By Nadir Jeevanjee

Climate models are complex, just like the world they mirror. They simultaneously simulate the interacting, chaotic flow of Earth’s atmosphere and oceans, and they run on the world’s largest supercomputers.

Critiques of climate science, such as the report written for the Department of Energy by a panel in 2025, often point to this complexity to argue that these models are too uncertain to help us understand present-day warming or tell us anything useful about the future.

But the history of climate science tells a different story.

The earliest climate models made specific forecasts about global warming decades before those forecasts could be proved or disproved. And when the observations came in, the models were right. The forecasts weren’t just predictions of global average warming – they also predicted geographical patterns of warming that we see today.

Johan Nilsson/TT News Agency/AFP

These early predictions starting in the 1960s emanated largely out of a single, somewhat obscure government laboratory outside Princeton, New Jersey: the Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory. And many of the discoveries bear the fingerprints of one particularly prescient and persistent climate modeler, Syukuro Manabe, who was awarded the 2021 Nobel Prize in physics for his work.

Manabe’s models, based in the physics of the atmosphere and ocean, forecast the world we now see while also drawing a blueprint for today’s climate models and their ability to simulate our large-scale climate. While models have limitations, it is this track record of success that gives us confidence in interpreting the changes we’re seeing now, as well as predicting changes to come.

Forecast No. 1: Global warming from CO2

Manabe’s first assignment in the 1960s at the U.S. Weather Bureau, in a lab that would become the Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory, was to accurately model the greenhouse effect – to show how greenhouse gases trap radiant heat in Earth’s atmosphere. Since the oceans would freeze over without the greenhouse effect, this was a key first step in building any kind of credible climate model.

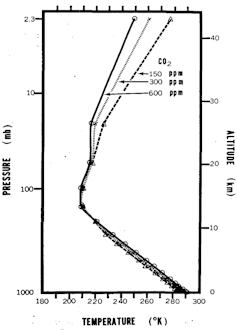

To test his calculations, Manabe created a very simple climate model. It represented the global atmosphere as a single column of air and included key components of climate, such as incoming sunlight, convection from thunderstorms, and his greenhouse effect model.

Syukuro Manabe and Richard Wetherald, 1967

Despite its simplicity, the model reproduced Earth’s overall climate quite well. Moreover, it showed that doubling carbon dioxide concentrations in the atmosphere would cause the planet to warm by about 5.4 degrees Fahrenheit (3 degrees Celsius).

This estimate of Earth’s climate sensitivity, published in 1967, has remained essentially unchanged in the many decades since and captures the overall magnitude of observed global warming. Right now the world is about halfway to doubling atmospheric carbon dioxide, and the global temperature has warmed by about 2.2 F (1.2 C) – right in the ballpark of what Manabe predicted.

Other greenhouses gases such as methane, as well as the ocean’s delayed response to global warming, also affect temperature rise, but the overall conclusion is unchanged: Manabe got Earth’s climate sensitivity about right.

