| Skip introduction and take me straight to today's installment. An introduction to American Impressions: I was the luckiest reporter on the planet. I’d proposed to my editors at the Lakeland Ledger to send me across the country and write an essay on each of the 50 states. They went for it, handing me two credit cards, a camera and the vehicle of my choice--a Chevy Venture I rigged up with a library and a bed.  I spent 15 months alone on the road, logging 60,000 miles and four times as many words. The result anchored a weekly section throughout 1999, counting down to the millennium. What you’ll read here between Christmas and the New Year, when FlaglerLive traditionally pulls back on hammering you with hard news (and hammers you instead with pleas to support us), are the first few installments of that journey. While my reporting at the time forms the basis of the work, most of what you’ll read has not been published before. The rest has been extensively reworked and updated. I spent 15 months alone on the road, logging 60,000 miles and four times as many words. The result anchored a weekly section throughout 1999, counting down to the millennium. What you’ll read here between Christmas and the New Year, when FlaglerLive traditionally pulls back on hammering you with hard news (and hammers you instead with pleas to support us), are the first few installments of that journey. While my reporting at the time forms the basis of the work, most of what you’ll read has not been published before. The rest has been extensively reworked and updated. I was not traveling to discover myself or get away from myself, I was not in search of America or of eternal truths. I’m not equipped for that sort of thing, being rather shallow, and I wasn’t going to pretend to understand a state or even a village from a passing week. Nor is this a travelog about food or fun places to visit or quirky people I met along the way. I was just a reporter, picking up stories here and there, choosing for each state one or two themes that struck me as telling about that part of the country, and hoping to build a mosaic of an America every inch a wonder and a puzzle of joys and sorrows to an immigrant hopelessly in love with his adopted country, despite and still. I hope you’ll enjoy the journey. --Pierre Tristam Previous installments:1. Introduction: The Day Before America | 2. Heartland | 3. The Road | 4. Alaska: The New Suburb | 5. Alaska Highway | 6. Montana: Backtracking Lewis and Clark | 7. Montana: Ghost of the Prairie | 8. North Dakota: A Life in Missiles | 9. South Dakota: Crazy |

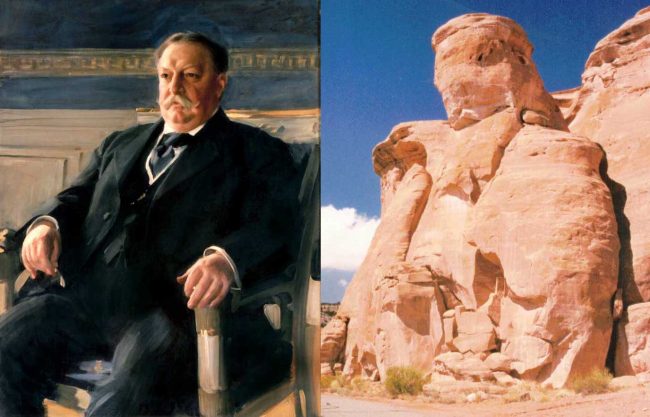

As you approach it from the north Colorado National Monument erupts in giant cliffs of red rock and canyon ramparts of unreal formations over the Colorado River Valley, as if Earth had grafted a playground from Krypton. You don’t need to peer into the Hubble or James Webb telescopes for clues on the creation. Its Precambrian dawns are right there, predating the Jurassic by a billion years. Colorado National Monument reminds us how larval human landscapes are in comparison.

Not that explorers and the Department of Interior let us get that far. They like to reduce everything to playpen scale and humanize the inanimate, to make it more relatable. So the genesis of floodplains and beach sands, of billion-year-old igneous and metamorphic rock, of millennial sandstone and shale and mudstone in unspeakably humbling uplifts are all reduced to Kissing Couples, The Coke Ovens and Independence Monument.

