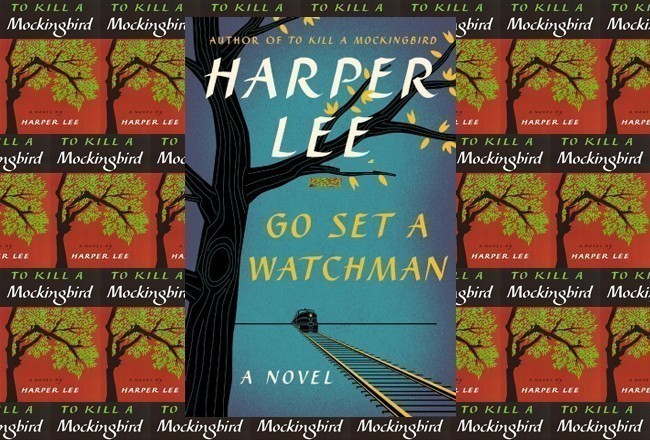

Welcome to part eight of FlaglerLive’s live-blogging of “Go Set a Watchman.” We’ve invited 10 people of varied backgrounds from around the community to read the book and write their response to each of its 19 chapters, from whatever perspective they choose, at whatever length they choose, in 19 installments over the next few weeks. For a few more details on the project, read the introduction here. As always, we start with a summary of the chapter at hand and dive into the critics’ responses. So you’re forewarned: the spoiler alert is implied.

![]()

Our Ten Critics: Quick Links

- Today’s Chapter Summary

- Jon Hardison

- Monica Campana

- Mark Carpanini

- Inna Hardison

- Jay Livingston

- Bill McGuire

- Brian McMillan

- Mary Ann Clark

- Pierre Tristam

![]()

Chapter 8 summary: The first paragraph warns that the fun is over. This is where Jean Louise is “yanked from her quiet realm.” It’s Sunday afternoon. Her father goes to a meeting at the courthouse. He doesn’t say what it’s about. But Jean Louise soon finds out: as she’s picking up the living room, she finds a pamphlet her father had been reading: “The Black Plague.” No, not the black death of 13th century Europe, but “stuff in that thing” about blacks in the South that “makes Dr. Goebbels look like a naive little country boy[,]” in Jean Louise’s disbelieving words to her aunt Alexandra, who believes in the pamphlet. Her father has gone to the Maycomb County Citizens’ Council, a KKK-like organization that meets at the courthouse. Jean Louise, incensed, goes there and climbs to her old spot in the courthouse balcony, where she’d once watched her father defend Tom Robins. Now she sees him below as once with the racists. More: as their leader. And she sees her own Henry, part of the bigoted crowd: “The one human being she had ever fully and wholeheartedly trusted had failed her; the only man she had ever known to whom she could point and say with expert knowledge, ‘He is a gentleman, in his heart he is a gentleman,’ had betrayed her, publicly, grossly, and shamelessly.”

Jon Hardison, co-owner of Ha Media in Palm Coast and member of the FlaglerLive board of directors: It begins…

Jon Hardison, co-owner of Ha Media in Palm Coast and member of the FlaglerLive board of directors: It begins…

The last paragraph of Chapter 8 reads, “The one human being she had ever fully and wholeheartedly trusted had failed her; the only man she had ever known to whom she could point and say with expert knowledge, ‘He is a gentleman, in his heart he is a gentleman,’ had betrayed her, publicly, grossly, and shamelessly.” In defense of segregation, Atticus and Henry both found themselves, with nearly all other men in Maycomb, willful members of the “Maycomb County Citizens’ Council.” Atticus was on the board of directors. Jean Louise’s tip came in the form of a brochure she stumbled on containing all the language of supremacy one might expect. Given the time, history and geography no one, including Scout, could be the least bit surprised at the appearance of the council, disturbing as it is to look back on now. But Atticus at the helm of such a thing is simply too much for Scout and, I’d hope, most readers.

