By Andrew Dix

In his book On Late Style, published posthumously in 2006, the Palestinian American critic Edward Said identifies a striking characteristic of some writers as they near the end of their lives.

Rather than going gently into that good night, to borrow poet Dylan Thomas’s phrase, they exhibit instead “a renewed, almost youthful energy”. In Said’s account, the work of these aged writers communicates not “harmony and resolution”, but, rather, a sense of “intransigence, difficulty, and unresolved contradiction”.

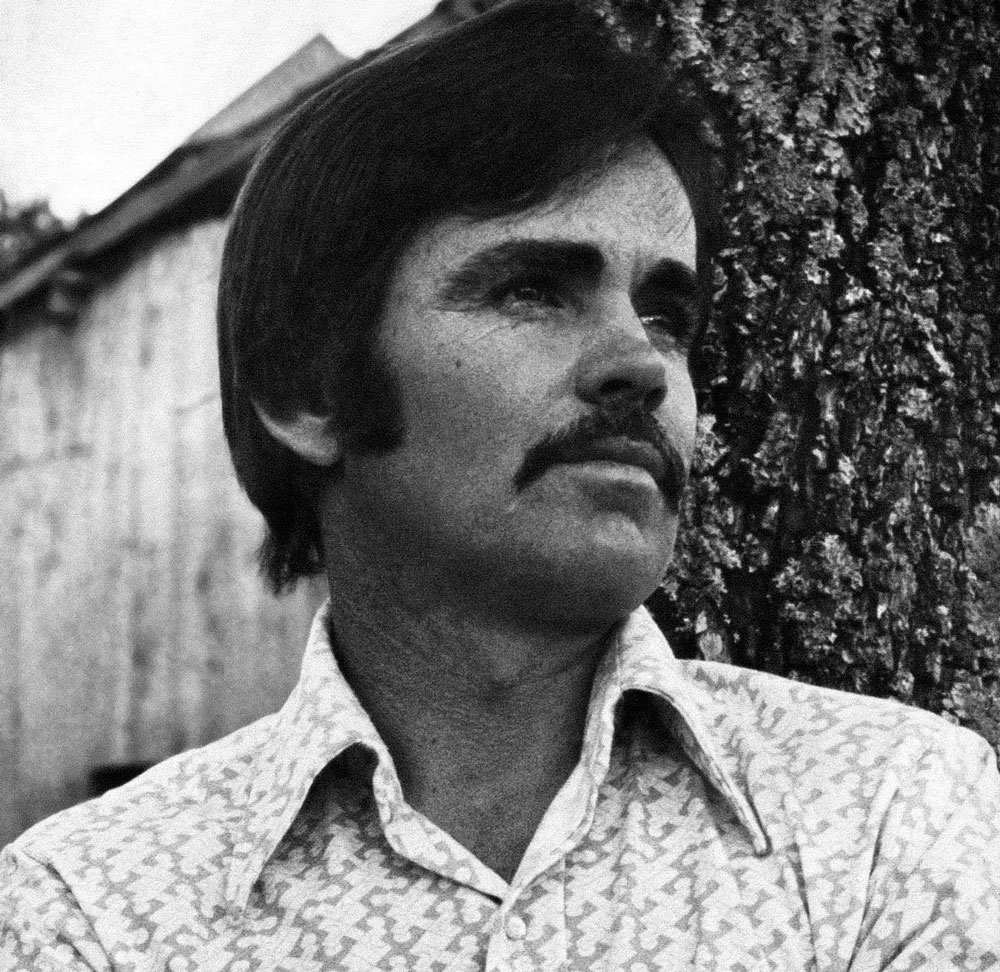

The late styles of writers are nevertheless liable to vary. The three novels that the American writer Don DeLillo has published since 2010, for example, practise extreme compression and challenge the reader by just how reduced they are. In contrast, the latest novel by DeLillo’s 89-year-old compatriot Cormac McCarthy is marked by the commitment to excess and open-endedness of which Said speaks.