The naming can be cute. It’s certainly not offensive. Ignoring it is easy. But so much of our experience in nature is preconditioned by its reduction to human reference points, defeating the impulse to see beyond ourselves. We default to names on the trails map and leave it at that, just as we rarely leave the car or the trail to look deeper. How many people looking at Kissing Couples will stop there, maybe make a flighty reference to Klimt–another human-scaled reduction–snap a shot that might get 17 passing likes and move on to the next landmark, never seeing the formation for itself, in its own nameless context, speaking a language that predates the beginning of time?

The naming can also be irresistible. One of those rock formations, my favorite at the monument, looked weirdly familiar in my visits there. It rises by roadside Buddha-like, with a second-cousin resemblance to the statues of the Bamiyan Valley in Afghanistan before the Taliban demolished them. The bottom part has crumbled. No doubt the indifferent cutting of the road had something to do with it. (Imagine Edward Hopper rock ‘n roading this scene.) The torso and shoulder-like formations rise obesely toward a fat head resting on a chin of sandstone, the face looking stern and benevolent, depending on the light.

It finally hit me years later. It’s His Rotundity William Howard Taft, the president who declared the Colorado National Monument a monument in 1911.

I’d returned to the monument as a sort of pilgrimage within a pilgrimage. I’d been there six years earlier with my brother, the first time I’d ever been that far west. I just wanted to spend the night in the thick of junipers and the memories of that wonderful trip, though the difference between 1992 and 1998 was startling. In the summer of 1992 the country was emerging from recession. Vacationers were few, big rigs almost invisible, the campsite atop the monument (elev. 4,597 feet) a vale of snores when we reached it late one night.

I got there just as late this time. The campsites weren’t full of tents but of SUV’s, RV’s, massive campers, mini-convoys of SUV’s attached to campers, the people in them not yet snoring but probably still wearing their Vuarnet shades and Prada boots and saying words like “gear” and “bitchin,’” the hang-gliders among them all hot and bothered with visions of “thermals.” The stock market was up 40 percent in two years but the primitive campsites weren’t designed for so many assets and dividends. I’d come up here for the perfect quiet of the mountain but with gas at $1 a gallon, RV generators powering up satellite-linked televisions roared an oil glut symphony in waste major late into the night.

When I took a walk the next morning one site had its gear arranged as if to prepare for a Prussian military parade, dozens of “sports” water bottles lined up in even squares, coolers parked like Panzers ready to assault the mountain, sleeping bags piled as pillboxes. Not a soul in sight. The party must have been at morning calisthenics, listening to whoever was playing the part of Burt Reynolds in Deliverance preaching the latest in hiking wizardry. Most campers eventually left either to blitzkrieg the mountains or to go home and resume worrying about their nest egg, now called Nasdaq.

For all that, the conifer smell everywhere and the still, dry air, the gravel crunch underfoot, the canyon rim in the west gaping its invitation, still beat most places on earth at that moment. But the pull of the road doesn’t let up. I had my own bitchin’ gear and attacks to plan, with eight days to make it in time for the ferry in Homer, Alaska. By morning my van, a white Venture leased for $13,000, itself looked like an intruder amid the junipers, demanding to be driven.

I would soon develop a love-hate relationship with the van, cozy, demanding slammer that it was, as I did with the road–not in the abstract: the road in the abstract is where the romance purrs. I mean the actual grind of asphalt and concrete, of soul-crushing interstates and billboard canyonlands, of business districts in town after town outboosting each other with disfigured landscapes, of the dynamite-worthy traffic of primates pretending to drive while lecturing everyone else with that American literary classic on their ass: bumper-sticker morality.

*

“The American really loves nothing but his automobile: not his wife his child nor his country nor even his bank account,” a character in a late William Faulkner novel says. “Because the automobile has become our national sex symbol. We cannot really enjoy anything unless we can go up an alley for it.” The historian Peter Norton doubts it. The love affair, he said, is “one of the biggest public relations coups of all time. It’s always treated as folk wisdom, as an organic growth from society. One of the signs of its success is that everyone forgets it was invented as a public relations campaign.”

The car and oil and tire industries needed to prevent European-style public transportation like mass transit and rail from encroaching on their profits. The romance was manufactured into their products. Lewis Mumford in a series of essays for The New Yorker in 1955 saw in New York what would keep happening across the country: a demolition of landscapes and quality of life by the car and its support system.