She walks the empty streets of the city straight for the courthouse, all the while trying to convince herself that there must be a reason Atticus and Hank are there. They must be keeping an eye on things. Up the stairs she goes and into the negroes’ balcony. All of Maycomb’s men, notable and not, are in attendance as Atticus rises to introduce the speaker du jour. A man named Grady O’Hanlon, who, after one opening joke, made the motions required of a man that needs to convince a crowd of something they’ve already given into – the rolling up of sleeves, unbuttoning of collars and loosening of ties (like a snake shedding its skin) that, to this day, are the hallmarks of morons pining for positions of leadership. They say things like, “Relax. I’m with you.”, and “Yeah buddy. I hear you.”

Like a snake that’s eaten something far too big to swallow, Mr. O’Hanlon stands and begins to puke. Here’s how I like to image it…

He opens his mouth, sweat pouring down his face, “NIGGAAAAGLE-GLURF-AAAAAHHH!!!” He can’t get it out. It’s too big, but his innards persist and the bile behind the whole swine he’s trying to pass finds weakness in his jowls, spraying a warning that those in attendance should vacate or at the very least move back. “JEWS AAAAAAAHHH!” He somehow finds a way to take some air… “JEWWWAHH-GLAWPURRRRREEEEE!!!” and with a thud it’s finally out.

Sadly, Scout wasn’t granted my version of events and had to sit through the reality of a meeting her father, for all intents and purposes, had called and organized himself. Sick to her stomach (as a bystander of either telling would be) she leaves the courthouse.

This time the hollow streets of Maycomb smell her contempt – they know she doesn’t belong and now Scout knows it too.

Monica Campana, just-retired head librarian at Indian Trails Middle School and free-speech advocate: “Betrayal is the only truth that sticks.” – Arthur Miller

Monica Campana, just-retired head librarian at Indian Trails Middle School and free-speech advocate: “Betrayal is the only truth that sticks.” – Arthur Miller

Poor Jean Louise is betrayed in Chapter 8. I will return to my first statement in Chapter 1: this young woman annoys me. No one wakes up at the age of 25 and discovers their father or town is racist. It is there and it has always been there for all of us who grew up in this country.

It was there in the story my mother told me about her first job in Camden, N.J. She barely spoke English and was lucky to find work in a factory sewing up the back seams in stockings. She befriended a young woman and invited her and her husband over for Sunday dinner in Gloucester City, N.J. When the young black couple exited their car the landlord came running out of the house waving her arms in the air and shouting, “No! They can’t come in here!” My mother stood in shock and embarrassment as the couple drove away. You would be hard pressed to find a black family living in Gloucester even today.

It was there when a young black family shopping for homes in south Jersey made the mistake of looking for one in our lily white neighborhood during the 60s. Housewives stood on their doorsteps in their aprons and stared as if to say, “Not here.” You would be hard pressed to find a black family living in West Deptford even today.

It was there when my friend parked her car in front of my house in Wilmington, N.C., and we drove together to judge a cheerleading tryout. When we returned and were talking next to her car, neighbors slowly began appearing on porches to stare at us. I told her, “Carolyn, we’re going to freak these people out—give me a big hug before you go.” We hugged and she drove away laughing. You would be hard pressed to find a black family living in Sunset Park to this day. The original 1925 deed on the property we purchased there clearly stated, “No sale to Negro.” We could not believe the unspoken in New Jersey was there in black and white in North Carolina.

It was there when my adopted black son attended my birth son’s play with me in the 80’s at Lockhart Elementary in Orlando. White women should never be seen with teenaged black boys. You would be hard pressed to find a black family living there today. Why would they want to—it is known as the local hangout for KKK members. Once on our way to school we saw a house with those letters painted on it.

In the 90’s I drove a suspended offensive lineman named John to Avon Park for a football game and when we stopped at a convenience store north of the Everglades the worker made a comment under his breath about white women dating black men. My three little children were with us and I was in my 30s. John leaned over to me (he was 6’2’’ and 300 lbs. at 17) and whispered that we should hurry up and get out of there.