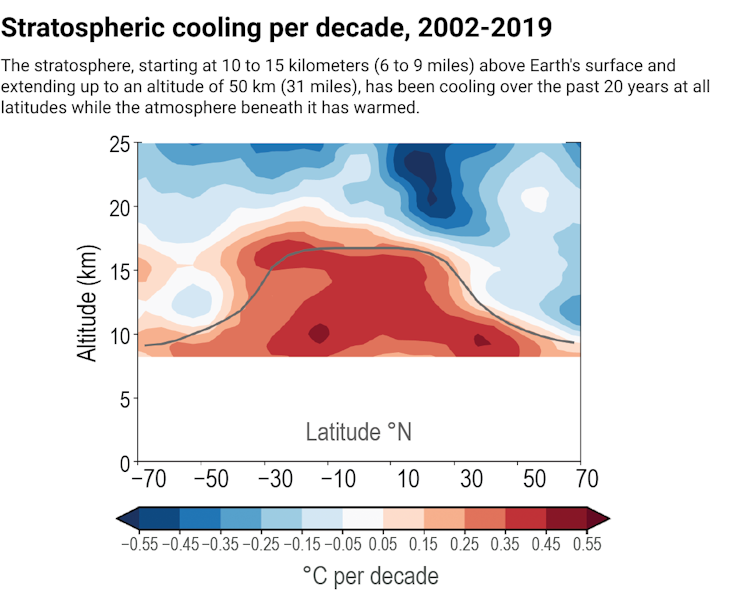

Forecast No. 2: Stratospheric cooling

The surface and lower atmosphere in Manabe’s single-column model warmed as carbon dioxide concentrations rose, but in what was a surprise at the time, the model’s stratosphere actually cooled.

Temperatures in this upper region of the atmosphere, between roughly 7.5 and 31 miles (12 and 50 km) in altitude, are governed by a delicate balance between the absorption of ultraviolet sunlight by ozone and release of radiant heat by carbon dioxide. Increase the carbon dioxide, and the atmosphere traps more radiant heat near the surface but actually releases more radiant heat from the stratosphere, causing it to cool.

This cooling of the stratosphere has been detected over decades of satellite measurements and is a distinctive fingerprint of carbon dioxide-driven warming, as warming from other causes such as changes in sunlight or El Niño cycles do not yield stratospheric cooling.

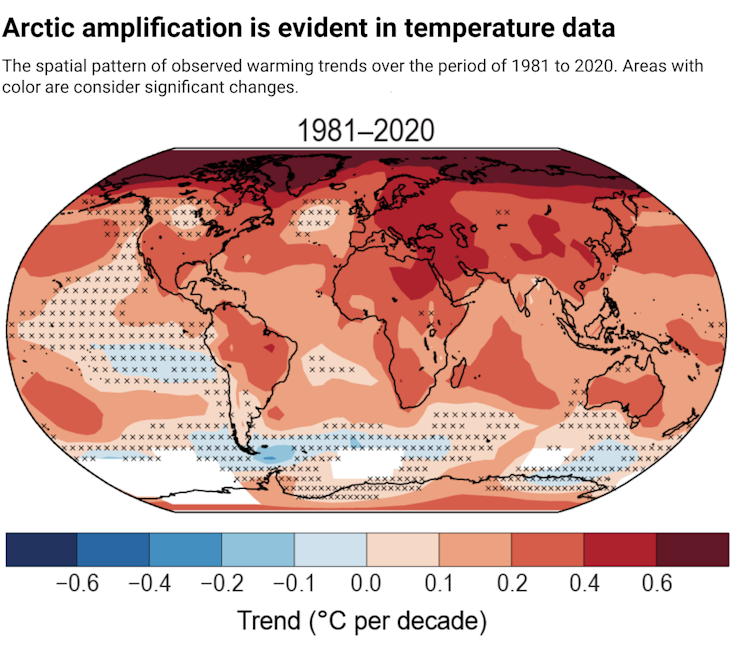

Forecast No. 3: Arctic amplification

Manabe used his single-column model as the basis for a prototype quasi-global model, which simulated only a fraction of the globe. It also simulated only the upper 100 meters or so of the ocean and neglected the effects of ocean currents.

In 1975, Manabe published global warming simulations with this quasi-global model and again found stratospheric cooling. But he also made a new discovery – that the Arctic warms significantly more than the rest of the globe, by a factor of two to three times.

This “Arctic amplification” turns out to be a robust feature of global warming, occurring in present-day observations and subsequent simulations. A warming Arctic furthermore means a decline in Arctic sea ice, which has become one of the most visible and dramatic indicators of a changing climate.

Forecast No. 4: Land-ocean contrast

In the early 1970s, Manabe was also working to couple his atmospheric model to a first-of-its-kind dynamical model of the full world ocean built by oceanographer Kirk Bryan.