“Were the eruption of vehicles and buildings in and around New York a natural phenomenon, like Vesuvius,” Mumford wrote, “there would be little use discussing it; lava inexorably carves its own channels through the landscape. But the things that spoil life in New York and its environs were all made by men, and can be changed by men as soon as they are willing to change their minds. Most of our contributions to planned chaos are caused by private greed and public miscalculation rather than irrational willfulness.” That was in 1955, when there were just 63 million vehicles on American roads. The number had more than tripled by 1998: my Venture was one of 211.6 million vehicles on the road. (We’re at 275 million now, 1.3 vehicles per adult.)

In invention then as in manufacturing now, the car was never a single country’s product. A Frenchman thought up the idea as a steam-powered hauler two decades before the French Revolution. A Scottsman made it electric 65 years later. A German developed the first internal combustion engine, another German powered it with gasoline, an American stuck a carriage on it and another pair of Americans–the brothers Charles and Frank Duryea–engineered the first car worth the name. What others conceived, America consecrated.

Whitman, Emerson and Thoreau were the first travelers. They didn’t need to go further than a pond or a lecture tour. They were all about the inward journey in the true sense of the greater jihad–the journey as personal self-discovery, as struggle with one’s soul and demons. Pistons took the introspection outward. Ford, Standard Oil’s tar babies and the Automobile Club of America democratized it.

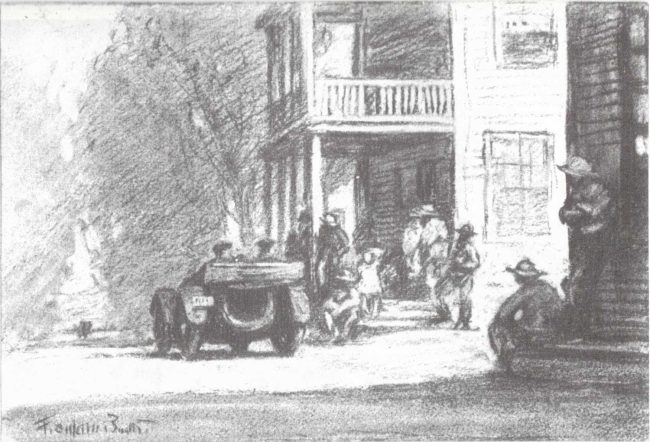

In 1915 Theodore Dreiser was throwing a party in Manhattan for a poet back when literary parties attracted reporters and illustrators. Among them was Franklin Booth, who drew for the Masses magazine, The New Yorker of its day before Woodrow Wilson’s revulsion for the First Amendment shut it down. Booth kept boasting about his 60-horsepower Pathfinder, then suggested to Dreiser to pair up on a 2,000-mile road trip back to their native Indiana. Dreiser immediately agreed: he’d write about it, Booth would illustrate. They crossed the Hudson two weeks later. Hoosier Holiday was published the following year, a 500-page classic for no other reason than for being the first American road book.

Like the car, the road book isn’t an American invention. What’s Homer’s Odyssey if not the first road book, the Mediterranean the first interstate? Julius Caesar’s memoirs could be read as travel books (veni vidi scripsi: I came, I saw, I wrote). Ibn Fadlan, Ibn Jubayr, Ibn Battuta: those were the true first travel writers, their prose pearling the breadth of Islamic civilization from its heights in the 10th century to its earliest declines in the 14th. Muslims, like early Americans–Indians across the Bering Strait, Puritans across the Atlantic–had the road trip programmed into their soul: the pilgrimage to Mecca kept them moving as Europeans didn’t, not until they got the itch to massacre Muslims during the crusades. But it’s surprising: We should’ve had Arab and South Asian Kerouacs by the score. The rare Jubayr aside, we have none. They don’t pray and tell.