It was there a few weeks ago when Oklahomans greeted our president by lining the streets and waving confederate flags at his passing car. Ironically, Oklahoma wasn’t even a state during the Civil War. What heritage were they proclaiming?

I am an old white woman with blonde hair and blue eyes and I have seen it, known it and fought it all my life. I cannot begin to imagine what it’s like to actually live it. My heart aches for every black parent who hugs their child before they head out the door each day. I cannot imagine what you say to your child to keep him or her safe. But no child of the South, black or white, has ever had a revelation like Jean Louise’s so late in life. Scout of Mockingbird knew it at age 8. Atticus and her town did not suddenly join these organizations or come to a way of thinking when she was a grown woman. It was there all along and she would have known it. She would have spent her teenage years arguing with her father over breakfast about it. She would have been on that Freedom Rider bus instead of reading about in the New York papers. She would have referred to Emmett Till’s death by name instead of mentioning it in passing as, “that Mississippi business.”

The writing didn’t bother me this go round. The content did.

Circuit Judge Mark Carpanini took office in the Tenth Judicial Circuit in Florida in 2005 in Polk County, where he still serves: The entire book until now is a prelude to Chapter 8. It starts with Jean Louise discovering at home a pamphlet from what is euphemistically called a “citizens’ council.” The pamphlet depicts a “negro” on the cover with the caption, “The Black Plague.” Jean Louise has some passing familiarity with these, having read about them in the “New York papers.” She peruses the article and learns that it expounds the biological inferiority of blacks. She is further surprised to learn that Atticus is on the board of directors of the citizens council and at that instant attending a meeting. She goes to town and slips into the courthouse where the meeting is being held and slips into the “colored” balcony to, in effect, spy on the meeting. What she hears confirms her suspicions in the worst possible way. The speaker delivers a speech full of all manner of racial invective complete with the words Jean Louise theretofore thought was reserved unto the “trash” element of southern society. But no, the room was filled with all of the “Men of substance and character, responsible men, good men.” And worst of all, Atticus and Hank, whose very presence meant they condoned the proceedings. The same Atticus who earlier had, risking great personal harm to his reputation, gotten an acquittal for a black man accused of raping a white girl. You might as well have punched her in the face full might with a closed fist.

Circuit Judge Mark Carpanini took office in the Tenth Judicial Circuit in Florida in 2005 in Polk County, where he still serves: The entire book until now is a prelude to Chapter 8. It starts with Jean Louise discovering at home a pamphlet from what is euphemistically called a “citizens’ council.” The pamphlet depicts a “negro” on the cover with the caption, “The Black Plague.” Jean Louise has some passing familiarity with these, having read about them in the “New York papers.” She peruses the article and learns that it expounds the biological inferiority of blacks. She is further surprised to learn that Atticus is on the board of directors of the citizens council and at that instant attending a meeting. She goes to town and slips into the courthouse where the meeting is being held and slips into the “colored” balcony to, in effect, spy on the meeting. What she hears confirms her suspicions in the worst possible way. The speaker delivers a speech full of all manner of racial invective complete with the words Jean Louise theretofore thought was reserved unto the “trash” element of southern society. But no, the room was filled with all of the “Men of substance and character, responsible men, good men.” And worst of all, Atticus and Hank, whose very presence meant they condoned the proceedings. The same Atticus who earlier had, risking great personal harm to his reputation, gotten an acquittal for a black man accused of raping a white girl. You might as well have punched her in the face full might with a closed fist.

As an aside, an interesting divergence with the movie and the book here is the defendant’s acquittal, whereas in the movie and the book he is convicted. And of interest to lawyers is the revelation that the indictment was poorly drafted so as to not charge Tom Robins with the crime of statutory rape, to which consent is not a defense but was the central feature of the case Atticus presented.