Around 1990, Manabe and Bryan used this coupled atmosphere-ocean model to simulate global warming over realistic continental geography, including the effects of the full ocean circulation. This led to a slew of insights, including the observation that land generally warms more than ocean, by a factor of about 1.5.

As with Arctic amplification, this land-ocean contrast can be seen in observed warming. It can also be explained from basic scientific principles and is roughly analogous to the way a dry surface, such as pavement, warms more than a moist surface, such as soil, on a hot, sunny day.

The contrast has consequences for land-dwellers like ourselves, as every degree of global warming will be amplified over land.

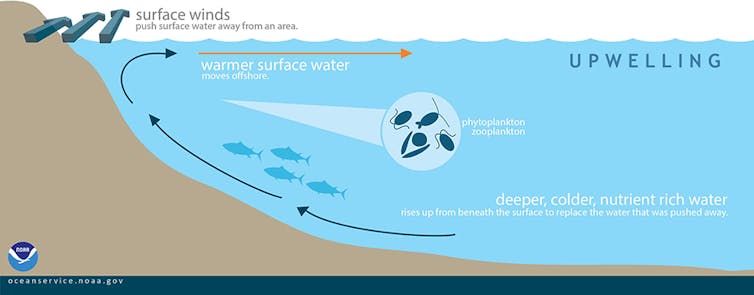

Forecast No. 5: Delayed Southern Ocean warming

Perhaps the biggest surprise from Manabe’s models came from a region most of us rarely think about: the Southern Ocean.

This vast, remote body of water encircles Antarctica and has strong eastward winds whipping across it unimpeded, due to the absence of land masses in the southern midlatitudes. These winds continually draw up deep ocean waters to the surface.

NOAA

Manabe and colleagues found that the Southern Ocean warmed very slowly when atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations increased because the surface waters were continually being replenished by these upwelling abyssal waters, which hadn’t yet warmed.

This delayed Southern Ocean warming is also visible in the temperature observations.

What does all this add up to?

Looking back on Manabe’s work more than half a century later, it’s clear that even early climate models captured the broad strokes of global warming.

Manabe’s models simulated these patterns decades before they were observed: Arctic Amplification was simulated in 1975 but only observed with confidence in 2009, while stratospheric cooling was simulated in 1967 but definitively observed only recently.

Climate models have their limitations, of course. For instance, they cannot predict regional climate change as well as people would like. But the fact that climate science, like any field, has significant unknowns should not blind us to what we do know.

![]()

Nadir Jeevanjee is a Research Physical Scientist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

Pogo says

@Uh-oh

https://www.google.com/search?q=challenger+uh+oh+recording

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Bip77l7zHng

Or, as Microsoft public relations, might say “… experts, thought leaders, and peers say…”; or Lex Elon Luther describes his modus operandi: the planet’s climate is possibly vulnerable to rapid disassembly.

Good night, and good luck.

Ray W. says

Earlier this year, BYD released what has been described as one of the most efficient hybrid cars currently available for purchase. The 5-seat, front-wheel drive Seal 05 DM-i is not an extended range EV, which uses an engine to drive a generator. The car’s engine, when running, drives the transmission, just as the car’s motor, when operating.

The Seal 05 DM-i, one of several Seal sedan models available for purchase, comes with a comparatively small Blade lithium-iron-phosphate (LFP) 15.84 kWh battery, with a battery-only range of 80 miles. When that electric-only mileage range is combined with the 99-horsepower 1.5-liter, four-cylinder engine’s mileage range, the total distance lengthens to 1,243 miles on a fully charged battery and a full tank of fuel.

Overall mpg derived from that fully-charged battery and fully-filled gas tank? 76 mpg.

Combined motor and engine horsepower is 260, with 248 lb-ft of torque. Time to accelerate to 100 kph (62 mph): 7.6 seconds.

The sedan is 188 inches in length, just over 72 inches wide, and almost 60 inches tall. Wheelbase is 107 inches. Weight as delivered: 4,310 pounds. These numbers are consistent with what qualifies as a mid-sized car in the United States. Not a compact car! Not a sub-compact car!

