Weldon Ryan is an unfinished work. That could be said—it should be said—of any artist, though with Ryan the unfinished is a literal pattern of life and work strangely at odds with the paintings he does finally put on exhibit, which do everything possible to look finished, polished, as close to photographs as he can make them—sometimes, and paradoxically, at the expense of the artistic expression underlying them. It’s something he learned in his years as a cop sketch artist, when nailing perpetrators, not making them sympathetic, was his art’s objective.

Weldon Ryan, 2011 Artist of the Year:

- The Weldon Ryan retrospective opens Nov. 12 with a free reception from 6 top 9 p.m. and runs through the month at Hollingsworth Gallery, located at City Market Place, 160 Cypress Point Parkway, behind Walmart, in Palm Coast. Call 386/871-9546 for details.

Realism can reveal as much as it can mask, so it’s not surprising, given the patterns of Ryan’s method and his artistic trajectory, that some of his most revealing work is a series of half a dozen large paintings on a rainy theme that depart from his usual representation of absolute precision and meditate instead on the meaning of storms. One painting in particular, which he considered not only unfinished last week, but failed, too, and not ready for showing, looked more like one of his best: the look from inside a car of a tree-lined street, in heavy traffic, in a heavy rain (Ryan says the image is based on a scene at Belle Terre Parkway heading south of State Road 100). The whole frame is caged in low-hanging dark-grays, as if clouds are an extension of the very same car protecting you from their drenching, with a single, thin exception: along what appears to be the dashboard (but doesn’t have to be), Ryan painted a stray, uneven red line, giving the entire scene a subtle, beautiful jolt. It’s extremely difficult, and rarely tried, to give life to banal scenes in Palm Coast—a city that has yet to find its meaning, let alone its soulful places. That’s what Ryan manages in that painting.

Yet he doesn’t like it. He hasn’t even titled it, and it may (unfortunately) not be on display tonight, when a Weldon Ryan retrospective opens at Hollingsworth Gallery in conjunction with the Gargiulo Art Foundation naming Ryan the 2011 Artist of the Year.

“I had this notion that it was a just a nice scene, I wanted to fade things out, and it just didn’t work for me, this painting,” Ryan said in his studio earlier this week, where he’d been spending untold hours finishing work for tonight’s opening. “I’m probably not going to put it in because I still have more work to do. I like my work to be realistic. It wasn’t going that direction. I realized I had more work and more research to put into it to make it more accurate. And so I decided to suspend my work on this and pick up something else that was flowing.” To this pair of eyes, it was precisely what Ryan considered the lack of research and accuracy—that lack of last-ditch realism—that lent the painting its reality. That’s apparent in the rest of the series, too.

The Ryan Method

Leaving work behind is a habit: “I have a whole lot of unfinished paintings, I’ll be honest with you. The reason is, I might be sparked by an interest and I might start it, but if it’s not flowing and something else comes in play, I’m like a kid in a candy store. I want to get to the next greatest thing. So I leave a lot of work behind. I usually pick up on it once I find something interesting. But for now, with this particular situation, and wanting to have some new things, I decided to prepare six large panels, and I took a whole bunch of photographs, and we had the rain spell. It was great. Everyone else was upset that it was raining. But me, it was like, this is great, look at the rain, look at the beads of raindrops or the water coming off the windshield. I just loved it, and seeing the clouds and how angry it was at times and the opening of the clouds—it was just so dramatic. I decided this is the direction I want to go. So I took all this research photos during that time. Naturally, with the six panels, I decided to do all six pieces at the same time.”

Like his paintings, Ryan doesn’t talk in riddles. Nor is he interested in using the sort of language you’d find in glossy art magazines when discussing his art and various jabs at getting something done. “This is what I do,” he says. “It’s like, you know, you throw it to the wall and see what sticks, what hits your motions, what makes that connection with you, and then you go to it and you work on that piece. Sometimes I start something that I have a total affinity for and I carry it through.” Sometimes not.

He’s been taking that approach in his life, too. “He’s constantly evolving,” says Richlin Ryan, his wife of 20 years.

They were married at the Brooklyn Botanical Gardens, four years after another one of Weldon’s attempts at throwing something up on a wall and seeing if it’d stick. That one took place at Urban Outfitters in Greenwich Village, where Richlin was working. Weldon was looking for freelance work as an illustrator. “And this strange artist walked in that I didn’t know,” Richlin says. “It was pretty amazing because I was working there and he walked in and gave me a promotional piece. I guess you were looking for work at the time.”

