By Charlotte M. Canning

On Aug. 20, 2022, a large crowd gathered in front of the New York Public Library to hear prominent authors such as Kiran Desai, Gay Talese and Colum McCann read from novelist Salman Rushdie’s works. The event was organized as a demonstration of support for Rushdie after he was brutally attacked during a lecture on Aug. 12.

The Indian-born writer has been the subject of death threats ever since the publication of his 1998 book “The Satanic Verses,” which some Muslim leaders condemned as blasphemous.

The speakers at the Aug. 20 reading stressed free speech. But they may not have known that the very place where Rushdie was attacked, the Chautauqua Institution in western New York state, was founded nearly 150 years ago on similar ideals: the free exchange of ideas and learning to benefit individuals and society.

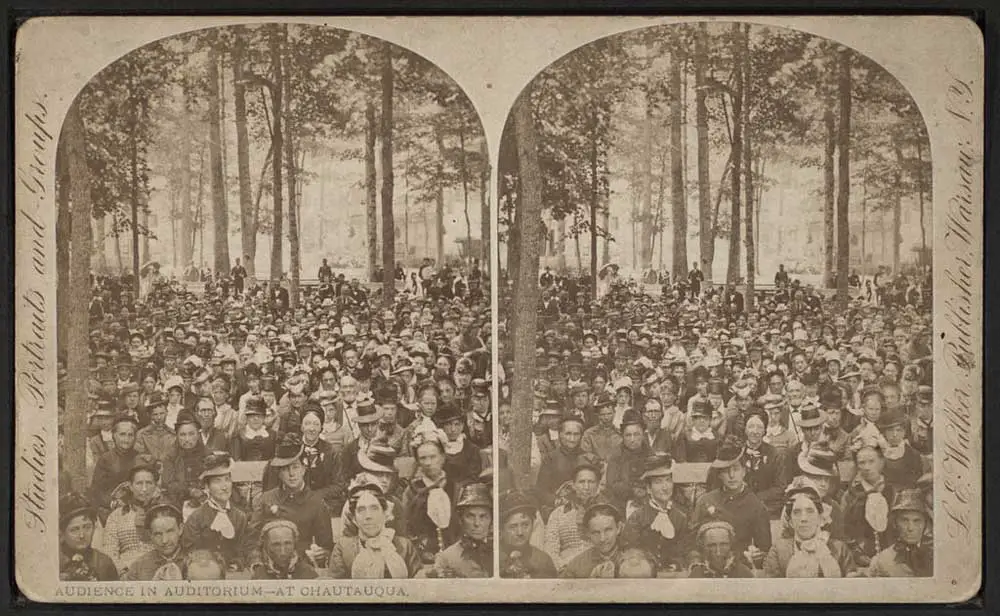

What began as a summer camp for Sunday school teachers grew into a national network of lectures, classes and performances. President Theodore Roosevelt supposedly called Chautauqua “the most American thing in America” – a phrase I borrowed for the title of my book about the lecture circuit. The institute aimed to “discuss questions and solve problems,” while “exalting education of all, everywhere, without exception,” as one founder declared.

Chautauqua has never been immune from larger national tensions and sometimes failed to live up to the inclusive vision it proclaimed. But its founding values are those that Rushdie’s supporters were seeking to defend.

AP Photo/Joshua Goodman

Learning by the lake

When the Chautauqua Institution held its first meeting in 1874, the nation was still bitterly divided in the wake of the Civil War that had ended less than 10 years before. Reconstruction was changing the South, and by extension the entire country. Meanwhile, an economic boom helped create an explosion of immigration and a widening gulf between the rich and the poor.

Into this volatile political, social and economic situation stepped Chautauqua. The institution’s two founders – John Heyl Vincent, a Methodist bishop, and Lewis Miller, a Midwestern businessman – created a summer educational program for Sunday school teachers in an outdoors setting. Their idea was inspired by the “camp meetings” popular in rural areas, especially in the South and West: religious revivals where Protestant Christians would preach outside. But Vincent and Miller wanted to replace exhortation and spectacle with study and research.

Chautauqua soon focused on education more generally, and its religious focus became increasingly interdenominational. Four years after its beginning, the institution established the Chautauqua Literary and Scientific Circle, which expanded the center’s focus on self-improvement into a guided reading series, and eventually became the first correspondence degree program in the U.S.