In October, BYD sold 15,661 DM-i models, among total sales of 71,248 Seal sedans of all available models sold that month. The DM-i model’s sales were up 23.8% from September.

Price in China at the dollar-yuan exchange rate: $11,240.

Make of this what you will.

Me?

The Chinese automotive manufacturing sector is in a state of winnowing. Of some 500 Chinese EV manufacturers active in 2019, perhaps 100 remained active four years on.

According to a Reuter’s article published this past July, by 2030 only 15 of those 100 remaining Chinese EV makers may still be in operation.

Who actually can predict that far ahead? Few, if any, among us saw the pandemic coming in December 2019!

A fierce price competition reminiscent of the disruption caused by the release of the Model T on the early American car industry is prompting the same disruption in today’s Chinese EV industry, weeding out the weak or the non-competitive.

BYD, by far the current sales leader, while profitable and well-positioned for the challenges inhering in the industry, is not immune to possible future failure. Warren Buffett, who bought into BYD in its infancy, divested from the company several years ago.

Nonetheless, with the 100% tariff that former President Biden imposed on all Chinese-made EVs in 2024, and not factoring in the ever-changing tariff rates imposed by President Trump thus far this year, $11,240 in China means the equivalent of a potential sales price in America of $22,240 for a well-equipped subcompact car.

Dollar for dollar, the best of today’s electric vehicles are better than the best of today’s gas-powered vehicles. Auto industry reporters repeatedly claim that Chinese cars match Western legacy vehicles in both fit and finish and standards for noise, vibration, and harshness (NVH).

EVs are now longer-lasting, less expensive to maintain and repair, and less expensive to drive, compared to gas-powered cars.

Given that insurance companies factor into premium quotes the replacement cost of totaled vehicles, EVs should be cheaper on average to insure, too.

Pogo says

@Hello Ray

Thank you for your generous exertions to inform about, and explain, the topics you comment on.

Interesting times indeed…

https://www.google.com/search?q=may+you+live+in+interesting+times

I fear inertia has already sealed our fate. I’ve had my day under the sun, God, help the young, the lost, the innocent — all who have no other hope. Nature is a hanging judge.

Ray W. says

Hello Pogo.

I, too, fear that the world has already passed a tipping point in the realm of climate science.

I can’t shake the idea that only about 1 billion people in the more developed world have easy access to climate controlled homes, personal transport, and electronic paraphernalia. If correct, that means that seven billion people do not have such easy access. How many of those seven billion want climate controlled homes, personal transport and electronic paraphernalia?

As I have repeated many times, should a young Thai or Bengali, or Uruguayan or Lebanese married couple both graduate with college degrees and then accept by arbitrary decree that they can’t have the things they want? Of course not! They will work hard to get those things, even if it means adding to the strain on our climate.

We are adding solar and wind power all over the world at incredible rates, but demand for electricity is rising even faster. China is adding solar and wind power at a rate much higher than we are. But China has four times our population and China is the world’s greater consumer of electricity. Yes, in 2024, 80% of China’s rising overall demand for electricity was met by solar and wind power additions to the grid, but that means that 20% of the rise in demand was met by other sources, mostly fossil fuels in nature.

One estimate has global sales for cars and light trucks at over 85 million units in 2024. EV sales are rising at a much faster rate than the rise in overall vehicle sales, but EVs are still only roughly 25% of the total.

According to the EIA, China saw a drop in demand for gasoline of over 14% from August 2023 to August 2024. China’s EV sales now constitute roughly 50% of all new cars and light trucks sold, but there exists a mass of used gas-powered cars that will take years to age out of the motor pool.

Sherry says

Oh Wait! Climate Change is one big “HOAX”, right? The Maga “Lord and Master” trump says so. . . therefore we should all disbelieve “ALL” scientific proof to the contrary! Right Maga? Right?