“Yeah, I was pounding the pavement in New York City, looking for freelance work,” Weldon says. And hitting on beautiful women through his art. He gave Richlin a self-promo piece called “Cracked Up.”

(© FlaglerLive)

“I was going out to dinner with some friends that evening and I couldn’t stop staring at the piece, because it was so powerful,” Richlin says. “This is a great artist, I mean, his work was amazing. I don’t even think he was at the stage that he is right now, but the work is so amazing and I kept staring at it. And of course that evening after I had dinner with my friends, we spoke on the phone ‘till 2 a.m. We had the same music in common, so many things. We’re both from the Caribbean, big family, single mom, separated parents.” Richlin’s family is from Guyana.

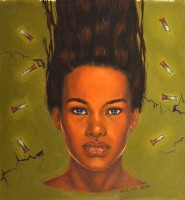

The painting is the portrait of a beautiful, full-lipped woman with otherworldly bluish eyes and a mane of dark hair jetting up. She is rimmed by a halo of crack vials, and a cracked green background. The piece was painted at the height of New York City’s crack epidemic. “I saw the devastation of my neighborhood,” Weldon says.

Richlin hadn’t at the time picked up on the vials. “My focus was on the main image which was this beautiful woman with her hair shooting up. I was looking at the skills and how well he rendered the image. I think it was years after you actually explained the piece to me and I go, ‘are those really crack vials?’”

“This is years after she listened,” Weldon laughs.

The irony of such a painting bringing the Ryans together would hit them later, too. But what Weldon threw on the wall that day in the Village absolutely stuck.

Weldon Ryan’s journey began in the largely unfinished atmosphere of Trinidad and Tobago 49 years ago, where he was born in the middle of a pack of three boys and three girls to Pentecostal preacher father and a stay-at-home mother who first detected his artistic skills. The family emigrated to the United States in May 1969, landing at Kennedy Airport in New York and spending the next few years in the South Bronx, one of the most dangerous—challenging might be the more polite way of putting it—neighborhoods in the city. His father, with whom he’d later have a falling out (they haven’t spoken in a decade), took up work as an orderly in a hospital, his mother worked for Ma Bell (AT&T’s grandma), and his eyes worked the street from his upstairs apartment, since he was not allowed to play at street level, whether in the Bronx or in east New York in Brooklyn, another one of those tough neighborhoods, where the family moved. Two fires in the Ryans’ tenement in a single week forced the family to move.

Riding New York City’s Crime Wave

It was back to the Bronx after that Brooklyn year, right by the Bronx Zoo, when crime in New York was hitting a historic high. “From where I was upstairs in my fourth-floor apartment, I would look out and see people getting robbed, people going to the Bronx Zoo unsuspecting. We had a few bad elements. Finally they got their just desserts. And me being naïve, thinking, hey, somebody else is getting picked, I didn’t think of anything.” He was going to New York’s famous High School of Art and Design at the time, and doing some growing up along the way. “There was a lot of violence, a lot of my friends were killed because of crack cocaine. I was on the phone with you one time,” he says, looking at Richlin, “and someone got shot outside the window. I heard the popping sound and I peeked my head out and saw what was happening. The guy, his name was David, he ran upstairs, he lived in what we called the Green building, we were in the Blue building, so he got off on the fifth floor, and we had a two-level apartment. I went to see what was happening with him, and there was a trail of blood leading to his apartment. I followed it, and he was lying there, bleeding to death. He was shot I think three times.”

Flagler Artists of the Year:

|

And yet for all of Ryan’s desire to be an artist—he wanted to be a commercial artist in college—here’s what he did after college and all those bloodied years in The Bronx and Brooklyn: he took the civil service exam and became a street cop. He was assigned to some of the city’s worst neighborhoods, including Washington Heights and Harlem. That was before those neighborhoods’ 1990s renaissance, Harlem’s especially. He took to it. He now describes it as being “indoctrinated,” but he liked the work, too, with his partner Jackie, who helped him center himself and learn the beat.

“I was so against it,” Richlin says. “In my mind, I said, there goes the artist. I think we had a conversation. I was like, you’re not going to be that sensitive artist person. You’re going to be a police officer. That’s completely the opposite of who he was. ‘Oh no, it’s just a job.’” He loved the adrenaline rush. He loved the danger and the excitement. And he did change, to the point where he discovered that it was a matter of picking up the paint brush again or risking his sanity.