Chautauqua pioneered the adult education movement, with the idea that everyone deserved access to what is now called “life-long learning.”

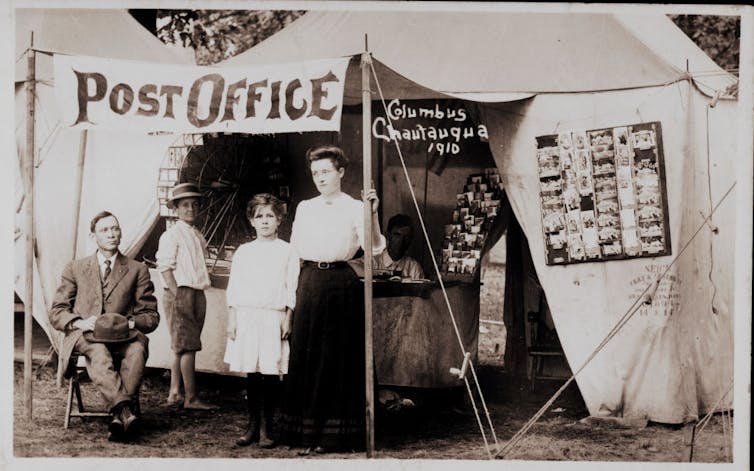

The “Chautauqua Ideal,” as its adherents called it, did not remain contained to a small enclave on the banks of a lake in New York state. Not long after the reading circle program began, communities around the country decided to establish their own Chautauqua assemblies. One of the few that remain today is in Boulder, Colorado. Like the original Chautauqua, people would come for weeks at a time to attend classes and enjoy social activities.

Vintage Images/Archive Photos via Getty Images

The expanding railway system, meanwhile, sparked a new possibility: Circuit Chautauqua. Commercial bureaus that managed performers’ and speakers’ schedules set up networks of seasonal Chautauquas and would rotate the talent through each circuit. From their start in 1904 up through their heyday in the 1920s, the circuits played to millions, and at their peak appeared in almost every state.

Democratic experiment

What drew people to every incarnation of Chautauqua around the turn of the century was the promise of transformation, self-improvement and a sense of uplift. Whether a person traveled to New York or experienced Chautauqua in their own backyard, they felt that knowledge and self-expression were theirs for the taking.

As a woman from Kansas, whom I quote in my book, enthused to a reporter in 1910, “the town never was the same after Chautauqua started coming. The Chautauqua brought a new touch of culture which we immediately applied to our lives: new ways of speech, dress, ways of entertainment. … It broadened our lives in many ways.”

Talk about democracy, access to knowledge and open discussion was everywhere in Chautauqua. The movement took off during the Progressive Era of about 1890 to 1920, a time of political and social reform in the United States. Activists agitated for democratic reforms, ethical government and the improvement of everyday life, such as food safety regulations.

Reformers called for improved public education, especially as a way to integrate new immigrants into civil society. Chautauqua became a key site for the exchange of ideas on how to achieve Progressives’ aspirations.

Despite being a platform for free and respectful speech and debate, however, Chautauqua has also reflected larger social divisions and prejudice. For decades the New York version remained, as historian Andrew C. Rieser described it, “lily-white to the core,” and the others were not much different. Chautauqua was not revolutionary and never led the charge on issues like suffrage or civil rights. People of color who appeared in Chautauqua had to endure much harsher conditions than their white counterparts, such as having to leave segregated “sundown towns” at dusk after they performed, and other oppressive experiences.

Free speech then – and now

As the nation struggled to become more inclusive, so too did Chautauqua. Today, its values of reading, critical thinking and open listening are as relevant as they were in the upheavals of the 19th century.

When Rushdie’s assailant rushed to the stage, the novelist was speaking in a lecture series called “More Than Shelter.” The day’s discussion was to have focused on “the United States as asylum for writers and other artists in exile and as a home for freedom of creative expression.”

Chautauqua was founded to discuss those kinds of ideas, although on that day it was no asylum. Yet its continued existence is a reminder that people can insist on thoughtful ideas to transform themselves and their communities for the better.

![]()

Charlotte M. Canning is Frank C. Erwin, Jr. Centennial Professor in Drama at the University of Texas at Austin.

Leave a Reply