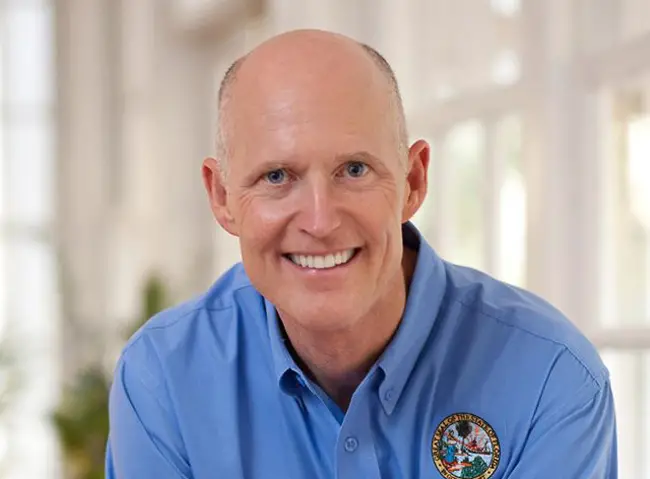

In many ways, Rick Scott is still an enigma.

When he burst onto the scene more than four years ago, Scott was unknown to the majority of Florida voters. Any who did remember him likely had only a vague recollection of a TV pitchman opposed to President Barack Obama’s health-care law or, for those with longer memories, as the former chief executive of a company that wound up paying one of the largest fines for Medicare fraud in American history.

It was the former that helped propel Scott into a political life for which his skills and his instincts often seem ill-suited. It was the latter that political opponents have continued to use, more than 15 years later, to tarnish Scott’s reputation and to try to convince voters that he can’t be trusted.

Four years after his election, Floridians still have a mixed, at times almost-contradictory view of their governor, now running for a second term. The tea-party darling who won an election promising to slash spending but now boasts of the largest education budget in state history. The candidate who ran vowing to crack down on illegal immigration but later pushed the Legislature to approve lower, in-state tuition rates for undocumented immigrants. The outsider who has learned to play the inside game in Tallahassee well enough to get many of his legislative proposals approved.

“Who are you, really, Rick Scott?” asked then-Attorney General Bill McCollum in 2010, when the two were locked in a tight Republican primary.

Four years later, it’s not clear that Floridians have any better idea than they had when the question was asked.

That uncertainty has produced dueling images as voters head to the polls. In the telling of Scott’s campaign and allies, he is a not-always-smooth politician focused on creating jobs while learning the intricacies of his own. To opponents, he is at heart a corporate raider looking to close one final deal before returning to the hard-edged conservatism that drove him to near-historic lows in public popularity early in his term.

Which portrait voters believe could determine whether Scott wins a second term in November or becomes the first governor in 24 years to lose a bid for re-election.

THE PERSONALITY OF RICK SCOTT

During a speech at the Republican Party’s annual fundraising dinner in September, Scott quieted the crowd by saying that he had an announcement to make.

“Charlie Crist is a slick politician, a smooth talker, and unfortunately, I’m not,” Scott said, to laughter and applause.

In that statement, a governor not known for introspection laid out as well as anyone the differences between himself and his opponent, former Republican Gov. Charlie Crist, now running as a Democrat.

Crist is almost universally known as a man perfectly at ease glad-handing at campaign events and talking to anyone, from constituents to lawmakers. Even political opponents say they come away from meetings with Crist feeling good.

In contrast, Scott comes across as distant and aloof. Things that come naturally to other politicians — highlighting the contributions of a member of the audience — seem almost forced coming from Scott.

“He’s just not a standard, slick politician,” said House Speaker Will Weatherford, R-Wesley Chapel. “He doesn’t want to be.”

The truth, friends and associates say, is a bit more nuanced. To be sure, Scott’s public persona is not necessarily a radical departure from his private personality: businesslike, intense and focused.

“My experience is that Rick Scott around the dinner table is the same Rick Scott we see at Cabinet meetings,” said Senate President Don Gaetz, R-Niceville. “He’s not running for Miss Congeniality. He’s running for chief executive.”

Almost everyone who has worked with Scott says his work ethic is impressive. The governor needs little sleep, sets out detailed goals for each day and works relentlessly to achieve them — something that was apparent even during his initial run for office in 2010.

