This is the story of the Colleen Conklin you do not know.

This is the Conklin before the Conklin you came to know, before today’s longest-serving elected official (in consecutive years) started the quarter century on the Flagler County School Board that ends next week.

This is the Conklin with family roots in Belfast, with professional roots in Harlem and the Bronx and of course in Flagler Beach long before she tormented Superintendent Bob Williams with phone calls every morning her first months as a board member in 2000 and 2001, when she was a “bull in a china shop” out to change a district.

This is the Conklin who grew up in back of her parents’ bars, the Conklin who drove trucks, started her teaching career in the South Bronx, founded human rights chapters, conquered learning obstacles all the way to a doctorate but also nearly dropped out of college to veer into a career in insurance but for her fortunate firing by a boss who knew better than to smother her gift, which was not in insurance.

As Conklin is celebrated later today by the School district she served so long, and as she steps down next week after her last workshop, the focus will be on those 24 years, on her championing of students and employees, on her advocacy for the less privileged and more challenged, on the fires she lit in defense of free expression and the arts, of the less conventional, the uncommon and the bullied.

Where did all this come from? How could she possibly manage it all through a life rarely short of its own struggles until now largely unknown to most? They were the very struggles that sourced an unusual fount of empathy and made her the broad-minded and irrepressible board member she became, especially in the second part of her career as her political and parliamentary skills made her permanent minority status on the board almost irrelevant. She went from idolizing certain heroes in her youth to becoming one to many, which makes her departure–at the height of her career and powers–as much a puzzle as a clue: there is a lot more to Conklin than her school board profile, and there is a lot more ahead. Her past explains both paths in many regards.

Conklin’s parents were born and raised in Ireland. Bridget Dewar and Thomas Walsh were both from Belfast, nearly from the same neighborhood. They’d never met there. They migrated to the United States separately, both to the Bronx. Walsh came over as a teen-age golden-glove boxer who’d end up fighting at Madison Square Garden in the late 40s or early 50s. Bridget came over much later.

They had married different people, had children and separate lives, difficult marriages but for this: Thomas (who was married to a teetotaler) and Bridget would end up at the same Irish dances together. Before long, their own story began. Their relationship was as if born of a line from Irish novelist John McGahern: “They were excited, the intolerable vacuum of their own lives filled with speculation about the drama they already saw circling about this new wound.” They got married in St. Augustine.

Colleen, “the first Yank,” was born in New York. She would be their only child, though her family tree of half-siblings from those former marriages casts shadows across continents, including a sister in Palm Coast. Her parents owned bars in Rockland County, just north of New York City–the Jolly Sixpence, the Minstrel Boy and Molly Maguires. “My playpen was the back of a bar,” Conklin says. The marriage was as stormy as the Irish Sea, so the family moved almost every two years between Flagler County and New York, the first move dating back to 1975, when Colleen was barely 7.

“I was that kid that every time my school records caught up with me, we were gone,” she said. She attended Bunnell Elementary, the school where she would end up teaching, and eventually attended Flagler Palm Coast High School for 7th and 8th grade (“once a Bulldog, always a Bulldog!” she says). Her parents had bought the Harbor Inn, the bar under the old Flagler Beach bridge, renaming it the Bridge Tender. “My job as a 7, 8 year old, was to run up to the bridge tender at the time, sometimes he’d fall asleep,” she said. That was back when the bridge had to be raised to let vessels pass. “I never knew his name.” She’d yell: “Mr. Bridge Tender, open the bridge!”

Then it was back to New York. She graduated from Ramapo High School in Spring Valley, N.Y., in 1986. College didn’t seem to be in the cards. Early in her schooling she’d surmounted significant learning obstacles, though she wouldn’t learn the extent of those obstacles until much later. Colleen had no idea how to go about applying for college. Her SAT scores were “horrific.” Her mother was “of the mindset to get a freaking job. You know: you’re on your own.” Colleen had a job: by then her father owned a trucking business, Emerald Trucking. She drove his trucks to Boston and back. She took care of the books. She knew what kind of money there was in it. She was prepared to take over the business.

But Colleen’s girlfriend Tracy Dylan was going to St. Thomas Aquinas College in Spark Hill, her English teacher Mrs. Murphy–an ex-nun–was encouraging her to join her, so was her father, who was big on education though he’d not gotten past 6th grade. She didn’t apply until June that year, six months later than when colleges take applications (there’s a running theme in Conklin’s life: promptness is not it.) She was in Florida when she got the call in August. Miracle of miracles: A late admission. She was in.

