| Skip introduction and take me straight to today's installment. An introduction to American Impressions: I was the luckiest reporter on the planet. I’d proposed to my editors at the Lakeland Ledger to send me across the country and write an essay on each of the 50 states. They went for it, handing me two credit cards, a camera and the vehicle of my choice--a Chevy Venture I rigged up with a library and a bed.  I spent 15 months alone on the road, logging 60,000 miles and four times as many words. The result anchored a weekly section throughout 1999, counting down to the millennium. What you’ll read here between Christmas and the New Year, when FlaglerLive traditionally pulls back on hammering you with hard news (and hammers you instead with pleas to support us), are the first few installments of that journey. While my reporting at the time forms the basis of the work, most of what you’ll read has not been published before. The rest has been extensively reworked and updated. I spent 15 months alone on the road, logging 60,000 miles and four times as many words. The result anchored a weekly section throughout 1999, counting down to the millennium. What you’ll read here between Christmas and the New Year, when FlaglerLive traditionally pulls back on hammering you with hard news (and hammers you instead with pleas to support us), are the first few installments of that journey. While my reporting at the time forms the basis of the work, most of what you’ll read has not been published before. The rest has been extensively reworked and updated. I was not traveling to discover myself or get away from myself, I was not in search of America or of eternal truths. I’m not equipped for that sort of thing, being rather shallow, and I wasn’t going to pretend to understand a state or even a village from a passing week. Nor is this a travelog about food or fun places to visit or quirky people I met along the way. I was just a reporter, picking up stories here and there, choosing for each state one or two themes that struck me as telling about that part of the country, and hoping to build a mosaic of an America every inch a wonder and a puzzle of joys and sorrows to an immigrant hopelessly in love with his adopted country, despite and still. I hope you’ll enjoy the journey. --Pierre Tristam Previous installments:1. Introduction: The Day Before America | 2. Heartland | 3. The Road | 4. Alaska: The New Suburb | 5. Alaska Highway | 6. Montana: Backtracking Lewis and Clark | 7. Montana: Ghost of the Prairie | 8. North Dakota: A Life in Missiles | 9. South Dakota: Crazy |

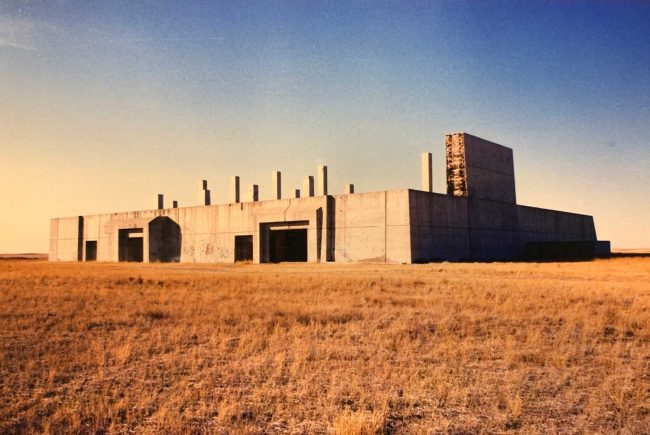

It rises from wild grasses in Montana’s Golden Triangle, at the western extremity of the Great Plains, a massive hulk of concrete the shape and size of an abandoned ziggurat. To the innocent this thing makes no sense. It shouldn’t be here. There’s nothing for miles around but the faint outline of the rockies to the west, farmland and fallow fields everywhere else. It’s not a house, it’s not a mall, it’s not a factory. It’s not anything recognizable, and there’s something otherworldly about it.

I should say there’s nothing visible for miles around, but look closer to the ground as you drive two-laners like Ledger Road, Depot Road, South Camp Road. You begin to notice barbed-wire enclosures that also don’t belong, that don’t make sense, because there’s hardly anything inside, but that probably have some relation to the ziggurat. They’re flat enclosures with strange protuberances, unusually thick concrete slabs and rude, threatening warning signs.

