When the city of Bunnel canceled all special events through 2015 for financial reasons, including what used to be the annual Bunnell Potato Festival, Mari Molina and a few others were not pleased. It’s bad enough that when it comes to special events, or even to its place on the map, Bunnell tends to be marginalized in the shadowy sprawls of upstart Palm Coast, a town younger than most of Bunnell’s manhole covers.

Now Bunnell was marginalizing itself by cancelling the one big event designed to counter that perception. “That should never have happened,” long-time Bunnell resident and business owner Thea Mathen says.

It was part of Bunnell’s austerity program, implemented last year in the face of a gaping budget deficit. The response to the cancellation of the Potato Festival from the community was more like a shrug, according to City Manager Larry Williams. “No backlash at all. A couple of people said we should still have it,” he says. “I think that when it was explained, ‘Do you cut people or do you cut events?’ It’s very easy to understand which one you do.” (The city cut people, too: its police department lost a third of its manpower.) The city had approached the Chamber of Commerce which played an integral part in coordinating the Potato Festival. All agreed: “We’d put all our effort into putting on a much better event in 2016,” Williams says.

Molina wasn’t going to wait. She is president of Bunnell-based Flagler Cats, the non-profit. She’s also on a Bunnell cheerleading squad that’s always included her, Thea Mathen, Mark Langello and a few others, some of whom don’t even make their home in Bunnell but, like Tony Bennett speaking of another town, leave their heart there no matter where they are. The city government was going to do what it had to do. But Molina saw an opportunity. If the Potato Festival had been about the potato, she would make of it her own little Lazarus and sprout it into a lot more than an homage to potatoes. She would put the spotlight on all the county’s agriculture industries which helped fuel Flagler County’s growth. Industries like turpentine, for example, cattle, cabbage, and timber, all played a role.

“Before everything was potato, potato, potato,” Molina says, as if creating her own B.C. and A.D. eras. That era is here. The Bunnell Festival gets its debut Saturday morning, starting at 10, and running until late afternoon on the same grounds in front of the old city hall, near the old courthouse. There’ll be potatoes, to be sure–those freshly made french fries–but there’ll also be live music, a dog show, children’s games, and vendors all over the place. It’ll be the potato festival with wings.

Molina hopes the Bunnell Festival will be more community–focused than was the Potato Festival. She reached out to numerous local agricultural organizations to emphasize that approach, including Bunnell Elementary, which has its own flagship agricultural program and to 4-H, the youth leadership program operated by the University of Florida’s extension. “It’s not about only potatoes, it’s about everything that goes on in Bunnell.”

Or even did.

Because Bunnell has one thing Palm Coast doesn’t: history.

Bunnell’s place on the map is too often overshadowed by the bedroom community next door.

Palm Coast doesn’t even have the sort of people who were born and raised in the town they still call home, who went to the same elementary school, necked under trees that still shade Bunnell memories.

Some of the town’s memories are nothing to be proud of, of course. If trees could talk, and some of their branches more than others. It was an authentic Southern town, so it’s no mystery that blacks were often treated as subhuman creatures. Even their dead were exiled from town: the Masonic Cemetery on Old Kings Road is a testament to that brutal era, when a developer could trample the town’s only black cemetery to build new homes and force blacks to bury their dead five miles away, while another town–Flagler Beach–did Bunnell one better by simply banning blacks, alive or dead, especially after sundown. That’s why you’re not likely to see an overwhelming number of black residents wander into the festival, even though it’s taking place on the rim of their neighborhood: some memories are less celebrated than others. But that’s another story.

And in Bunnell as elsewhere, it’s taken the progressive work of certain people to detach the town from its less distinguished past.

Thea Mathen was born and raised here. Her business, Dave’s A1 Auto, also an event sponsor, has been in the same location since 1959 (though it didn’t always have the same name). It’s located in Favoretta, an unincorporated community that originated as a turpentine stop on a rail line. The county population numbered about 5,000, pre-1967, when Mathen was growing up. She graduated from Bunnell High School; her class was comprised of 67 students.