“He really was wearing out the 20-somethings who worked on the campaign,” said Susie Wiles, who managed the 2010 campaign.

Scott also has a sharp memory. He often easily rattles off detailed economic numbers during news conferences. Brian Burgess, who worked for Scott in the crusade against Obamacare starting in 2009 and was the governor’s first communications director through 2012, said Scott can give someone an assignment, not see them for three weeks, then ask them at their next meeting whether the task was completed.

“The guy never forgets anything,” Burgess said.

Some of those who have worked with Scott don’t dispute the image of him as distant. In her autobiography, “When You Get There,” former Lt. Gov. Jennifer Carroll wrote that despite trying, she never developed a close relationship with Scott. Carroll wrote the book after resigning — she says under pressure — in 2013.

“During my entire time in office, I never received a birthday card or an anniversary card or anything that showed a personal touch,” wrote Carroll, whose resignation came amid controversy about her past ties to a major player in the Internet café industry.

But others say the governor can be kind and thoughtful behind the scenes. Burgess recalled a time that his son and another aide’s daughter were having a birthday party at a Tallahassee establishment.

Scott’s SUV appeared, and Florida Department of Law Enforcement officers accompanied the governor into the party. Burgess had not expected Scott to attend.

Wiles said the governor looks out for those he cares about.

“It’s never loud or necessarily even overt, and it’s never anything he wants people to know, but his kindness is enormous,” she said.

That can extend to his work with others in Tallahassee as well. Gaetz’s wife, Vicky, uses a wheelchair — and the senator said that any time the two visit Scott, a small ramp is set up to make it easier for Vicky Gaetz to get into the Governor’s Mansion, and that the governor will ask her in the course of an evening whether he can help her with something.

“When we come to the Governor’s Mansion, it’s been unspoken, it’s been friendly, but there’s always been this accommodation,” Don Gaetz said.

It’s the kind of thing that would be almost expected from most politicians, but with Scott, it seems almost noteworthy — a signal that the man once lampooned by the Tampa Bay Times editorial board as the Tin Man from the Wizard of Oz does, indeed, have a heart.

THE EDUCATION OF RICK SCOTT

Mike Weinstein, who served in the House and was one of the first elected Republicans to support Scott during the 2010 GOP primary, was sitting with the governor-elect at an airport shortly after the general election. Scott was telling Weinstein, who left the Legislature in 2012, that the public would see how Scott intended to govern when he submitted his first budget proposal to lawmakers.

Weinstein said he chuckled that Scott didn’t seem to realize “that his budget really didn’t matter,” because House and Senate leaders would look out for their priorities first in the negotiations over the spending plan.

The discussion between Scott and Weinstein foreshadowed what would become an early theme for the governor’s administration: At first, Scott didn’t seem to grasp the difference between being the chief executive of a company and the chief executive of a state.

“There were a lot of growing pains in there,” Burgess said.

Scott set the tone in his inaugural address: The new governor still saw himself as an outsider.

“The truth is, he who pays the piper calls the tune,” Scott said. “Now we’re going to call the tune, not government.”

Still, the governor tried to reach out to the key players. A week after he took office, he met with Senate Republicans at Andrew’s 228 Restaurant in downtown Tallahassee and expressed confidence about the coming session.

“I think this is going to be a lot of fun,” Scott said. “And I think it’s going to be a lot of fun because I think we’re going to get a lot of things done.”

There were many adjectives later used to describe the 2011 legislative session. “Fun” was not one of them. The conclusion of session dissolved into chaos because of a feud between the House and the Senate, which didn’t adjourn until almost 4 a.m. the day after the session was scheduled to end.

In between, Scott further alienated an already-suspicious press by putting velvet ropes in front of his podium at one news conference to keep reporters from following him; angered African-American lawmakers by trying to relate to them based on his growing up in public housing; and drew a letter from then-Senate Budget Chairman JD Alexander suggesting Scott might have broken the law by selling state planes — a goal Alexander supported.

Scott’s focus on jobs also rankled some lawmakers who said he took it too far. The new governor used “job” or “jobs” 31 times in his first State of the State address, but ran into opposition when he tried to get rid of programs in his office dealing with drug control and adoption — which Scott said duplicated other agencies and didn’t help his focus on the economy.

