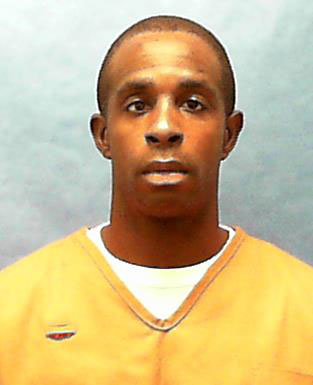

Cornelius Baker has spent the last 12 of his 33 years in jail or prison for the kidnapping and murder of Elizabeth Uptagrafft in the Mondex woods in 2007. In 2008 Circuit Judge Kim Hammond sentenced him to die. But like 200 other defendants on Death Row, Baker got a reprieve in 2016 when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the 9-3 jury recommendation for death Hammond ratified was unconstitutional. It had to be unanimous.

Just like David Snelgrove, a fellow-Death Row inmate from Flagler County whose penalty phase got re-tried for the same reason in the past seven days, and got a jury to commute his death sentence to life in prison on Tuesday, Baker now has the same opportunity. He’s scheduled for trial toward the end of February, when a jury will decide whether to recommend death (again) or commute his penalty to life in prison without parole. There would be no other choices. His guilt and conviction are not in question.

He was due in court today for a pre-trial, part of the crucial steps before trial when lawyers on both sides frame the case through numerous motions, some of which could prove key in a successful defense–just as some of them could prove key in the prosecution’s case, depending on which way the judge rules.

Baker chose not to show up. And his lawyer, Junior Barrett, somehow didn’t know that his client had begged off, that Baker had waived his appearance months ago, signalling–intentionally or not–that his presence at one of the hearings that will decide his fate just wasn’t that important. (Snelgrove much earlier in the process had done the same thing, in one case because he had a dental appointment that had been more difficult to secure than a court date, to get fitted for new teeth, and he didn’t want to miss it: the Department of Corrections is not especially accommodating to its wards.)

“For certain hearings he’s required to be here,” Barrett told Circuit Judge Margaret Hudson.

“So we need to get this continued one more time,” she said, and did: the pre-trial was reset for Feb. 4.

The lawyers didn’t want today’s hearing to be entirely wasted, so they handled it as a status hearing, where a defendant’s presence isn’t required, though what was “status” turned into more of a pre-trial anyway as Hudson and Barrett wrangled a bit over a request on his part: he wants to submit a seven-page questionnaire on the death penalty to potential jurors, during jury selection.

But not 14 questions spread over a seven-page document that includes a voluble two-page preface with occasionally tendentious writing (“Please do not give ‘politically correct’ answers or what you think the court or lawyers want to hear”) or the sort of characterization that would not help either side’s lawyers (he describes the jury-selection process as potentially “tiresome”), or repeated claims that the questions are intended to “save time.”

The questions themselves are relatively straight-forward questions that could appear on a Gallup poll on the subject: “Do you think the death penalty in the United States is used too often, about right, or too seldom?” “Do you believe in the concept of ‘an eye for an eye’ and ‘a life for a life’ with respect to the death penalty as punishment for intentional murder?” “Do you believe that background information about a defendant is something relevant to the jury’s consideration of penalty,” with the three choices being “probably,” “possibly” and “unsure.” The defense in penalty-phase trials relies overwhelmingly on the defendant’s background to make the case for “mitigators” and convince the jury that death is not called for.

Hudson didn’t need to see the questions to know that Barrett was going down the wrong path. “An eight-page questionnaire is not what I had in mind. I’m talking about one page, whatever you can limit to one page,” Hudson said. “We’re not going to have an eight-page document we’re going to be flipping through.” She said a long questionnaire would mean the reams would have to be filled out and analyzed before they could be useful, a process that could take hours by itself though many of the questions could be answered during the oral question-and-answer periods of jury selection (known as “voir dire,” a French phrase derived from the Latin for “saying the truth”). Hudson told Barrett that his preface was unnecessary and his questions better phrased for yes or no answers. “Nothing but questions,” she said. “It should be very self-explanatory questions.”

“I can’t see from the defense’s side one page working,” Barrett said. “I’m not sure how many real questions can be fit to one page.”

“Believe me you’re going to get better answers that way instead of asking for essay type answers,” Hudson said of the yes or no format.

“I disagree, judge,” the occasionally irascible Barrett said, though he’d lost the battle. The judge reminded him that the ultimate answers won’t be provided by written answers anyway. Three groups of 50 potential jurors each are being called in for the trial. The large pool is required because of the nature of the responsibility: anyone who opposes the death penalty, or who who may support it but would not impose it, will be automatically excused, though neither the defense nor the prosecution want dogmatists from either side, either.

In the end Hudson left the door open for a two-page questionnaire, front and back, and prepared an order to require Baker to be present at 11 a.m. on Feb. 4. The case is being prosecuted by Assistant State Attorneys Jason Lewis and Tammy Jaques.

The original questionnaire Barrett had proposed is below. It will be substantially different when presented to potential jurors.

![]()

Steve says

Keep him locked up. Whatever. No show in life