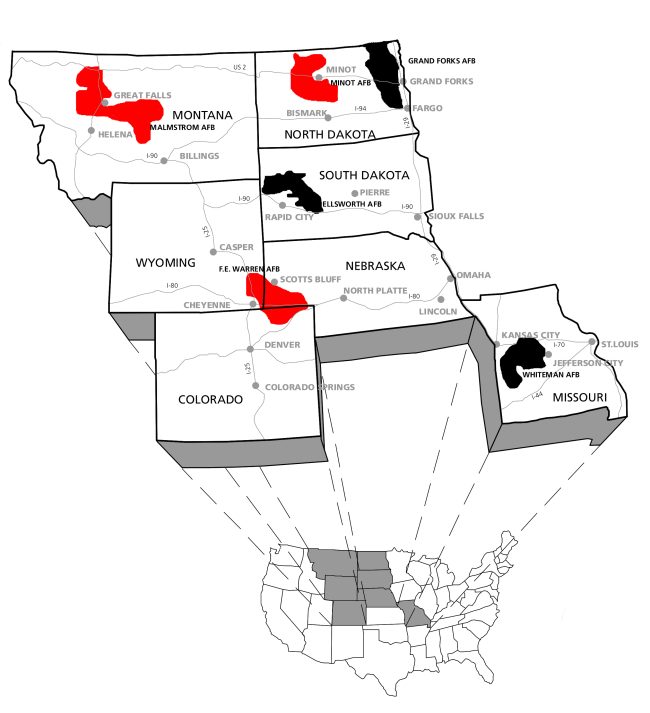

They’re Intercontinental Ballistic Missile silos planted in what’s rustically referred to as a “missile field.” Why not? Western Montana grows dry beans, flax, safflowers, squash, alfalfa and ICBMs. This field is part of the 564th Squadron attached to the 341st Missile Wing at Malmstrom Air Force Base. Each of these silos contained a Minuteman III, each equipped with a warhead of 300 to 475 kilotons pointed at a Russian target up to 6,000 miles away, each with the destructive power of 15 to 30 Hiroshimas.

I’d see these enclosures here and there, stop, stare, take pictures, then stare again and forget where I was, hypnotized. On the Alaska Highway a few days earlier I’d felt at times as if I were at the end of the world. Here, in one of the most sublime places on earth, I was standing on the end of the world. It would only take a Strangelove order and the flip of a switch.

It was an odd detour from my original aim in Montana: to backtrack as much of the Lewis and Clark trail as I could. But was it a detour? Their Corps of Discovery had carried the most powerful military arsenal to ever breach the region. These silos were rooted in precedent.

Lewis and Clark left not one trace, not one campsite, not even a cairn. Even if the silos were all decommissioned, as most have been, even if they were bombed out, as they still could be, that strange ziggurat of concrete and steel off Ledger Road would outlast every blast and every civilization to come as surely as Mesopotamia’s 6,000-year-old ziggurats have survived every empire since. America’s Great White Fathers would leave their mark one way or the other.

*

The ziggurat was part of a dubious Army project called Safeguard, the building itself called by one of those military terms that, like the military, make zero sense: Perimeter Acquisition Radar, or PAR. Capt. Yossarian would have appreciated it.

It was to be rimmed with Spartan or Sprint missiles that would intercept enemy nukes, presuming that a 53-inch warhead going 7,000 miles an hour could intercept a warhead a few inches larger, going 5 miles per second. When originally conceived in the 1950s PAR was to be one of 17 like it positioned near cities and missile fields and serving as the eyes of the country’s antiballistic missile system, a forerunner to Ronald Reagan’s equally doomed star wars program–the Strategic Defense Initiative that would have deployed lasers and missiles to shoot down Soviet death stars. That was back in the cold war when wars were so much fun that life was a zero-sum game.