Conklin still thought she’d take over Emerald Trucking, so she started a business major. “I hated it,” she said. “I got statistics, and I was like: this is miserable. I do not want to do this.” She took an education course with Thomas Kaiser, a legend at that school. It was about education equity. “I was sold,” she says, though not entirely. Nearing her senior year she was going to school full time and working almost full time at Allstate, the insurer, she had her own apartment, was paying her own bills. A full-time position opened. Great money. “My dad was like, we’re not having this conversation. You’re finishing school, and that’s the end of it,” she said. She went to work that Monday ready to take the job.

Her boss, Wade Winter, who’d hired her, fired her.

“I was like, What? What? He’s like, you’re fired. You need to go to school full time.” Winter was among those tough-love people who redirected Conklin’s trajectory just at the right time. “He was a mentor to me. He was just like, listen to me. You’re never going to get these years back, ever. You need to just fully commit. Go back to school full time, bang it out, get it over and done with. You have a gift. When you’re ready and you get your degree, I promise you, I will hire you.” There would be a few others like Winter along Conklin’s path, among them Jim Guines on the school board.

She never went back. As she was graduating she was hugely influenced by Savage Inequalities, the Jonathan Kozol book that revealed disparities in schools along racial and class lines. She’d started a chapter of Amnesty International, the human rights organization, on campus. The day of her graduation–by which time she was a Kelly girl, working in that temp agency for whatever she could get–she was offered a job as a congressional aide in Washington, D.C., in the office of Republican Congressman Benjamin Gilman of Poughkeepsie (she’d spent a summer internship in Congress, working on a human rights committee), and she was offered a job teaching first grade in the South Bronx.

Glamor and power on one side, an unglamorous assignment in one of the roughest neighborhoods in America on the other.

Guess which she took.

Conklin would be her own Kozol. Her parents after all had been politically, passionately engaged. They’d insisted that their daughter would be so as well. “I was raised going to protests,” she remembers, “anything related to Northern Ireland. I would say my activist roots came from that fire, the fire in the belly, about just a united Ireland. And that very much stuck with me, how the Catholics were really oppressed people, no access to housing, no jobs, and all the rest of that.” Bernadette Devlin , the Irish civil rights leader and politician, was a hero. Mother Teresa was another. Conklin loved Devlin’s take-no-prisoner fire, loved Mother Teresa’s idea of service, two poles of activism that would magnetize Conklin’s career.

The school was in Hunts Point by Yankee Stadium, well before the Bronx renaissance. She would commute daily on the Major Deegan Expressway from Rockland County to an annex of J.H.S. 151, Lou Gehrig Middle School, an old woodshop room with cardboard covering the windows. She had 32 first graders. Their first language was Spanish. All of them. Eight were wards of New York’s equivalent of the Department of Children and Families. It was neither the safest nor the most inspiring environment. But that’s what Conklin had sought out.

“I got propositioned in the hallway by the middle school student,” she said. “I informed him that he would be singing soprano for the rest of his life if he ever put a finger on me again. Kind of took care of that. But all the kids that would hang out at the end of my hallway and smoke pot, I ended up recruiting all of them into my classroom as aides and working it out so they got middle school credit.”

From there it was to P.S. 5, one of the first brand new schools in New York City, at the end of Dyckman Street and Harlem River Drive in Manhattan, ironically where her dad had spent his youth when Dyckman Street was an Irish neighborhood: she remembered him taking her there when she was a child. (It’s now Spanish Harlem.) There she developed close bonds with her students. “Those kids were my world,” Conklin says. “I spent weekends with them, took them places and did things, but they were a real, big, big part of my life, and we still stay in touch.” Out of 36 students, 20 have reconnected on Facebook. Some of them attended her wedding. They still have periodic reunions.

She was still spending summers in Flagler Beach. Her goal at the time had been to be the city’s youngest principal. (She got her master’s degree from famed City College in 1998.) But she had second thoughts. She didn’t want a stranger raising her children, and as an administrator she’d have to leave the house at dawn and not come back until nightfall. “Everything changes when you become a mom,” she says.

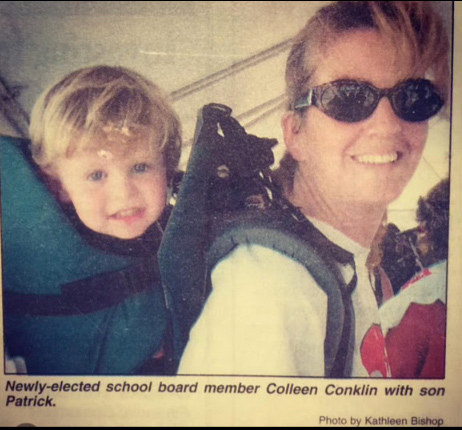

She got married, was pregnant in her last year teaching, and left New York in a Penske rental with her husband Chris and everything they owned, buying the house next to her parents in Flagler Beach. That was in April 1997. (They almost bought a house in Grand Haven, but at the signing, Conklin balked: she hadn’t come down to Florida to be house poor, she said.) Her son Patrick was born in June.