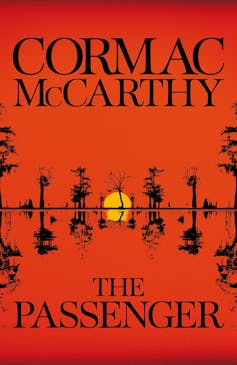

The Passenger is McCarthy’s 11th novel in a fiction-writing career that began in 1965 with The Orchard Keeper, his first foray into the tradition of southern gothic.

A 12th, Stella Maris, will appear very soon, reimagining characters and plots from The Passenger. While the qualities of Stella Maris remain to be seen, The Passenger is a rich novel that should appeal to readers both familiar with McCarthy and new to his work.

‘A level of dishevelment … we’ve not seen before’

The American critic Fredric Jameson reminds us, in a recent piece in the London Review of Books, that “novels are put together out of all kinds of raw material; they don’t really have the purity of the older genres”. He proposes that in approaching novels we set aside thoughts of “linear narrative”. Instead, he asks us to imagine “a pile of separate and uneven strata, geological layers, irregular laminates”.

Some novelists, of course, seek to resist this sense of slithering multiplicity and to present their fiction instead as a smoother, more orderly thing. By contrast, in The Passenger McCarthy seems determined to enjoy the novel form’s plurality. He welcomes into his text everything from bawdy puns to lyrical descriptions of landscapes and from shaggy dog stories to discourses on welding techniques.

At the outset, The Passenger, like McCarthy’s No Country for Old Men (2005) before it, seems destined to be a thriller. Its hero is Bobby Western, formerly a physics student and racing driver but now a salvage diver. Bobby comes across a submerged plane off the Louisiana coast from which the body of a passenger is inexplicably missing.

To this aquatic version of a locked room mystery, other elements of the thriller genre are added: stolen letters, a cache of gold coins and investigators with a faintly menacing air. For a while, the reader, like Bobby, sifts for clues and follows leads.

Yet the motifs of the thriller give way to other sorts of “raw material,” to reuse Jameson’s terminology.

For a start, The Passenger increasingly substitutes leisurely talk for propulsive action. Characters discourse at length in New Orleans bars about the Kennedy assassination or the Vietnam War or advanced physics.

But The Passenger also draws away from unexplained things in the outside world to trace instead Bobby’s feelings for his sister Alicia, a maths prodigy who was fatally drawn to “a blackness without name or measure”. Suspense and science, punning and lyricism, hallucination and incest: the novel splices these and other strands together, generating what Said calls the “non-harmonious, non-serene tension” typical of a writer’s late style.

‘Everything vanishing as if it had never been’

In common with McCarthy’s previous fiction, including its immediate predecessor The Road (2006) and the apocalyptic western, Blood Meridian (1985), The Passenger is preoccupied with death. Individual deaths (notably Alicia’s), collective deaths (“these people would be stricken from the register of the world”) and cosmic deaths (God “will wet his thumb and lean over and unscrew the sun”).

Given McCarthy’s advanced age, it might therefore be tempting to see this novel as ultimately one of termination, expressing a dying of the light (to quote Dylan Thomas again). Such a reading is supported by the book’s many echoes of McCarthy’s previous fiction as if what we have in front of us now is summing things up. As if it is the writer’s last testament.

Yet The Passenger is a book of life and liveliness. The novel’s language communicates energy, not entropy – a sense of opening up, not winding down. At its most localised, this verbal exuberance runs through individual lexical choices. There seems no word that McCarthy doesn’t know and he fans life into archaic or obscure terminology (eskers, kedge, lemniscate, uncottered and many more).

At the level of sentence design, too, McCarthy continues to experiment with syntax and punctuation and rhythm. Here’s just one sentence, conjoining the blackest insight and the brightest creativity:

Host and sorrow to waste as one without distinction until the wretched coagulant is shoveled into the ground at last and the rain primes the stones for fresh tragedies.

Even as McCarthy writes in old age about death, he continues to do so from a state of rude literary health.

![]()

Andrew Dix is Lecturer in American Studies, Loughborough University.

Leave a Reply