An unusually lucid Congress had its doubts about Safeguard’s effectiveness. Amazingly, so did the Pentagon. So did science fiction buffs who liked a touch of realism that stopped short of reinventing the rules of physics. The system was that insane. It’s one thing to shoot down a couple of missiles sputtering at a few hundred miles an hour: iron dome delusions persist even now. It’s another to take on a blizzard of missiles and decoys incoming at Mach 24.

Over the years 17 PAR sites were whittled down to 12, then to two as justifying arguments like national security or saving the children lost their glow. There was always the fail-safe of unstoppable waste: jobs.

In 1969 the last two sites, in Montana and North Dakota, were at the center of a fierce battle between Congress and the Nixon administration. The Senate split 50-50 on a bill that would pup up a few billions for construction. It took Vice President Spiro Agnew’s nattering bobhead to break the tie and clear the way for the project. It’s good to know that facts mattered back then about as much as a president’s lawlessness.

“Defense Department studies, obtained by the Foreign Relations Committee,” The New York Times reported a year later, “indicate that the Perimeter Acquisition Radar, which provides preliminary tracking information, and the long-range Spartan missile ‘serve very little if any useful purpose’ in providing defense for the Minutemen bases.”

Of course, construction proceeded, starting in April 1970. The site needed nearly 1,500 acres, including easements. The government paid farmers a pittance to seize their land. There were weather delays, labor disputes, cost overruns, and innumerable false promises to the communities of Montanans watching the monster rise from the plains.

Then, overnight, construction halted. There would be no more PAR in Montana. Pack up, everyone, and decamp. Forget the new roads. Forget the new infrastructure. Forget the permanent jobs. It was August 1972. Nixon and Brezhnev had just signed the Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty. It limited the United States and the Soviet Union to one anti-ballistic missile facility each.

Hence the look of a ruin built as one.

It was about 10 percent done when work stopped. It would have been 128 feet high, with 17 million pounds of steel bars and 58,000 cubic yards of concrete, its five stories and 160,000 square feet of space resting on a concrete pad 11 feet thick after the displacement of tens of thousands of cubic yards of dirt. The wall facing north, where Soviet missiles would be incoming, was to be 7 feet thick, inclined at 25 degrees and bearing the radar’s single eye, a phased-array of 6,888 antenna elements that would have made it look like the eye of a gigantic fly. The building would have had its own underground power plant, buried fuel tanks, a heat sink, a community center, segregated enlisted and officers’ quarters and dining complexes, a dispensary and a gymnasium. Blueprints leave to the imagination where servicemen would have shot up heroin, lost their marbles and blown their brains out.

Conrad, the nearest town worth the name, was projected to grow by 5,000. Then the Army changed its mind. It would build a new town of 417 housing units near the PAR site, promising a big boost to nearby Ledger, and another of 240 units at its sister missile facility a few miles away, boosting Conrad. Neither happened. Instead, the region got a couple of new roads and a better sewer system to process the bricks everyone was supposed to be shitting when the PAR site was up, plus an eyesore or a monument, depending on which way you look at it. That was it.

The Nekoma, N.D., PAR was completed, only for its mission to shift away from sci-fi almost immediately after completion. It was converted to bland, unneeded satellite-tracking, as if to give it something to do. I was going to visit the completed North Dakota site several days later.

But here I was, where not so much as a no-trespassing or any kind of sign gave a hint about the history or meaning of this building. The government had stripped the site of as much material as it could, burying roads and demolishing all accessory infrastructure. Otherwise it seemed as indifferent about the ruin as it had been about its functionality.

For all that, the structure I was staring at was no less breathtaking. In my book of monuments, it is one of the seven wonders of America.

