Circuit Judge Terence Perkins has ruled against a motion to exclude from trial a key interview between two detectives and Larry A. Cavallaro at his home in Flagler Beach in 2018, where the detectives were investigating an allegation that Cavallaro had raped a woman.

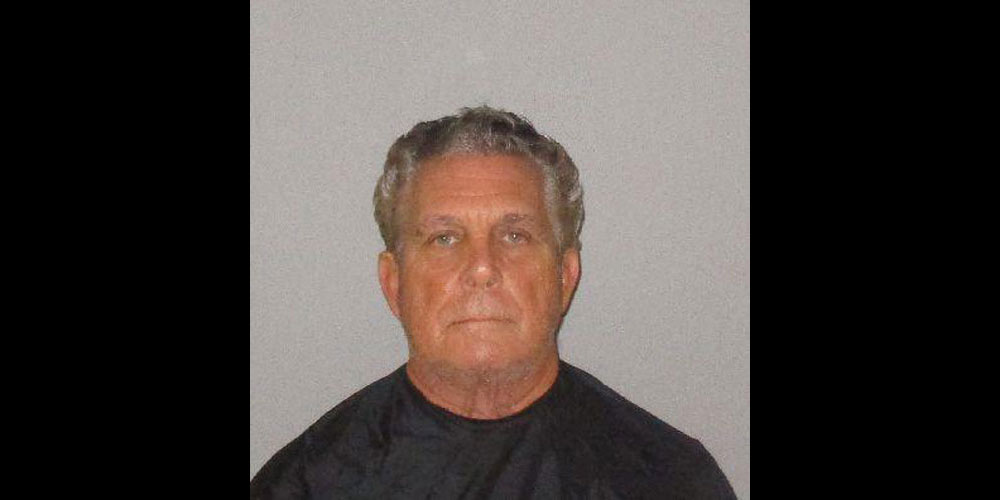

Cavallaro, a former gallery owner in Flagler Beach who divided his time between Winter Park and the beach town, was arrested on June 12, 2019, on a first-degree felony rape charge stemming from an allegation that he drugged and raped 40-year-old woman who had gone to visit him there with a friend. He’s been free on $100,000 bond. He’s pleaded not guilty.

The woman had known Cavallaro for about a year and a half. He was employing her to help him rent out his beach house in Flagler Beach. He’d invited her and her friend over to pay her for that assistance.

The incident allegedly took place on December 17, 2017. The interview took place on Jan. 25, 2018, when detectives Nicole Quintieri and Robert Blanton (Blanton has since left the agency) went to Cavallaro’s home at 2654 North Oceanshore Boulevard to speak with him about the encounter. “Do you mind if we come in and talk to you for a couple of minutes?” they’d asked him.

“Sure, any time,” Cavallaro replied, inviting them in. They then sat at his dining room table and chatted.

According to the detectives’ report, Cavallaro during the interview admitted to “making out and rolling around in the bed,” but that the woman was “out of it” and he was not interested in having sex with someone in that condition. After Cavallaro claimed she took her friend back to her car, she returned and herself made moves on him. (In her friend’s account, it was Cavallaro who took her back to her car, not the woman.) He then conceded that there’d been oral sex, but with little additional information. In Perkins’s words, Cavallaro’s “description of events contained numerous statements that could be considered as admissions.” (Perkins had listened to the tapes.)

The interview was recorded without Cavallaro’s knowledge or consent, as had been a “controlled” phone call a week earlier between Cavallaro and the victim, with detectives listening. But in the phone call, which ended abruptly when the victim got upset, Cavallaro did not admit to sexual acts. He did not deny them, when the victim spoke of them. But there’s no such thing as an admission by inference in a court of law. In the subsequent interview with detectives, however, he does admit it, making that recording essential to the prosecution’s case–and just as essential for the defense to exclude.

Cavallaro’s attorney, Warren Lindsey, argued before Perkins in a motion and a pair of hearings earlier this month that the interviews with detectives were not voluntary, and therefore should be suppressed. Cavallaro, he said, felt compelled to speak with law enforcement because they showed up at his door and he didn’t feel he had a choice. Cavallaro isn’t contesting the detectives’ right to record individuals secretly (it’s part of police’s routine investigative techniques, but he felt the interview was not consensual and that the admissions were not provided voluntarily.)

The interview was never confrontational. Assistant State Prosecutor Melissa Clark contends that nothing about it was involuntary.

“Yes, then everything about the conversation was very free flowing, we would ask questions we would make statements he would provide responses. It was all very, very easy communication,” Quintieri testified at one of the two hearings. “He was very talkative. There were points where he might have been a little bit nervous. He made the statement several times during the interview that he wasn’t this kind of person, that we could check the record to those kinds of things but as far as his demeanor, very talkative, very cooperative.”

At the end of the 45-minute interview, “we thanked Mr Cavallaro for allowing us into his home, and then we left.”

