By Rachel Gordan

Eighty years ago, in the winter and spring of 1944, Brooklyn-born author Betty Smith was entering a new chapter of life.

A year earlier, she was an unknown writer, negotiating with her publisher about manuscript edits and the date of publication for her first book, “A Tree Grows in Brooklyn,” a semi-autobiographical novel about the poor but spirited Nolan family.

Now she was one of the lucky few. Her book was spotted in cafes, on buses and in bookstores all over town. The following year, when it was being made into a film directed by Elia Kazan, Life magazine reported, “Betty Smith’s ‘A Tree Grows in Brooklyn’ (2,500,000 copies sold) has become one of the best-loved novels of our time.”

New York in the 1940s was not the city we know today. The Empire State Building had not reached its full height, nor had the statue of “Alice in Wonderland” taken up residence in Central Park. And it would be decades before anyone was humming along to a tune that brashly commanded, “Start spreadin’ the news, I’m leavin’ today, I want to be a part of it: New York, New York!”

Brooklyn, too, was still becoming itself – and no other 20th-century American novel did quite so much for the borough’s reputation.

Readers fall for Brooklyn

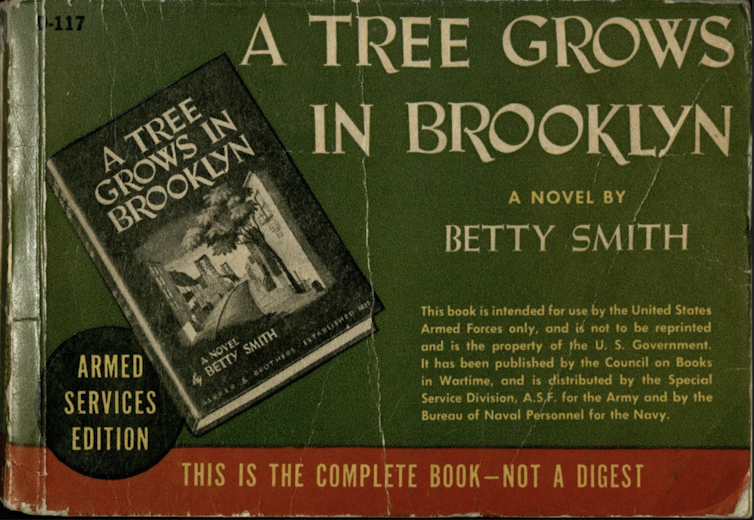

During World War II, writes law professor Molly Guptill Manning, “A Tree Grows in Brooklyn” was one of the most popular books among the Armed Services Editions, which were mass-produced paperbacks selected by a panel of literary experts for distribution to the U.S. military during World War II.

UNC Libraries

It seemed like everyone wanted to declare some affiliation with the novel-turned-film and, by extension, with Brooklyn. Even readers who had never set foot in the borough nonetheless found themselves enchanted by it through Smith’s portrayal.

As one reader wrote to Smith, “Raised as a ‘rebel of the old South,’ Brooklyn has long been my symbol of all yankee, thus learning to hate it; but now I have learned to love it through Francie’s eyes … as Francie loved it.”

Advertisers also took note, riffing on Smith’s title with tags such as, “A Dress Grows on Peggy,” or Rheingold extra dry lager – the “beer that grows in Brooklyn.”

Poverty loses its sheen of shame

Meanwhile, readers who had grown up in the borough responded enthusiastically to Smith’s evocations of their favorite neighborhood haunts, writing to her to share their own memories of the shops and streets that she had included in the novel.

“A Tree Grows in Brooklyn” had done something remarkable for them: It removed the veil of shame that surrounded tenement living and, as historian Judith E. Smith has written, helped them reclaim their humble origins.

And not just reclaim them. The novel affirmed the desire to move beyond poverty, as the protagonist, Francie, had done, and Betty Smith, too.