*

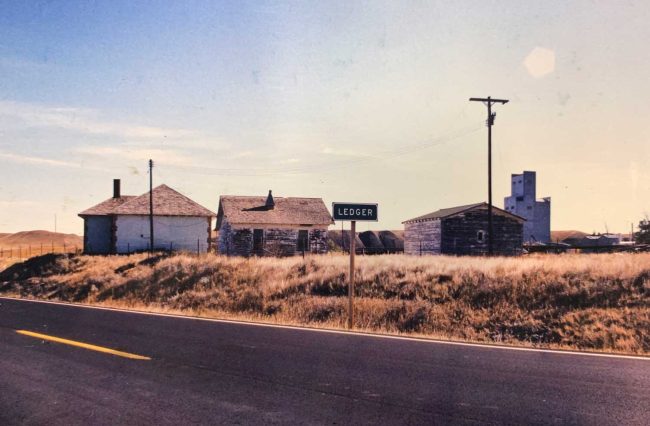

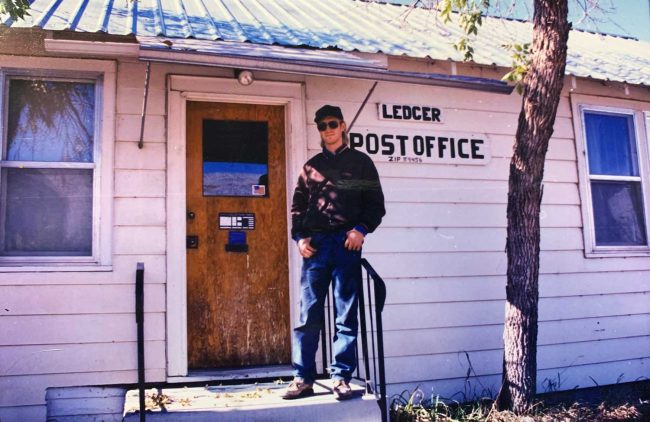

It wasn’t the only ruin around. There is nothing along Ledger Road except the small town of Ledger (pop. about 12), a missile control station eight miles further, and the PAR site another eight miles hence.

I counted a dozen buildings in Ledger, including three abandoned houses and a row of shacks, two grain elevators (one abandoned), a small barn, a post office (zip: 59456), a community hall (closed), and three trailers. Also, 11 dogs, two horses, a few sheep and a rail line. A sign in front of one grain elevator said, “Please do not park your seed truck in front of Morano’s house.” It’s the sort of place where Star Trek could have filmed an episode: the crew beams to a place eerily like Earth but not Earth–who on earth would build such a thing as a PAR–and Spock spends half an hour with his tricorder trying to figure out where those faint hums of humanoids are coming from.

When I knocked on one door, Peggy Morano answered. She stood in the doorway answering questions as her husband of 32 years, Frank, a retiree of the mustard business, sat inside. They spoke English of course, as everyone does in the entirety of Star Trek’s universe.

“We were the only ones here for several years,” Peggy said. “My son liked driving snowmobiles and three-wheelers. He couldn’t do that in town, so we bought out here.” “In town” means Conrad, nine miles south on I-15.

“Another lady that was here died when she was 102. She was here 45 years. Her name was Freda Hall. She was a postmistress here when the mail used to come on a train. We have quite a mail route that comes out here still. At one time there was a saloon here and a store. Someone was telling me that a long time ago there was Indian tipi rings out here. But then they run cattle through.” It was, after all, Blackfeet country. Today’s southern boundary of the Blackfeet Indian Reservation ends 20 miles east of Ledger along the banks of Birch Creek, a tributary of the Marias River.

Sam Lee, 52 when I spoke to him, lived in the trailer nearby with his wife and two daughters. A third daughter, Melissa, 19, lived in the third trailer with Kent Habets, 23. Kent and Melissa planned to marry that Nov. 21. Melissa was due to have a child on March 10. When Kent brought the mail to his future father-in-law, Sam was talking about his seven years in the Marines (1964-70), his years in Vietnam, and PTSD– post-traumatic stress disorder.