Jay Livingston, attorney with Livingston & Sword in Palm Coast: This chapter is much too important to go into much detail. While I might have recounted some of the events described in the preceding chapters I do not think I have given anything up that spoiled the story. I think this chapter is too critical to the joy of reading the book to give away too much so I will be brief even if it deserves more commentary than any other chapter so far.

Jay Livingston, attorney with Livingston & Sword in Palm Coast: This chapter is much too important to go into much detail. While I might have recounted some of the events described in the preceding chapters I do not think I have given anything up that spoiled the story. I think this chapter is too critical to the joy of reading the book to give away too much so I will be brief even if it deserves more commentary than any other chapter so far.

Racism is alive and well in the South. That is not a surprise today and definitely not in the time of our story. But who are the racists? Not those that spew vitriol about the other races, who wear their convictions on their sleeves and leave no doubt. Like public-access white supremacists that used to be on T.V. after midnight back in the 90s. We are definitely introduced to one of those. What about the unexpected segregationists? Is he hateful and ignorant or is it because of fear? As Hank’s and Uncle Jack’s comments already suggest, does the forced change of a culture, the dominance of the republic over democracy, convert even the apparently enlightened when it feels their entire way of life, not just the bad parts, is under attack. Or do the wise revert back to reactionary kooks in old age? All I know is our hero may be an anti-hero and it is disheartening.

The book just went from being interesting to good in a few pages. That is all I will say. I have enjoyed it from the start but now I wish I had the time to read it all the way to the end in one sitting.

Inna Hardison, co-owner of Ha Media and former publisher of Palm Coast Lifestyles magazine: I know I’ve complained about Lee not quite getting to the point soon enough, and so some hundred or so pages in, we seem to finally be getting somewhere, closer to the discovery of Atticus as a racist we all knew he’d be revealed as before setting out on this strange journey. Yet, there was something pathetically weak permeating what should have made me feel outraged for Scout. From the disdainful grab on the “Black Plague” pamphlet to her sweaty slipping hands at the colored balcony of the court house while listening to the standard-issue bigotries spewed by Mr. O’Halon, to finally the melting of the ice-cream, vanilla, naturally, and her upchucking the contents of her delicate, lady-like stomach.

Inna Hardison, co-owner of Ha Media and former publisher of Palm Coast Lifestyles magazine: I know I’ve complained about Lee not quite getting to the point soon enough, and so some hundred or so pages in, we seem to finally be getting somewhere, closer to the discovery of Atticus as a racist we all knew he’d be revealed as before setting out on this strange journey. Yet, there was something pathetically weak permeating what should have made me feel outraged for Scout. From the disdainful grab on the “Black Plague” pamphlet to her sweaty slipping hands at the colored balcony of the court house while listening to the standard-issue bigotries spewed by Mr. O’Halon, to finally the melting of the ice-cream, vanilla, naturally, and her upchucking the contents of her delicate, lady-like stomach.

Her reactions or rather non-reactions to what she is witnessing are as lifeless as the damn buildings sweating in the heat as she trudges shakily down the familiar streets that no longer want her. If I am to just disregard the rather blatant tells from Lee on the physical state of our heroine and pay attention to what she does and how she does it – Scout comes across as uneasy, not devastated or disgusted or mad as hell. There is no fight in her, just a longing to run from inconvenient conversations, it seems, drown her sense of no-longer belonging in her vanilla cone. I am still hoping for this currently-foreign to me Scout to punch somebody in the face or at the very least scream bloody murder at her unflappable aunt, at Hank, at anybody. But I suspect she’ll do nothing more than vomit delicately and feign sickness for the rest of the book.