She had her JFK-Democrat parents on one side and her Republican in-laws on the other, two radically different sets, with her in between. In her childhood she’d learned the art of debate in a house noisy with arguments and fury. She was now unwittingly learning the art of arbitrating, an affinity for seeking consensus that would serve her so well later on. “Literally, our Sunday dinners before reality TV–if I had only thought to put a video camera,” she recalls.

Her then-husband Chris had a successful painting business in New York. The idea was to continue that in Flagler Beach while she would be a stay-home mom. Chris “busted his ass” but they struggled, especially against the still-engrained local prejudice that favored local businesses: The Conklins were identified with New Yorkers, and New Yorkers got passed over when a contract could go to a local. She took a teaching job at Bunnell Elementary.

After her second son, Ryan, was born, the family was sitting around the table discussing where the children would go to school. “Everyone was talking about private school,” Conklin remembered. “I was like: We’re not doing that. I’m a public school teacher. What are you talking about? And it was my dad, he was just like: Well, you’re the one that’s always complaining about how behind the district is, why don’t you do something about it?” The idea born then and there would be like Conklin’s third child: her school board career.

At the time her own principal, Larry Kondas, was running for School Board, as were Anita Gustafson, John Moylan (the late father of Assistant County Attorney Sean Moylan), and Mark Palmer. “I don’t know what I was thinking, but I was like, I’ll throw my name in the hat,” Conklin said. The primary election was on Sept. 5. She joined the race at the end of June, right before the end of qualifying. Kondas told her if she changed her mind, she was welcome to work on his campaign.

“That was all I needed,” she said. The Conklin fire was lit again.

She didn’t think she’d win. She just wanted to shine a light on specific issues: salaries near the bottom of Florida’s 67 districts, outdated textbooks, zero technology. She knocked on one door, with one of her young children in tow. A man in his underwear answered–and asked her in. That was it for door-knocking: she was so “creeped out” that she never did it again the rest of her career. She campaigned outside the Winn-Dixie on State Road 100.

She didn’t just win, outpolling Kondas, the second-leading vote getter, by nearly 2-to-1, but she won every single precinct, as she would in every election hence, except he last one, when she lost three precincts (out of about 26).

“I called poor Bob Williams up every single morning,” Conklin said, referring to the superintendent at the time. “Leslie Anderson was the admin for the superintendent at the time. Because I didn’t know: I called Bob every single morning and be like: What can I do today for you? What would you like me to do? I’d just come out of the classroom, it was like, we got things to do. We got we got things to change. Every. Single. Morning.”

Anderson would laugh at her, and at times would tell her: you don’t need to do that. It’s OK. “I didn’t learn how to count to three until, like, the third year. I was really kind of like a bull in a china shop. It was like, All right, let’s get things done. Let’s move, let’s go, let’s do what we got to do, you know? I learned a lot in the very short period of time.” To this day when she runs into Bob Williams, she begs his forgiveness. She’d learned by the time Bob Corley came along not to do that. Corley was the superintendent between Williams and Bill Delbrugge. Not a good time. Not a good time at all. The board buckled and frayed from Corley’s strange and erratic leadership until he was forced out. It was one of those key experiences in Conklin’s formation in the politics and intrigues of large organizations.

Her experience with Jim Guines was another. “I remember Dr. Guines and I in the beginning,” she said of the board member who’d end up serving 11 years before his resignation for health issues in 2007. “He was hard on me. He was really tough. But I wanted his approval so bad. Do you know that kind of relationship? I respected his background, I respected who he was as a person, but God, he was a ballbuster, and I was going to give it right back to him as much as he was going to give it to me. We had this relationship where it was like: Listen, kid, you’re going to learn. You’re going to learn the hard way, because you’re too big-headed to learn the easy way. So you’re going to go through the fire with me, and you’re going to learn. And I really did, I learned so much from him.”

Conklin and Guines railed at each other at times. But she sought his approval, grew thanks to him and learned from him. “He was hard, he was tough on me, but I always felt like it was coming from a place of love, and he wanted me to learn. And sometimes, you know, the greatest growth comes through pain, that is the truth. I don’t care what it’s about or what the topic is. I adored, really, out of all the board members that I’ve ever worked with, Jim Guines was probably the most meaningful relationship, both personally and professionally, that I had in my lifetime, because he stretched you. He stretched you. He stretched you in a good way.”

The only other individuals she felt that way about–someone she wanted to make proud–other than her parent are John Winston and Phyllis Pearson, neither of whom likely realize the impact they’ve had on her.

The rest in Flagler is better-known history, though not nearly as well known as this: since her days in primary school Conklin had been a student who’d “always struggled with different math, paying attention, processing different things.” Even reading had been a challenge.