After the Marines Sam had been a truck driver, “hauling things around to missile sites” that were planted in the Montana plains, a job he found senseless in many ways because the military buried millions of brand new spare parts it didn’t need (nuts, bolts, washers of all sizes). He’s not fond of the government. He fights it. “There’s over 50,000 names on a monument in D.C. That was senseless too. That’s what I find hard to swallow. We’re angry at the government over PTSD and we’re losing,” Sam says as he opens one of the envelopes. “This is what this is here, probably.”

There was about as much sense in Sam Lee going 8,000 miles to Southeast Asia to fight a losing war and bring back untarnishable traumas as there was in that mass of concrete and the loony tunes that made it rise a few miles down the road. It’s difficult to have much respect for a government responsible for either.

Sam read, grunted twice, folded the letter back in its Department of Veterans Affairs window envelope, then changed the subject. “I got no patience with people. This is the closest to town I’ve lived since we’ve been married, 22 years. You can stretch your legs out here. See, this is an unincorporated town, so if we want we can raise elephants out here and they can’t say anything about it.” I don’t think he meant a white elephant.

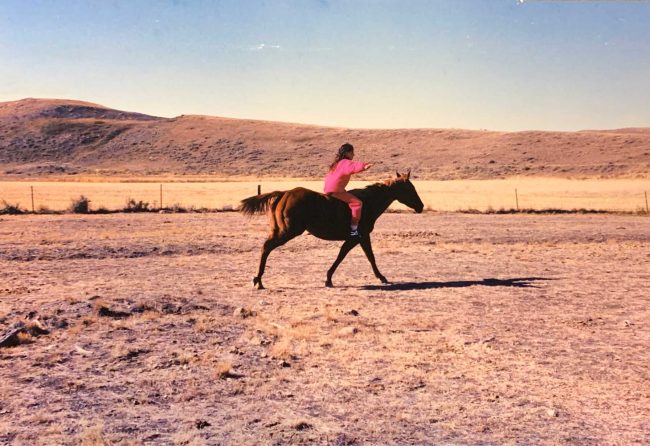

As he spoke his 11-year-old daughter, Kayla, rode her horse almost to a gallop, without a saddle, her hands outstretched like wings.

Kent Habets was to be the future of Ledger, if he decided to stay there with his future bride. They moved into a trailer last March. “If everything works out we might have our wedding here,” in Ledger’s community hall. He was a welder at Intercontinental Truck Body, which built van bodies for General Motors 12 miles east of Conrad — a good job in a part of the country where social security checks tend to outnumber paychecks. He didn’t mind life in Ledger, his trips through San Francisco, Vancouver, Spokane and Portland enough to tell him that cities aren’t for him. He preferred to work on restoring a 1957 Chevy Stepside and get his doses of big-city adventures by way of his father-in-law’s satellite dish. (He eventually moved to Conrad with his wife.)

He was as aware of the nearby Lewis and Clark trail as of the nearby missile silos, and as indifferent — two neighboring elements of national history and importance that people have come to live with without thinking about. The silos have stopped generating jobs, the trail never did. “Every year we have the whoop-up trail days in Conrad,” Kent says. “About 85 percent of the town gets together to celebrate Lewis and Clark. Most everybody is drunk by the end of the weekend. That’s about all it is anymore. It gives people a chance to go out and get plowed.”

*

I had interviewed half the population of Ledger. The other half was out for a stroll (it was a Sunday), although its car pulled in just as I was pulling out. The sun was getting lower. I wanted to spend the night on the grounds of the PAR.