You could wrap the planet many times over in the pages of travel literature written over the centuries. But the road book found its home in America. From Crevecoeur, Lewis and Clark and Tocqueville to Dreiser, Agee, the WPA guides, Kerouac, Nabokov (Lolita stylized the American road like no book before or since), Steinbeck, John McPhee, Larry McMurtry, Bill Bryson, William Least-Heat Moon and Robert Persig, to more hokey variations like Michael Paternity’s crossing the continent with Einstein’s brain in the back seat or Robert Kaplan and George Packer’s social diagnoses stopping just short of Cormac McCarthy’s apocalypse in The Road: the country’s geography, its astounding conformity of language and norms and laws, its relative safety is as if made to be crisscrossed as other continents cannot be. Where else could you travel thousands of miles in any direction and not encounter impassable physical or political borders? Where else could you get roadside convenience in golden arches from sea to shining sea? That, I think, is why the road experience and the road book are essentially American.

That, and American wanderlust. We’re an eternally dissatisfied nation, dressing up transience, ambition or greed as manifest destiny. “We move for a better job, a better house, better neighbors, better weather, better views,” the novelist Richard Ford wrote three years before I set out. “We move toward dominion and away from perceived dissatisfaction and threat. We move for curiosity’s sake. The continent itself makes us anxious. We move as a way of choosing action over the dreaded and uneaseful inward look. We move to escape our problems and, ever hopelessly, ourselves. Most Europeans I know — people who, indeed, almost never move — believe that moving is our national neurosis.”

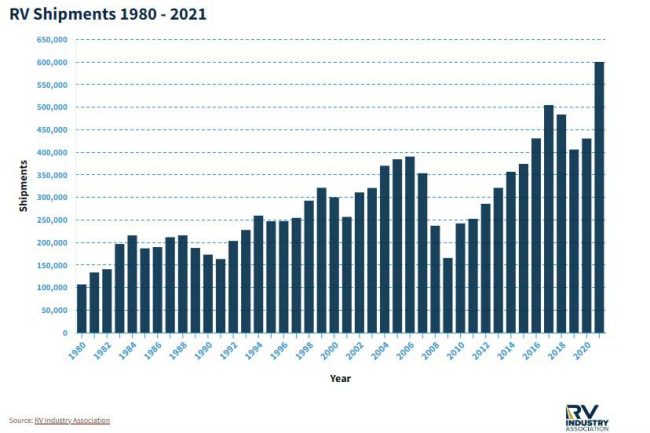

By the 1990s the country was getting older and moving less between homes, the Census Bureau told us. But it was more than ever on the road, increasingly with perverse means. With “motorhomes” that weigh up to 15 tons and burn a gallon of gas every couple of highway exits, it had found a way to take the splurge of single-family homes on the road: the RV Industry Association reported just 100,000 recreational vehicles shipped in 1980. The year of my travels, the number had tripled to 300,000, sending about a quarter of them to the Colorado National Monument in September. By 2021, it had doubled again to 600,000.

It was in Colorado and Utah where I understood why Bill Bryson had called RV people “demented.” The RV is the insufferable prick who blares private phone conversations on speaker at the cashier line, but at household scale, hogging the road, halving speed limits, quadrupling the gas guzzling and sloshing with the shitty presumptions of occupants oblivious to everyone and everything around them, including the pleasures of travel and deference to discovery–pleasures the RV’s steel cage prohibits. The thing is an imposition, an invasion, a waste. It is the trashy boomer’s ultimate fuck you to America, the national anthem sung by Roseanne, On the Road as lackadaddy garbage hauling. I wish I could have afforded one.

*

So here I was, behind a caravan of RV’s as long as a herd of cattle in a John Wayne movie, trying to fulfill my ablutions at Yellowstone National Park. John Muir said Yellowstone’s scenery “is wild enough to wake up the dead.” The traffic would have sent them back to their graves. I made the mistake of driving through the place. It was like driving through Manhattan at mid-day, when it takes an hour to go from First to Eighth Avenue. Instead of sky-scrapers, buffalo. Instead of shops, geysers. Instead of delivery trucks on every street-corner, campers and RVs blocking every lane. Instead of muggers, gapers and photographers who think nothing of halting their car in the middle of the highway because they see a buffalo. Amazing how often the buffalo seemed slimmer than their photographers. We exterminated the herd a hundred years ago. Now we’re the herd.