Bill McGuire, Palm Coast City Councilman and management consultant: In this chapter we begin to move into some semblance of a genuine plot that is interesting and compelling. There’s the usual blathering in the household, which seems to introduce each chapter, this one between Alexandra and Jean Louise after Jean Louise discovers some racist propaganda and learns that Alexandra is perfectly okay with it. About that time, Henry arrives to pick up Atticus to attend a Sunday afternoon meeting at the City Hall. Jean Louise, curious as to the nature of the meeting, goes downtown and slinks into the courthouse. There she sees a meeting of a group of citizens who are staunch segregationists, although they are never identified as members of the Ku Klux Klan. She is stunned to see her father as the chairman of the group, which spews racial hatred and his guest speaker, one Grady O’Hanlan, who is as committed a racist as was ever made.

Bill McGuire, Palm Coast City Councilman and management consultant: In this chapter we begin to move into some semblance of a genuine plot that is interesting and compelling. There’s the usual blathering in the household, which seems to introduce each chapter, this one between Alexandra and Jean Louise after Jean Louise discovers some racist propaganda and learns that Alexandra is perfectly okay with it. About that time, Henry arrives to pick up Atticus to attend a Sunday afternoon meeting at the City Hall. Jean Louise, curious as to the nature of the meeting, goes downtown and slinks into the courthouse. There she sees a meeting of a group of citizens who are staunch segregationists, although they are never identified as members of the Ku Klux Klan. She is stunned to see her father as the chairman of the group, which spews racial hatred and his guest speaker, one Grady O’Hanlan, who is as committed a racist as was ever made.

After watching these goings-on for about a half an hour, Jean Louise leaves, stops by the ice cream parlor that used to be the family home, and attempts to calm herself down with some ice cream. Clearly, she is upset that her father and her boyfriend are both committed segregationists. I have a few questions about where this plot is going. How is it that, having grown up in this city, Jean Louise doesn’t have a taint whatsoever of racial prejudice? I can’t believe that her time in New York served as an ablution to her Southern upbringing.

My experiences in the city of New York are that most native New Yorkers are neutral when it comes to racial prejudice, New York itself being a melting pot of various races and cultures. It seems to me that most children are impervious to racial hatred-they get it from the grown-ups in their family. My experience at age 13, when blacks were first integrated in the public schools with white children in St. Louis, was a good one. I was assigned to work with a black student named Benny, we became good friends from that time through high school, at which time he joined the Army. As a high school student during the beginning of the civil rights movement in St. Louis, Missouri, I could probably write a short book myself on how society changed and how I observed the goings-on of the community during these times of strife, but I’m here to review a book. The good news is that I am interested in where this book is going now when, often times, I was tempted to throw it out the window. Maybe there is some skillful writing awaiting me as I proceed forward from chapter 9.

Brian McMillan, columnist and executive editor of the Palm Coast Observer:Of all the chapters so far in this novel, this is the one that can most appropriately be read as a legitimate sequel to “Mockingbird.”

Brian McMillan, columnist and executive editor of the Palm Coast Observer:Of all the chapters so far in this novel, this is the one that can most appropriately be read as a legitimate sequel to “Mockingbird.”

Jean Louise sneaks into the courthouse–the same courthouse where she watched her father courageously defend a black man 20 years earlier–and now sees the opposite: Atticus is participating in an organized effort to undermine segregation. How can this be?

It is more disturbing if you have read “Mockingbird” than it would be if you hadn’t. Jean Louise has a flashback to the scene of her as a child, but it’s not necessary. The scenes of her in that balcony are such a part of the canon of American literature that they might as well be part of our memories as well.

The magnitude of Jean Louise’s disappointment and shock are felt by the reader. That is not easy to accomplish in a novel, and it’s a scene that, even though it’s still a draft with some clunkiness, can be considered art.

Mary Ann Clark, founder of Flagler Reads Together and president of the Flagler County Historical Society: Following a leisurely after-church lunch, Hank and Atticus leave to attend a meeting. Jean Louise discovers the Black Plague pamphlet and learns the men have gone to a Maycomb County Citizens’ Council meeting, an organization she had no idea existed. Her curiosity and disbelief propel her to follow them to the courthouse where from the familiar balcony she listens in disgust to the segregationist talk. Nausea overcomes her, and she staggers outside and wanders in a fog to the place their old home once stood. She cannot believe her father could support the ideas of Mr. Grady O’Hanlon. The “watchman” is coming from the shadows.