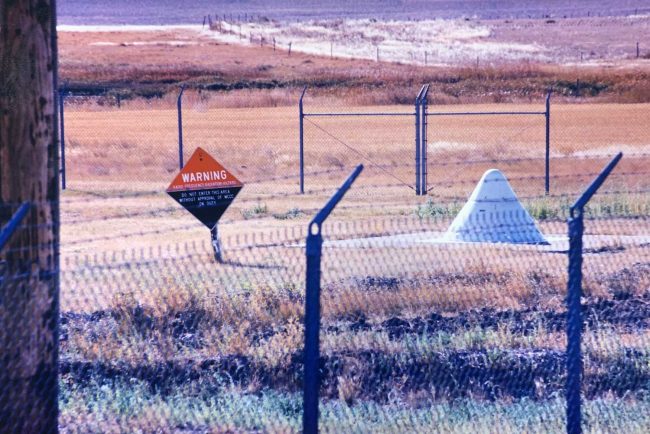

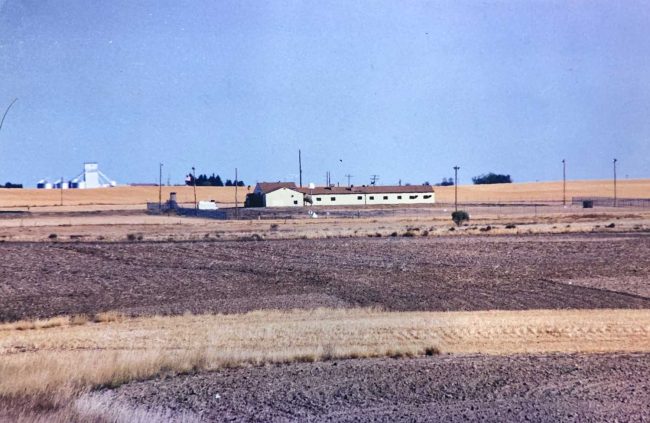

On the way, I stopped by “Q-O,” a missile launch control site by the side of the road. It looked like an average suburban house of yellow walls, windows, brown-shingled roof, a regular, ugly television antenna next to the sort of antennas used by ham operators, an American flag flapping in the wind, a basketball hoop in the driveway, a picnic table, three litter barrels, at least six sewer heads, a pond nearby with 16 black ducks floating idly.

Of course it’s not a suburban home. The windows were one-way mirrors. The fencing around the property was topped with rows of barbed wire slanted outward, and the No Trespassing signs scream No Compromise: “WARNING RESTRICTED AREA — It is unlawful to enter this area without permission of the installation commander Sec. 21 Internal Security Act of 1950; 50 U.S.C. 797. While on this installation all personnel and the property under their control are subject to search. Use of deadly force authorized.” It almost felt like Florida.

In a corner of the property two dozen yards from the house sat a white cone in the middle of a concrete slab. The warning sign there was different: “Radio frequency radiation hazard. Do not enter this area without approval of MCCC on duty.” (I looked up the Superbowl 1300 numeral on the web to figure out the acronym, but could only come up with the names of community colleges and an old Sims video game.)

I took the cone to be the missile and snapped several pictures, my hands just shy of shaking and my mind reeling with thoughts of my proximity to a 335-kiloton thermonuclear warhead. I was wrong. I was later told (and saw) that missile sites don’t come with the nice suburban house and basketball hoops. They’re mere barbed-wire enclosures of grass, light poles, and a thick concrete slab in the middle that either slides open or gets blown open by a TNT charge so the missile can rocket its way out.

What I was looking at near Ledger was a command center to which every 10 missile silos are connected by thick reinforced underground cables and by radio communications, should they lose underground capability. The white cone was just a fancy antenna, probably putting in double duty to pirate ESPN’s signal, or or whatever softcore porn was tumbleweeding across the prairie at the time.

What I took to be sewer heads were circular transmitting and receiving antennas as well. Like Ledger road, the site looked deserted, but that, too, was an illusion. As a command site, “Q-O” were permanently manned by at least two officers ready to enter their ten missiles’ target codes at a moment’s notice and turn the key (two keys, actually) to send them on their way, even in this post-Cold War age.