Lindsay characterized the detectives’ techniques as “lies” told to Cavallaro to “get him to make statements to answer your questions.”

“It was used as an investigative technique,” Quintieri said.

“The lies were intended to get him to make statements, to make statements to the response to the lies that were told.”

“Yeah,” the detective replied.

Lindsay was attempting to get at some form of entrapment showing that the exchange had not been voluntary, using words like “lies” to convey the supposed inappropriateness or aggression of the detectives. But courts have ruled such techniques as legal, too, so Lindsay was merely circling around the detective, trying by various means to elicit an answer he did not get, other than objections from the prosecution that he kept asking the same questions. When Lindsay asked Blanton if the detectives’ statements could have coerced Cavallaro into answering, Blanton said: ‘That’s not the way it came across.”

Cavallaro, who attended the hearings by Zoom (as did all involved, with Perkins in his courtroom), characterized the detectives’ visit as conducting a “survey,” then thought it was an “official investigation,” compelling him to speak with them. He said they never told him that he had a choice–that he didn’t have to talk to them, though since then-Chief Justice William Rehnquist described in a 2000 decision how the Miranda warning against self-incrimination “has become embedded in routine police practice to the point where the warnings have become part of our national culture,” rare are those who do not know that they do not have to talk to police if they don’t wish to. Lindsay’s contention was that the detectives never read him his Miranda warning. The prosecution’s contention is that it was a consensual conversation from the start. The murkiness is often contentious, leading to such motions to suppress.

“So, the issue for the Court is whether the defendant’s statements or admissions were voluntary and, therefore, admissible,” the order reads.

“To establish that a statement is involuntary, there must be a finding of coercive police conduct,” the ruling continues. “This determination must be based upon how a reasonable person would feel under similar circumstances, that is, whether a reasonable person would feel compelled to give a statement to law enforcement under similar circumstances. The defendant’s subjective beliefs are not relevant.” Perkins described Cavallaro as a “mature and successful businessman with many years of experience selling real estate on a national level,” a diplomatic way of saying that Cavallaro has been around the block and is no sap.

“He was not impaired or distracted and didn’t appear intimidated or guarded when conversing with the 2 detectives,” the order found. “Not once did [Cavallaro] indicate that he did not understand why he was being questioned. Not once did [Cavallaro] indicate that he was uncomfortable or hesitant about talking with the detectives. [Cavallaro] had a clear recollection of the incident and voluntarily disclosed the events of the evening with little prompting from the detectives. The interview could accurately be described as a polite, cooperative conversation.”

“More importantly,” regarding the detectives’ conduct, “there is absolutely no evidence from which to conclude that the conduct of the detectives was so coercive and threatening that such conduct deprived the defendant of his free will deciding to talk with police.” Perkins denied the motion verbally on March 19, but formalized it in an order (see below) last week.

The decision is not a judgment about the validity or the substance of Cavallaro’s interview, including its alleged admissions. It only means that the jury will get to hear parts or all of the of the recorded interview, if the prosecution chooses to play it, as often happens in such cases. It’ll be up to the jury to weigh the meaning of the statements. The case now continues to make its way to trial, with additional depositions continuing.

A previous order granting the prosecution authority to take a DNA sample from Cavallaro points at the sort of evidence in its possession, since that sample was taken for comparative purposes. It also anticipates the sort of arguments the two sides will present if and when the case gets to trial, the issue coming down to an echo of that interview with the detectives: was the sex consensual or not, with the evidence and degree of impairment playing a key role in the determination.

Based on details disclosed by the prosecution filed, the alleged victim will testify that she’d gone to Cavallaro’s house after work the afternoon of Dec. 17, with her friend, he’d poured them what he called a “rum runner” he’d prepared before they showed up, and after sipping just that one drink as the trio sat on the patio facing the ocean, she began feeling intoxicated to the point of having trouble making her way to the bathroom. She will testify that it was her last memory before she woke up naked in Cavallaro’s bed.

A toxicology report revealed that she had several substances in her system, and was ill the next day. Her friend will also testify to much the same effects after drinking only some of the rum runner, including falling unresponsive when she got home later that afternoon and becoming ill during the night. The prosecution will seek to link the two women’s response to the drink. “It is the state’s position that had [the alleged victim’s friend] not left the residence,” the state contends in a motion, “she too would have become a victim of sexual battery at the hands of Larry Cavallaro.”

The defense for its part is contesting the toxicology report’s accuracy and is seeking to suppress it, in effect underscoring the prosecutorial weight of that evidence. The defense argues that a report by one lab of the alleged victim’s fluids conflicted with findings in a Florida Department of Law Enforcement Analysis. The defense is also objecting to the prosecution’s motion to connect the effects of the drink to both women. The court has not yet ruled on those motions.

![]()

Yellowstone says

Anybody here know Larry’s business background? His name and face are familiar.