“I helped a lot of people, but there was a situation where you’re chasing people with guns and seeing people die in front of you, seeing all kinds of nasty stuff,” Ryan recalls. “I saw one kid he was actually crushed by a tractor trailer, and his midsection was squashed, and he’s still breathing and looking and wanting help. That was depressing. Seeing kids with what we call moving walls, cockroaches: you turn on the light, the flashlight, and all you saw was roaches on the wall, kids living there. It was just devastating seeing these kinds of things. I tried to give mouth to mouth to one kid, actually it was a baby, a few months old, I tried, she was still warm, so I thought that if I could do some CPR on this kid, she might make it. But the baby didn’t make it. She was a few months old. She had a cold. Her mom didn’t know how to take care of her. She asphyxiated on her mucus. That was probably the clincher that I had to start doing something other than—to keep my mind off of police work.”

Return to Sources (of Sorts)

Even then, the art depended on his precision skills, and the sort of skills that required the artist to hide emotions under the glare of imagined line-ups of one, as police sketches are. “So I guess the whole notion of throwing it to the wall and seeing what sticks applies to that too,” he said of his success landing the job.

Ryan held the position for almost a decade, until 2004, but mid-way through he was injured during a scuffle with a suspect, tearing up the meniscus in his knee and preventing him from going out on police details—and cutting short his ability to stay on, as he had originally wished. By 2004, Richlin had lost her job as the art director at a magazine—she was cut while on maternity leave. Richlin’s mother had moved to Palm Coast in the 1990s, on Postman Lane. The children (the Ryans now have two girls and a boy), after successfully lobbying for another brother or sister, would spend their summers in Palm Coast, and would lobby their parents the rest of the year to move permanently to Florida. Richlin became a lobbyist, too.

One day Weldon got home and announced that the family had one month to pack up. They’d be moving to Palm Coast. And so they did, arriving there on Christmas Eve, 2004.

Stations of Ryan’s Cross

But as has generally happened in Ryan’s life, what has stuck, and for all his impatience with serendipity, has usually been the result of that mixture of luck and experimentation, or daring, that brings his paintings to life. He walked down a few doors to Hollingsworth Gallery, where his encounters with JJ Graham, the gallery owner, have had some of the same centering quality as his encounters with Jackie, his one-time cop partner, and of course Richlin. It’s been all art since, in the comfortable confines of his backroom studio at the gallery, where the unfinished finally has the permanence and acceptance of a home.

He sums it up this way: “You know we had Dumbo, Down Under the Manhattan Bridge Overpass, and that was our art outlet at the time, it was the art happenings in New York City at the time, that was the new SoHo, and really getting the position I did with the art league, and finding this oasis, and getting involved with JJ as well as the Gargiulo Foundation, it kind of made me understand I do have a mission here, and one of the things is to help create or be a part of this movement that we can have in the growth of art in Palm Coast.”

This is Ryan’s latest “wave of enthusiasm,” his latest throw at the wall.

Stories like this typically create an arc, and often a contrived one to fit the reporter’s narrative of a beginning, middle and end. If that’s the impression here, it’d be misrepresenting Ryan. He’s not at an end point at Hollingsworth, though he’s finally at a place where his work, his art, is not second billing to something else. This is what he is now, a full-time artist, at work. For the first time. As that series of six paintings suggests, there’s no end point here. It’s more of a resumption. “I want the satisfaction of being noticed,” he said at one point, explaining what he meant by the “power trip” that his realism gave him.

He’s been noticed. He’s the artist of the year. But there’s a lot more yet to that work in progress, on and off the canvass.

Jim Guines says

In one eveing, I met Weldon Ryan formally and shook his hand, I saw his work I just fininshed reading a work of art about him in the above piece, All I can say, what a hell of a guy, I can’t wait to see what he does next..

Laura says

When humans get it, the idea of process,

the possibilities are limitless.

In process mentality, humility quietly enters into the picture and makes lots of room for

stumbling

fumbling

getting back up

no shame

self-forgiveness

picking up where you left off

or moving on to something or somewhere else.

Thanks for sharing Weldon’s mini bio in such attentive detail.

His obvious awareness of process in his own life is creating something beautiful

in the art world and in his family.

Palm Coast’s own process will beam with innovation because the Ryan family lives there.

{{* *}}

PJ says

Weldon’s art is awesome and is a great choice for Artist of the year! Nice work Weldon!

J.J. Graham says

What a great article about a great friend.

PJ says

JJ this type of honor is all because of your efforts to bring culture to Palm coast and flagler County. Keep up the good work.

w.ryan says

Pierre is a great artist. What a painting he has painted of me. It’s no wonder how seeing his painting helps me to understand myself much more than I did before. I’m in a great place with great people which has helped me in my creation of art. Any thing I can do to further the arts in Flagler and through out I will do. Thank you Pierre! Thank you all!