The classic illusion is that the missiles are not “targeted” at Russia, by agreement. But it isn’t as if the missiles were ever pointed in a particular direction other than heavenward. Their target is embedded in a set of numbers which can be changed in seconds. Other than the southernmost island of New Zealand, America’s and Russia’s ICBMs can be targeted to reach every inhabited spot on the globe. The targeting takes a few seconds. The missile’s journey to its target takes, at most, 25 minutes, about as long as I stood at arms’ length from the fencing of “Q-O,” unaware that all the while the two officers underground had me in their sight, probably as much excitement as they’d had in a month.

*

The 564th Missile Squadron was “deactivated” in 2008, the missiles and their key-turning attendants removed from their silos. Each silo was left vacant over the next eight years then demolished and filled in with concrete after 2011. I don’t know if it was intentional. But when the wing’s public affairs office published the story signaling the last of the silos’ destruction, it did so on Aug. 6, 2014, the 69th anniversary of the crime against humanity commonly referred to as the bombing of Hiroshima.

“Lt. Gen. Stephen Wilson, Air Force Global Strike Command commander, and Col. Tom Wilcox, 341st MW commander, watched as Launch Facility T-49, located approximately 25 miles west of Conrad, Montana, was demolished,” the Wing’s John Turner reported. “At around 9:30 a.m., contractors used heavy machinery to bury the site’s 110-ton launcher closure door and fill the launch tube with dirt, making it forever unusable as a missile launch site.” The demolitions were required by the latest version of the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty with Russia, which also allowed Russians to verify the demolitions for themselves.

Don’t be too nostalgic: The United States still has 400 ICBMs planted in Montana, North Dakota, Nebraska, Colorado and Wyoming. They’re in the middle of a $1.5 trillion modernization program. It’s still called deterrence. It’s been working, in the sense that it’s the sort of thing that will always work as long as we’re around to know it. The day it stops working will be our last.

*

I reached the PAR in low light and drove through one of its openings. Inside, it was a nesting ground for prairie swallows and bobcats, maybe even bears. The concrete slab was covered with white birds’ feathers, gravel, rotting pop bottles, bolts, mud, and in one corner of the building the decomposing skeleton of a good-size quadruped. Swallows swooped out in frightening attack formations from hidden crannies in the ceiling. Looking past the forest of concrete pillars in another corner something had burrowed, nest-like, in a huge pile of dark-gray loam. I didn’t get close to investigate.

Ordinary people don’t get to speak their minds on the marble walls of great monuments. Graffiti is the revenge against the prohibition. “Aim high,” “you bit the big one,” “Not responsible for loss or accident.” “Mindie is a lesbian.” “Barry is gay.” “Barry can’t swim.” “Barry is a big girl.” “Ban this.” I took pity on Barry, who could not possibly have had much of a fun life.

Over the years the graffiti has become more elaborate. The walls are a defacto museum for Pondera County’s high school students, who seem to use the grounds for weekend entertainment. Others use the building’s walls for target practice. The array of 6,888 antenna elements never made it, but it’s been outdone by more than 6,888 bullet marks. Animals mark their territory with pee. Human animals do it with bullets. The support pillars were all encased in faded yellow steel, some of them bullet-marked. On one pillar, the outline of a man had been spray-painted, named Dick (I assumed for Dick Nixon), then drilled with 41 bullet holes that barely marked the steel. Carbon-dating the bullet holes might have put them back around late 1972.

There were a few Nazi signs, somehow always in call-and-response tandem with outlines of dicks and balls. “Your mom is evil.” “Shelby cops suck shit.” “Go Pat Buchanan.” “Long live Jerry garcia.” “My husband didn’t get my cherry but he still uses the box it came in.” “1989 D S Forever,” the D S Forever part written inside a heart. It was that blend of the unique and the universal, a chorus of voices suddenly howling their existence louder than the wind of the plains on that late afternoon of demented swallows. But I got the spooky feeling that I was in somebody’s sanctuary.