I had to stop to see Old Faithful. It’s pretty much illegal not to. You find a parking spot amidst that mall-like sprawl at Christmastime, walk the half mile to the spot, find a place among the thousands of spectators already claiming their inch of bleachers in a wide arc of bleachers around the geological formations, these “pots and cauldrons” that have been boiling thousands of years, to hear Muir say it, and wait for the next eruption, in the hot sun, with children crying in your ears and restless old folks shuffling under the weight of tourism’s burdens.

Lore has it that Old Faithful is as punctual as were Mussolini’s trains. It’s more like Amtrak, the punctuality something of a suggestion rather than a certainty. Dig enough into fine print and even the National Parks service concedes that eruptions happen like visits from the AC repair crew: anywhere in 35- to 120-minute windows. The geyser (the Icelandic word for gusher) only averages eruptions every 92 minutes. The average was much shorter over half a century ago, before the cataclysmic 1959 Hebgen Lake earthquake in West Yellowstone crashed half a 7,600-foot mountain–80 million tons of rock–into a canyon, created a new lake, killed 28 people and cluttered the pipes at Yellowstone. The average fell again after earthquakes in 1975 and 1983. These days, with climate change outdoing mountain crashes, scientists suggest Old Faithful may yet go dry.

Most of us dutiful gapers around Old Faithful’s mound had no idea that Yellowstone is the scene of 1,500 to 2,500 earthquakes a year, that some were taking place beneath us even then (most are hard to detect without instruments), that four or five miles beneath us was a roiling sea of molten and partly molten rock, of gas building the sort of pressure that heaves visible domes up and down on the surface, forming one the world’s most violent hot spots. We were lolling about inside the 50-mile-wide crater, or caldera, of a volcano that could explode at any moment with many times the force of all the nuclear warheads in the world, as it last did 600,000 years ago, as it unquestionably will again, covering most of the country in ash. That timing is less faithful: it could be this decade. It could be in 100,000 years. Fortunately, climate change may sink us first.

I was not the only media crampon there. A French crew from the emerging national network M6 was filming an episode of “M6-Kid,” a kids’ program airing every Wednesday afternoon since 1992. There was Nathalie Vincent, the little blond hostess as bouncy as she was made up, in take after take walking the length of the bleachers, with Old Faithful gurgling in the deep background, and with her Parisian French speaking through the Babel of Yellowstone to the good little kids of Avignon and Blois and Saint-Nazaire beyond the lens: “Et maintenant les kids, ouvrez bien les yeux car vous allez assister a un spectacle extraordinaire, l’éruption du Old Faithful, ce qui veut dire en français le vieux fidèle.” (“And now kids open wide because you’re going to see an extraordinary sight, the eruption of Old Faithful, which means in French, pas Clinton.”)

M6 was on location to film two weeks’ worth of episodes, the one in Yellowstone then another on a Wyoming ranch, where producers had found kid ranchers their eight-to-twelve demographics would love.

Here was Mademoiselle Vincent–who would go on to be a minor French celebrity–finally getting her lines right after the seventh take (a take for every crew member). Then she, too, waited for the eruption, and as she waited I spoke with Martine Houadec, in charge of production, who told me of her many trips to the United States, of how embarrassed she was to admit that she preferred Los Angeles over New York, of how impressed she was of the respect Americans showed for order and rules. “The French wouldn’t be like that, you know,” she said, lowering her voice as if other countrymen might hear her. “They’d be everywhere crossing lines, refusing to follow directions.”

Then Old Faithful erupted. So did Nathalie, toggling between looks at the gusher and into the camera. The heights of Old Faithful didn’t match her earlier description. Not quite 180 feet high, not quite two minutes, not quite roaring, but Nathalie didn’t let on. Nothing like television to make you dishonest: if it adds on the pounds, it can add on the height. “Come on, you can do a little better than that,” a weathered woman one-hundredth the size of Old Faithful and wearing a dark green t-shirt proclaiming the glory of Idaho yelled out, I assume to the geyser, not to the TV host.