Mathen parlayed agriculture part of Leadership Flagler, a chamber program focused on making future community leaders literate in various aspects of Flagler County. Everyone she knew, growing up, and everyone she went to school with, was involved in some way with agriculture. That’s why she landed that position. But these days few people she interacts with in the Chamber of Commerce program are agriculture-literate. “They’re clueless,” Mathen says. They think the county’s made up of just Palm Coast and the beaches, as if the $303 million estimated impact of agriculture on the local economy were as as ephemeral as morning fog on potato fields.

She’d take them “to get up close and personal with cow,” Mathen says. “We’d have farmers speak to the trials and tribulations of growing cabbage and potatoes.” She took them to Hollar and Green, the big packaging and distributor plant of cabbage in western Flagler so they could witness how cabbage is processed, how they keep it cold, box it and transport it. “Most people think there’s nothing past U.S.1. But they get out there and they see these sod fields, cabbage fields, potato fields, vegetable fields,” Mathen says. There’s even broccoli fields now. “I don’t think people really realize that.”

If you were to take a tour, here are some sights you’ll likely encounter: where it pops up, some of what’s left of the one-lane, brick Dixie highway: most of it has been paved over. A brief history on some of the worn, storefronts that, if still in operation, bare a completely different look than when Sisco and Gloria were growing up in Bunnell, and also what remains of some of those old hotels like, the Halcyon, where George W. or his peers Issac I Moody and Frank Lambert would use to court potential land buyers through the Bunnell Development Company. There’re the old homes, particularly the one belonging to Gloria’s grandmother in Bull Creek, the second oldest house in the county. There’s the Azalea-strewn Espanola Cemetery, Flagler County’s oldest. To be buried there, you have to have family there. Both Deens do. You’ll get a full picture of the area that includes a quick detour through the Daytona North Mondex area, an area that sometimes makes the news.

And if you are to take a tour, Sisco and Gloria Deen are your best guides.

“If you haven’t been to the west side of our county—you really need to,” Gloria Deen says, as the car heads in the direction of tannin-colored waters of Lake Disston, named for Hamilton Disston, the early real estate developer who purchased four million acres of Florida land in 1881 and is known as “the man who saved Florida,” according to Sisco Deen, Gloria’s husband.

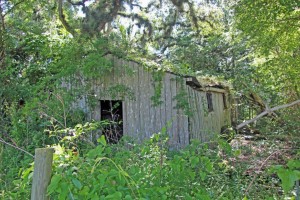

These days, the Deen family has stopped making history. Sisco merely soaks in it. He is the curator for the Flagler County Historical Society, though he knows the smell of turpentine the way younger people know the smell of video arcades. Reaching the Orange Hammock on a recent tour, he brings the car to a halt. His wife is in the passenger seat. There’s an abandoned shack of sorts by the overgrown roadside. It used to be a lot more than that. It was a turpentine commissary. There’s little chance that an uninformed traveler would drive by that turpentine still and give it a second glance, if the traveler notices at all. It’s just an old beat-up shed. But Sisco Deen is no uninformed traveler. He’s

Turpentine used to be huge in Flagler County: consider how much land is covered with pine trees, the resin used primarily for ship building. This particular still was set up by Sisco’s grandfather, James Emmett Deen, a long time ago, when turpentine used to be one of the county’s principal industries, sweating out pine trees’ resin for the solvent that was then used in shipbuilding. The industry began to die out during the 50s. It’s now extremely rare in Florida and non-existent in Flagler. That’s no reason to get sentimental over it, least of all in Deen’s presence. Is the commissary considered historic? “Nope,” he says with a shrug. “It’s just a place that used to be an old turpentine still.”

![]()

The Bunnell Festival, a celebration of the county’s agricultural history, is an all-day event to be held behind Bunnell’s old courthouse, Saturday, May 16, from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. In addition to all the on-scene vendors, events include roaming magicians, floating wonder balloons, a petting zoo, a bounce house and face painters, live music from the Country Blues band, Slickwood, and a dog show. Visit the Bunnell Festival website.

Leave a Reply