By doing so, the system essentially identifies the states where malicious people who want to alter or undermine the election results should focus their energies. The handful of battleground states are efficient targets for harmful efforts that would otherwise not have much success meddling in elections.

Someone who wants to infiltrate the election system would have difficulty causing problems in a national popular vote because it is decided by thousands of disconnected local jurisdictions. In contrast, the Electoral College makes it convenient to sow mischief by only meddling in a few states widely seen as decisive.

In 2020, the lawsuits, hacking, alternative electors, recount efforts and other challenges did not target states perceived by some to have weaker security because they had less strict voter ID laws or voter signature requirements. Opponents of the results also did not go after states such as California and Texas that account for a large share of the country’s voters.

Rather, all of the firepower was trained on about a half-dozen swing states. By one account, there were 82 lawsuits filed in the days after the 2020 presidential election, 77 of which targeted six swing states. The “fake elector” schemes in which supporters of Donald Trump put forward unofficial lists of electors occurred in only seven battleground states.

The popular vote alternative

A majority of Americans say in surveys they prefer to scrap the Electoral College system and simply award the presidency to the person who gets the most votes nationwide.

Dumping the Electoral College would have a variety of consequences, but it would immediately remove opportunities for disrupting elections via battleground states. A close election in Arizona or Pennsylvania would no longer provide leverage for upending the national result.

Any election system that does not rely on states as the puzzle pieces for deciding elections would remove opportunities like these. It could also seriously reduce disputes over recounts and suspicion about late-night ballot counts, long lines and malfunctioning voting machines because those local concerns would be swamped by the national vote totals.

Although not without its own concerns, an agreement among the states to award their electoral votes to the winner of the popular vote is probably the most viable method for shifting to the popular vote, in part because it does not require passing an amendment to the Constitution.

There is no ideal way to run a presidential election. The Electoral College has survived in its current form for almost two centuries, a remarkable run for democracy. But in an era where intense scrutiny of just a few states is the norm, the system also lights the way for those who would harm democracy.

![]()

Barry C. Burden is Professor of Political Science and Director of the Elections Research Center at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

coyote says

Here’s a cut-and-paste of a comment I posted after the 2012 Presidential elections. Upon a quick check at Wikipedia, it still appears to be valid :

======================================

Here’s a fact about the Electoral College that should give you reason for concern :

In all of the States in the United States – with the exception of two (Maine and Nebraska) – the votes of the Electoral College are awarded on a ‘winner take all’ basis – and NOT apportioned out in the ratio of the popular vote. This means that in 48 states, the party candidate who obtains the LARGEST vote of the popular vote (no matter what the actual percentage is) gets ALL of the Electoral votes, and the other party/parties voters are effectively disenfranchised.

So, if a state has, say, 20 electoral votes, and 40% of that states’ voters vote for the Republican candidate, 35% vote Democratic, and 25% vote for other parties, ALL 20 electoral votes go to the Republican candidate, and the other parties’ voters have just lost their votes.

This is why many of the states are considered “major” for a Presidential election. By having the highest vote count of the votes in just these “major” states – regardless of the actual percentage of the popular vote – a Presidential candidate is assured of winning the Presidency by garnering the total of the Electoral votes of those states – no matter what the popular vote count or ratio may be.

In actuality, a third-party candidate can REDUCE the number of popular votes which a candidate needs to win the entire Electoral vote of a state, and can, in essence, disenfranchise more voters in the state than just having two parties would –

i.e. a three-way almost tie – 33% vs 33% vs 34% – would give the Electoral votes to the party which received 34% of the votes – and disenfranchise 66% of the voters, whereas a two-party election can disenfranchise at most 49% of the voters. And it gets potentially worse as you add candidates. With four parties vying for President, then winner of all the Electoral votes may have as little as 26% of the popular vote – so long as it is the largest percentage of the popular vote.

Which is still a slap in the face no matter how many people get slapped. The ratios of the Electoral College votes of a state *should* be representative of the popular vote – not the ‘winner takes all’.

Think about it when you vote this year. The method of awarding the Electoral College votes can be changed by state – but the people (legislators) of each state who would have to do the changing have an embedded interest in maintaining the current system.

============================================

melly says

Then make everyone do apportionment. Making apportionment uniform between all the states maintains the EC system and makes it uniform. Problem solved.

This does not solve the separate problem of people voting who should not, or ballots being counted which should not be counted, for any number of valid reasons. It addresses the EC,period. The author makes it a standalone subject, therefore so do I..

tulip says

An election should be won by the candidate who got the most votes, period. The electoral college should go away.

jake says

Then this country would be run by nothing but California or NY radicals. Thanks, but no thanks. The electoral college is the only thing that keeps this country somewhat neutral.

“The Founding Fathers established the Electoral College in the Constitution, in part, as a compromise between the election of the President by a vote in Congress and election of the President by a popular vote of qualified citizens.”

This is a republic, not a democracy.

Pierre Tristam says

“This is a republic…” the line that gave the John Birch Society’s zealots something to say that didn’t sound demented, and still they get it wrong.

Ray W. says

Hello Jake.

Please consider the idea that you are spreading a partial truth.

Yes, America under the Constitution is in part a republic. And it is also in part a democracy. And it is also in part an expression of the idea of liberalism, which motivated our founding fathers, as diverse as they were, to engage in an experiment that is most accurately called a liberal democratic Constitution republic.

It has long been, of course, possible for a person to be right and wrong at the same time. You are the most recent example of that maxim. Please strive to do better on this subject matter.

Laurel says

Jake: China is a republic, not a democracy.

tulip says

if an election was decided by who won the most votes, there wouldn’t be swing states. battleground states, etc because every single vote in the entire country would count. I candidated A received 80 million votes and candidate B received 75 million votes that means Candidate won the election by popular vote, not a configured electoral votes decided by number of residents in state. So many people now move around the country so much and live in several different states over their lifetime that some states which had more Dems, now have more Reps and vice versa and the independent group has grown immensely thus it should be what the majority of people want, just like in other races that we vote in

Sherry says

Thank you Tulip. . . I couldn’t agree more!