It would only be years later that she’d discover through a nuts-to-bolts diagnosis, when she was 37, that she was phonetically deaf and had a form of dysgraphia, which can affect written letters and numbers. “I remember when I sat down with the educational psychologist that did all the exams, and he’s like: I have no idea how in the world you have made it to where you are today. He said it’s just pure perseverance. And I cried when he went through everything. I just sobbed in his office.”

And from there, she went on to earn her doctorate a few years ago, underscoring to what extent she’d managed to conquer the difficulties. Finishing it was really about two things, she said: “My parents were Irish immigrants with a sixth-grade education, and I wanted that doctorate as much for them as I wanted it for me, to prove I was more than just what people saw, that I had a brain and intellect,” Conklin said. She also represented innumerable students in her shoes, facing similar learning difficulties that could nevertheless be overcome. She hasn’t stopped learning (she’s a constant reader, mostly through Audible, the audio app). She credits her mother: “My mom was tough on me but she made me believe I could do or be anything. She was my entire world.”

The last four years have been a cycle of shocks, some of them alluded to in Conklin’s social media pages, some of them not. As it is with many children who see their parents through adult eyes, through eyes that have known parenting, Conklin says the parents she moved next to those two and a half decades ago were very different from the parents who’d raised her. They’d mellowed. They had their own memories of struggles and sorrows and regrets, but the family had persevered and survived.

Then came the shocks. Her father-in-law Stanley Drescher, Flagler Beach’s poet laureate, died within days of her 52nd birthday in 2020. Her mother died in 2021, her father in 2023, her marriage ended. This year she had major, painful surgery to remove a tumor that proved benign. And of course she opted not to run again, ending that enormously significant part of her life and all the contacts that go with it, all the sense of immediacy and relevance that a prominent political position on a school board provides.

“Life has been a little nutty in the last four or five years,” she says. “I don’t actually know if I’ve grieved all that I’ve lost. You know, between my father in law, my mother, my father, my marriage. I just kind of feel like I’ve kind of put everything and everyone first. For the first time in my entire life, I’m trying to figure out me, and I don’t know what that looks like.”

She talks about the Peace Corps, a dream she’s had since her youth, or working on a farm somewhere. She’s launched a publishing company with her friend Heather Bevan (Turn the Page Publishing). She has a book in manuscript. She thinks about opening a pub on the west coast of Ireland, or “following my sons around the world as they surf.” (The Conklins have been a competitive surfing family for decades.) She talks workforce development, women empowerment, preparing students to navigate emerging technologies, working with the school district. She continues her work at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University, where she is the executive director of the Gaetz Aerospace Institute. At 56, she sounds as if everything until now was prelude.

“I’m just really looking forward to kind of rediscovering who I am and figuring out the next steps,” Conklin says. ” I do want to believe that public service is still an honorable thing to do. But I’ve gotten a little too close to see how the sausage is made, and you really almost have to sell your soul. And I don’t know if I’m willing to do that. But I still have the fire in the belly. I’m not ready to retire. But at the same time, I’m drawn back to that. If all the good and decent people say no, then what are we left with, right? And I’m no way saying like that I’m this person that could fit that bill. I’m flawed like any other human being. But I still believe in public service, and I still believe in just the overall goodness of people.”

–Pierre Tristam

![]()

Jan says

An inspiring, wonderful recap of a wonderful person. Thank you.

Michael J Cocchiola says

Colleen is the prototypical school board member by which I judge all candidates for this critical position in our community. She has been a steadfast supporter and advocate for our public school students and teachers. I have never met a more principled and driven civic leader anywhere.

We will all miss Colleen greatly. May her next great adventure be as exciting and fulfilling as her first.

me says

Thank you for your years of service to our community.

Chris Conklin says

what a great article. Colleen has been an amazing board member. always prepared and 100 % class. you can never replace the goat only hope to find someone half as good. it was a pleasure to have 1st row seats of an amazing journey.

Heather Beaven says

She’s remarkable in every way and Flagler is a much better place because two Irish immigrants decided to buy a little pub they called the Bridge Tender.

Brian says

Great article about an amazing woman

Merrill Shapiro says

It looks like there will be a special election to decide who will represent our community in the US House of Representatives. I, for one, strongly urge Colleen to run, run, run!! There couldn’t possibly be a finer public servant!

Haw Creek Girl says

Walshie….DO IT!!! 💗

Linda says

Beautiful story of a beautiful lady. Thanks very much for your service, Colleen.

Celia Pugliese says

Farewell and “Very Happy Trails to You” Colleen!

EllenK says

Colleen’s steadfast determination and passion to stay laser focused on the true needs of our students, families and community has lead our schools and county to great achievements.

Making decisions through reason and knowledge from continued research and experience, Colleen was able to make great strides through many obstacles and challenges. There’s no doubt that she will be greatly missed in her school board role but will continue to make the world a better place.