“No, that’s pretty typical,” Tom Farrell told her. Farrell was the National Park Service ranger on duty that afternoon, M6’s guest star.

Old Faithful flushed and sloshed, peaked, meeked, hissed, steamed, peaked again a few times with orgasmic afterthrobs, then died his hourly little death. Muir in his day had been delighted by the crowds’ reactions, back when crowds were small enough and rules vague enough that there were no boardwalks, no barriers, nothing stopping tourists from venturing “near enough to stroke the column with a stick, as if it were a stone pillar or a tree,” and possibly get burned. Muir was there at the turn of the last century. Less than the blink of an eye, in geological time. But even then, Old Faithful was among the lesser gushers, with Castle Geyser and Giant Geyser exceeding it in force and heights. Castle now erupts only every 14 hours or so, to heights no greater than a fire truck’s ladder, and the Giant has gone dormant but for erratic memorial eruptions every few years. Americans prefer their wonders predictable. So Castle and Giant are ignored.

In this laboratory of nature, Muir wrote of Yellowstone, a park almost as big as Lebanon and as easy to get lost in, and taste the birth of the world, “Pots of sulphurous mush, stringy and lumpy, and pots of broth as black as ink, are tossed and stirred with constant care, and thin transparent essences, too pure and fine to be called water, are kept simmering gently in beautiful sinter cups and bowls that grow ever more beautiful the longer they are used.” But no one looks. No one notices the strange ozonated air, the rumbles of creation underfoot. For the masses of spectators around Old Faithful, the pictures were taken, the show was over, the attraction had nothing left to offer.

As if there was nothing left to see in that expanse of “most faithful evangel,” the bleachers cleared, the souvenir shop flooded, the RV engines revved up, and it was on to the next traffic jam. For a moment, but a moment only, the beauty around Old Faithful was uncaged from that mass of sight-snacking flesh.

*

The detour is ingrained in the American road experience, especially as our infrastructure decays. Detouring to Salt Lake a day earlier had been intentional: I was there to meet my parents, who were vacationing on a small tour of their own in the West–what would prove to be their last before the massacre of old age would overtake them.

We were to meet in Salt Lake, then again in Jackson Hole near the Grand Teton. There was an REI Outfitters I needed to get to in The Crossroads of the West, as its boosters like to call Salt Lake–with the same chimeric confidence that Bunnell calls itself the Crossroads of Flagler County–but it was more cross than road all the way, with a hint of racism. Road construction was a beehive of big digs, turning out of towners into mice in a labyrinth.

Residents seemed either ignorant of their geography or unwilling to give directions to a bleary-eyed man whose obsidian beard by then made him look more Semitic than usual. It wasn’t the first nor would be the last time that my appearance–always in direct proportion to the beard’s density–would trigger that look that has nothing to do with the apologetic “I don’t know” and everything to do with “go back where you came from.” (Just wait until we get to Minneapolis.) Then as now the country kept to the oath that its greatest terrorist threat would be exclusively Arab even after Timothy McVeigh, decorated and honorably discharged white-power veteran gunner of a recent war against ay-rabs, had sent a different message in Oklahoma just three years earlier.

With neither GPS nor a detailed enough map of The Calvary of the West I decided to call the non-emergency cop line, as much for direction as to preempt whatever sinister alert some other uncaffeinated caller I’d just scared might dial in. Hoping to trade on her sense of superiority I told the dispatcher I was a lost Floridian looking for REI.

Get this: she told me she’d have to radio the highway patrol so she could get directions. I was beginning to understand why the lost tribes had gotten lost in the first place. She put me on hold. She returned with a list of exit do’s and don’ts and a pilgrimage through a series of Temple streets and an avenue strangely called 3300 South. It all took me to the eastern edge of the city until, finally, I saw the double-peaked REI logo. I could exhale: This is the place.

I got taken for a $165 sleeping bag (not expensed) and a $19 tin cup (not expensed). I still had to find my parents’ DoubleTree Hilton.