“I commend him for wanting ‘jobs, jobs, jobs,’ but he has (a) whole array of things for which he is responsible and … which he must support,” said then-Sen. Evelyn Lynn, R-Ormond Beach.

In later years, Scott would explain his obsession with jobs in personal terms, talking about the financial struggles his family faced as a child.

“Not having a job is devastating to a family,” Scott said during his 2013 State of the State address, according to the prepared remarks. “I remember when my parents couldn’t find work. I remember when my dad had his car repossessed.”

Eventually, Scott got most of the policy changes he wanted from the Legislature in 2011, though they were often pared back. Pension changes Scott signed were not as sweeping as what he wanted; his corporate tax-cut request was completely reconfigured to have a dramatically smaller price tag; and Scott’s push for a crackdown on illegal immigration and a two-year budget were not adopted.

THE EVOLUTION OF RICK SCOTT

In later sessions, the governor would scale back his ambitions, pushing for one or two major priorities. And lawmakers would say he grew into the role, no longer seeing the Legislature as a corporate board of directors that would quickly line up behind Scott’s ideas.

“The Florida Legislature is made up of 160 people with about 200 different opinions on any given issue,” Gaetz said.

By 2014, Scott was able to use his bully pulpit to help push through a bill granting cheaper, in-state tuition rates to some undocumented immigrants who had been in Florida for years. He enlisted two former Republican governors — Bob Martinez and state GOP icon Jeb Bush — to push for a Senate committee vote. When the committee refused, Scott’s team summoned reporters to his office so that he could demand action.

“We’ve got to give these children the same opportunities of all children,” Scott said. “Whatever country you were born in — whatever family or ZIP code — you ought to have the chance to live the dream.”

Scott had not started out as a strong supporter of the bill. In fact, years earlier, he had voiced opposition to similar legislation. But the Senate eventually caved, and Scott later signed the bill into law.

“That bill would not have passed the Senate if it wasn’t for Governor Scott,” said Weatherford, who first made the proposal a priority.

Opponents, of course, have a more unsparing opinion of the governor.

Incoming House Minority Leader Mark Pafford, D-West Palm Beach, summed up the lessons of the past four years this way: “When you run on tea-party principles, you can destroy a state in four years.”

And Scott’s shifting opinions on the tuition bill and other issues — including education funding and his support for an unsuccessful proposal to expand Medicaid in Florida — haven’t convinced Democrats. They have no doubt that the governor is still an ideologue, but one who is doing what is necessary now to get re-elected.

“The most frightening thing that we should all think about is if this guy gets re-elected, he goes back to being the true Rick Scott that he is, which cut education to the bone, destroyed our environment, wouldn’t fight for the middle class, doesn’t believe in raising the minimum wage,” Crist told reporters recently. “I mean, it would be a nightmare.”

But supporters say Scott is now in the fight of his young political life precisely because he has, by and large, stuck to his principles.

“The irony is that his popularity isn’t so high,” Weinstein said, “but he’s done exactly like he said he was going to do.”

–Brandon Larrabee, News Service of Florida

OrlandoChris says

By far, this is the easiest voting decision I have ever made in my

lifetime.. Adrian Wyllie, you have my vote. Also, Bill Wohlsifer

No on 1

Yes on 2

No on 3

Thomas Kelly says

Ask yourself this question…Is Florida better now than it was four years ago? The answer is obvious. Reelect Scott!

Carl says

The only reason its better is because Obama got us out of the war and created jobs , Rick Scott could of created 250.000 more but like all Republicans he`s an obstructionist, the rail system isn`t good for him and his Greedy oil friends, and I guess medicaid could use a good robbing again so he didn`t expand that , wants that safe full when he cracks it THIEF!!!!!

Indie says

It may be better for Thomas Kelly, but it isn’t better for Charlene Dill.

Carl says

There is nothing unkown about this thief, he robbed medicaid for 184 million dollars, he hates the sick the disabled , poor and elderly , he`d euthanize them all if he could , he cost the state at least 250.000 jobs vetoing high rail system and refusing to expand medicaid , guess there`s more money there he has ear marked to steal , he`s a piece of inhuman excrement, anyone who votes for this man needs their head examined