Francie’s wanderings through Brooklyn lead to her discovery of a more inviting public school than her own. With her father’s help, she manages to enroll in the school, which is better funded but farther from home. Despite the extra-long schlep, Francie sees it as “a good thing” to have found this new school: “It showed her that there were other worlds beside the world she had been born into and that these other worlds were not unattainable.”

It was a feeling that people of many backgrounds could understand, and not just in Brooklyn.

Compass Real Estate

Smith certainly understood the importance of broadening her horizons: Although she never finished high school, when her marriage to a University of Michigan graduate student brought her to Ann Arbor, she was able to audit classes as a special student.

There, her work for her playwriting classes led to a prestigious playwriting prize, and then an invitation to study at Yale School of Drama. Divorced at that point, Smith was free to pursue her education in theater at Yale. The theme of self-improvement through education made “A Tree Grows” relatable for readers of modest origins.

Readers were quick to see the novel as a paean to Brooklyn, and often sought to bond with Smith over their presumed shared love of Brooklyn.

“I hope you will give us further stories of the Brooklyn which you know, and, I am sure, love so well,” wrote one reader.

“Some day, if you have time, it might be fun to chew the fat a bit about old Williamsburgh (sic),” journalist Meyer Berger wrote to Smith after reading and reviewing her novel.

“Betty Smith obviously loves Brooklyn and is proud of it,” Orville Prescott declared in his glowing New York Times review.

Smith scorns the borough’s new arrivals

But did Betty Smith love Brooklyn?

After all, she wrote the novel while living in Chapel Hill, North Carolina – years after having moved away from New York.

Like so many who leave Brooklyn today, Smith did not return to take up residence, in part because she could not afford to live there on her own. By the time she had earned a windfall from “A Tree Grows in Brooklyn,” she had come to love Chapel Hill.

Smith also left Brooklyn with mixed feelings about her hometown. She wrote to her publishers in 1942, “If Hitler’s bombers should ever get over and if any portion of this great city has to be wiped out, it would be a blessing if it were (Williamsburg).”

“Evil seems to be part of the very materials that the sidewalks are made out of and the wood and the brick of the houses,” she added.

Although writing about Brooklyn had brought her fortune and fame, she had no desire to return.

As she explained in her 1942 letter, Smith perceived Brooklyn’s current situation as the result of a changing population and growing crime: “A hundred years ago, it was a quiet peaceful village settled by hard-working, sturdy, honest burghers,” Smith reflected in her letter, adding that even 25 years ago, Williamsburg was a gentler place. “But now it’s a fearful one.”

Smith offered her own analysis of the situation: “The feuds in the neighborhood came about because most of the Italians originally came from Sicily and were fierce and murderous. The Jews in the neighborhood were mostly Russian Jews, conditioned to pogroms and much fiercer and more ready to fight.”

Weegee/International Center of Photography via Getty Images

Like many Americans at the time, Smith held some entrenched and intolerant views about immigrants and their character. Since she was often invited to contribute guest essays to publications during the height of her fame, she had ample opportunity to express her worldview.

After World War II, Smith directed this hostility toward foreigners at America’s wartime enemies. In her August 1945 essay “Thoughts for These Days of Victory,” she encouraged readers not to forget their anger at wartime enemies: “Let us hold this bitterness so that we’ll not again be lulled into a false sense of security. The war proved conclusively that not all men are brothers and that not all nations are sisters.”

A full understanding of the Betty Smith behind the novel that changed how Americans felt about Brooklyn – and their humble origins – are complicated by Smith’s own views and her experiences away from Brooklyn.

As Smith knew, making something of yourself often requires leaving home. It’s hard to tell whether distance made her heart grow fonder. In leaving Brooklyn, Smith had not suddenly started seeing her hometown through rose-colored glasses.

In Chapel Hill she was finally able to see Brooklyn – and write about it – in a way that brought readers of all kinds closer to Brooklyn and legitimized their own origin stories. That, in and of itself, is a kind of love, even if it’s not the unconditional kind so many had imagined.

![]()

Rachel Gordan is Assistant Professor of Religion and Jewish Studies at the University of Florida.

Pogo says

@Deserves a soundtrack…