Piggy-backing on their ritzier accommodations for a couple of days, first in Salt Lake then in Jackson Hole, was a nice break from the loneliness of parks and sordid motels, though Salt Lake was a cultural double-take. My mother was struck by the similarities between Mormons and Muslims as we sipped low-alcohol beer in a government-sanctioned speakeasy. Salt Lake is the Mormons’ version of the United Arab Emirates, with a third the value of Dubai’s sovereign wealth fund to boot, plus religion’s overt intrusions, as in Muslim theocracies, in public, private, economic and political spheres: The ban on liquor, the dearth of coffee and tea, the squalid history of racism and sexism, lingering echoes of the state’s curious sexual history, which is still evolving: bigamy was decriminalized in 2020.

It’s cliché, if not hazardous anymore, to write about Mormons’ peculiar institutions, even more so to write about Mormons’ sex drive. The PR juggernaut of the Church of Latter Day Saints is as formidable as AIPAC’s (the American Israel Public Affairs Committee). How else would the church have managed to transform “The Book of Mormon,” the satirical Broadway musical, into its own Exodus? So you trespass their catechism at your own risk.

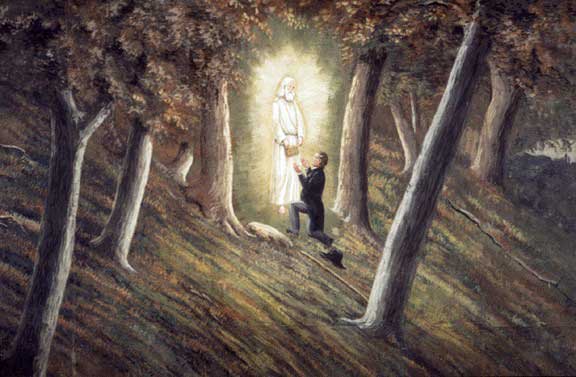

Nevertheless, Mormons’ cultural appropriation of Muslim myths can be arresting for their overtness. Joseph Smith’s “revelation” of the Book of Mormon was identically styled after Muhammad’s of the Koran. That was just a start. Smith was erecting temples in Ohio and Missouri in the 1830s when Protestant Missourians sought to prevent his flock from voting in the 1838 election. Smith again compared himself to Mohammed with a proclamation he inaccurately attributed to the prophet–“The Alcoran or the sword” and said: “So shall it eventually be with us, ‘Joseph Smith or the Sword!’”

Like all church histories–like all faith-based propaganda–this one is a bit suspect, too, and possibly the fabrication of Smith’s detractors, though Smith’s record of copycatting Islam supports it, and no less an authority than historian Daniel Boorstin reports it as fact. What’s not in dispute is the rabid persecution Mormons suffered at other Christians’ hands as their few survivors first decamped to Quincy, Illinois, and eventually to Utah, where to men’s delight and women’s bane, procreation was transfigured into an existential state of emergency.

With Mormons as with Muslims, bigamy is rare. The Mormon church officially disavowed it in 1890, wink wink. But it’s far from zero. Strip County, Arizona, used to be a particular hot spot for bigamy enthusiasts displeased with the church’s official ban. The interesting similarities and differences between Islam and Mormonism on that score were in doctrine, not in practice, the past tense sadly underscored.

Islam was vigorously liberal with regards to sexuality and pleasure for all involved: Sex was fun in Islam long centuries before Helen Gurley Brown tried to make it so for hopelessly repressed American women. Divorce was a Muslim woman’s prerogative the moment she was dissatisfied. For Mormon males, the bigamy was Muslim, the sex was more Calvinist work ethic: “We must gird up our loins,” Brigham Young, who’d fathered 56 children from 26 wives, had said of the great sacrifice, “and fulfill this, just as we would any other duty.” Good lord.