Mary Ann Clark, founder of Flagler Reads Together and president of the Flagler County Historical Society: Following a leisurely after-church lunch, Hank and Atticus leave to attend a meeting. Jean Louise discovers the Black Plague pamphlet and learns the men have gone to a Maycomb County Citizens’ Council meeting, an organization she had no idea existed. Her curiosity and disbelief propel her to follow them to the courthouse where from the familiar balcony she listens in disgust to the segregationist talk. Nausea overcomes her, and she staggers outside and wanders in a fog to the place their old home once stood. She cannot believe her father could support the ideas of Mr. Grady O’Hanlon. The “watchman” is coming from the shadows.

Pierre Tristam, editor of FlaglerLive: To borrow a page from Smitty’s notebook, I think it’s time for this:

Pierre Tristam, editor of FlaglerLive: To borrow a page from Smitty’s notebook, I think it’s time for this:

This is the chapter where we discover that Atticus Finch is not much different than a member of the KKK. Rather, he’s our friendly upstanding Grand Wizard, a white supremacist who once defended Tom Robins not because he had any sense of obligation or love for the black man, or even for maid Calpurnia–who brought him the case–but because he wanted to salve his own conscience as a lawyer, knowing that an innocent man could be convicted of an offense he had not committed. He was upholding his beloved legal system, the very same legal system that enforced white supremacy, the same system that he now, as a member of the Maycomb County Citizens’ Council, he was defending against de-segregationists. He defended a black man to oppress him with a clear conscience.

It’s Atticus’s bigoted coming out, but it’s also a chapter where we discover in glimmers what this novel might have been, had Lee had the skills to pull it off, and what watered-down rosewater “To Kill a Mockingbird” became, when sanitized of the real side of Atticus. Those Mockingbird flashbacks may well have been Harper Lee’s way of lulling the reader into self-satisfied back-patting, a self-satisfied absolution for whites, when what she actually intended was to set a trap: to enable us to claim to see ourselves in the well-meaning, upstanding Atticus, only to spring the trap and make us see that we’re deceiving ourselves, that we are more Atticus than Atticus: that bigotry runs deeper, and that absolution doesn’t come that easy. But I suspect that’s wishing too much of a Harper Lee who seemed to have been more comfortable with her Antebellum South than not.

Jean Louise watching the scene in gehenna from the courthouse balcony, from the same spot where she’d watched her father defend Tom Robbins, should be the most powerful part of this novel so far, but mostly for what Mockingbird was never allowed to become. It does make Mockingbird look like barely half the story, or at least a child’s version of a much greater, darker story. The darkness wasn’t Boo Radley. It wasn’t even Ewell, who raped his own child. It was Atticus. That’s Jean Louise’s discovery on that balcony, if we can believe that she’d never known her father’s tendencies before. Our discovery could be just as shattering in a literary sense, assuming something central was denied Mockingbird. It was certainly crafted into a very good book. But it appears to have been eviscerated of its deeper intent, though neither Jean Louise as a character nor Harper Lee as a writer seemed in either Mockingbird or Watchman capable of carrying that intent to term. There’s a third, unwritten book in all this: our projection of what might have been written.

Stylistically the chapter is still among the weakest. The writing is shoddy and overdone, the characterizations borrowing more from caricatures than real people. Harper Lee’s presence is much too pronounced. For Jean Louise to make this bleak discovery only now, after annual visits to Maycomb, after growing up there as an adolescent and a young adult, is beyond asking us to suspend disbelief, unless the chapter is an experiment in science fiction, or Maycomb had a Love Canal-type drenching, with amnesia the result. But there it is. In this chapter, that’s almost beside the point.

Leave a Reply