There was no one around for miles. But I grew uneasy. I drove back out and parked outside the structure, the light falling fast. I pulled a short distance from the PAR, maybe 100 yards. I watched the outline of thick walls lose that softening evening glow and become shadows against the distance, then become more ghostly under a waxing gibbous moon a day short of full. I could still make out the ragged edge of the rockies to the West.

These are the plains a white man saw for the first time on the moonlit night of July 27, 1806, as Meriwether Lewis was galloping away from hostile Indians–either he or the men he was with had just shot and killed two Blackfeet–“through a beautiful level plain” and past “immence herds of buffaloe all night.” I wondered what he’d make of the PAR, or the inverted silos in the ground, if he could detect them. Lewis was a man of the Enlightenment, but he wasn’t much for the absurd.

I’d decided to spend the night there, in communion more with Lewis than the PAR, nonexistent buffalo and excess concrete notwithstanding. The wind fell with the night and the plain took on the appearance of an endless dark-wool blanket of calm, dotted faintly in the very far distance by electric lights that could be confused with very low stars. I was as alone as could be, no cell signal, no electricity hookup, but for once, nearing the 30th day of my journey, I didn’t feel the loneliness of the road. The day’s contrasts had been too much, the surrounding warheads too near. Even the structure didn’t look the gloomy black I had expected but milky white under the moon, a leavening so at odds with its cemented angles and bolts of steel that will outlast the life of the solar system.

I didn’t dare anymore get very far from the van, didn’t for one second dare walk back into the PAR. The land made me feel equally awed and foreign. People here are scarce and the climate doesn’t hesitate to remind them why. I read again Lewis’ entries from his expedition to the Marias River and back, then at about 10 p.m. heard on the only A.M. radio channel I could catch a local news-break announcing that grisleys were expected to forage further east of the Rocky Mountains than usual, as the huckleberry crop had been a poor one this year.

I laughed, even though I was only a meridian’s hair east of the Rockies. An hour later, well shuttered against the cold inside the van and minding my own business with a can of mushrooms for a late-night snack, a blood-curdling growl a few inches out the window shook the mushrooms out of my hands. It was sudden, deep, curt, the thing emitting it as if right up against a window. I was too freaked out, too panicked to look for anything but the keys, to turn them–ignition!–and to decamp much as Lewis and his men had out of Blackfeet country.

I traveled in a few minutes the 10 miles it took him half the night to travel. Back on deserted Ledger Road I cussed a few times to calm my nerves. I wasn’t interested in making the drive to Conrad and risk running into the authors of some of those graffiti. There was only one alternative. I scouted a cozy gravel turnoff within sight of the missile control center’s yellow floodlights. And I spent the night there, in the safe epicenter of three megatons of nukes.

![]()

Laura Shaver says

I talked my husband into moving into a RV and living on the road for a few years. The best way to meet the real people of the US.

Found out quite a lot about our country during those years.

About 8 or 9 hours South of your story on the road to Yellowstone from Big Horn Canyon in Wyoming is a place called Heart Mountain. After the bombing of Pearl Harbor the US decided we had to worry about the Japanese that had been living lawfully in the US for several generations. We built a concentration camp in the desert, gave the Japanese in San Francisco 24 hours to gather a few belonging, loaded them in busses and imprisoned them. They had to leave their homes, their business, even their pets behind. After the war was over they handed them $5 and sent them back. Canada did the same.

It’s things like this that worry me so much.

If you get to go, take tissues, you can not read their stories without crying.

dave says

Fla has its on relic that ended in 1979 in the Everglades, the hm-69 Nike Missile Base at Research Road, Homestead, FL

Dr. Evil says

We all see and hear on the regular how Russia lies and deceives. So why should we believe for an instant that they honor their side of any nuclear arsenal agreement? I think we need more “deterence”. Complete with tri-fold brochures of exactly where they’re pointed, along with free 3-day, 2-night AirBnb style accommodations for any Russian official to view and tour so they can see precisely which warhead has their name on it.

Alan Baker says

Look nice!