*

Prophets have a way of picking spectacular grounds for their works–the Buddha’s Himalayan foothills, Jesus’s Mediterranean idyll, Young’s Salt Lake. (Muhammad is an exception: Medina and Mecca are not exactly catnip for the eyes, which could explain his conquering wanderlust.) With the peaks of the Wasatch mountain range on one side, the tragically, increasingly late Salt Lake on the other, avenues that, when not bombarded with construction, recall the grandeur of Parisian boulevards, and that contrast of architecture between modern American and rococo theocratic, Salt Lake City is a delight of contrasts and contradictions.

The whiteness of the city can still be as blinding as Park City’s slopes (and skiers)–it’s maybe 2 or 3 percent Black, not by coincidence. Mormons weren’t exactly diversity’s wallflowers. The church officially ended its prohibition of Blacks in its priesthood only in 1978, when Church President Richard Kimball received one of those opportune “revelations” that, hey, bigotry is going out of style. Latinos and Asians are making quicker inroads.

As I extricated myself from the city again on my way to Wyoming I was expecting an awesome drive at the foot of the Wasatch Range. But the valley stretch through an endless run of Brighamist towns to the north mile after mile resembled the sprawls of malls and trailer parks and sudden cardboard subdivisions and apartment complexes of quiet desperation that infect the I-4 corridor. Flatten out the mountains and you’re as good as in Florida’ swamps. Utah’s state logo is “Still The Right Place.” I was never so glad to see Idaho (By Far The Better Place), to have been, as Francis Parkman put it, “delivered from the presence of such blind and desperate fanatics.” I don’t, like Parkman, mean Mormons. I mean developers.

And yet the blind and desperate fanaticism of the Right Place was sincere: you can’t argue with faith. The blind and desperate fanaticism of Jackson Hole and its surroundings–the Grand Tetons, Yellowstone–is of an entirely different sort, and sincerity has nothing to do with it.

Disney in 1993 announced plans for an amusement park themed around history on 3,000 acres near Manassas, Va., five months after Lorena Bobbitt had clipped and discarded her husband’s penis on the lawn of a 7-Eleven there. (There is no connection between the two events. I note Lorena’s act here because unfortunately no historical road marker ever will.)

It wasn’t enough that development had turned the area into what locals called “Manasshole.” Disney now had to rip it a new one. A New York Times editorial argued there was nothing wrong with that “in Anaheim or Orlando,” where “Neither place was ever known for its cultural or natural treasures.” But not next to the site of the two Battles of Bull Run, where 20,000 Union and Confederate soldiers lost their lives. “Disney’s America” was the 20,001st casualty.

No such objections appeared to have ever reached northwest Wyoming, exclusively known for its natural treasures. Jackson Hole was nothing but a dismal theme park, federated among the usual brands of America’s tourist traps and roadside atrocities. Ripley’s Believe It or Not. Images of Nature. Anvil Motel. The Merry Piglet Mexican Café. Trapper Inn. Wagon Wheel Restaurant. Wagon Wheel Laundrette. Two more of those in the next two blocks. Gift shops hawking “native” nicknacks made in Shanghai. Gift shops hawking “cowboy” nicknacks made in Shenzhen. Gift shops hawking gifts you could find in Anaheim or Orlando, made in Hong Kong. Traffic made in America, as always.

But the state is too big, too beautiful, too overwhelming to let these unmerry piglet sights matter so much. Once past northern Utah’s circuit of hell and into Wyoming, I don’t know how many times I had to stop the car–as I had in Western Kansas, as I had so many times in Colorado and even a few times in Utah–to calm myself down from the sheer beauty of it. Ugliness hurts. But beauty can be exhausting, too, especially when paired with memories the flip side of post-traumatic stress disorder, as when I’d cross villages with populations lower than the elevation and the word “Gulch” in them.

In Lebanon when we played cowboys and Indians just saying the word “gulch,” which must have sounded ridiculous in French, made us feel like we were mouthing a piece of America. As children, my brothers and cousins and I would play in the fields in the mountains, riding make-believe horses over brush and lizards and cobwebs, our own massive mountains naked of all their once mane-like cedars, and we’d shoot each other in Sam Peckinpah bloodbaths, never knowing, a) that the bloodbaths would surround us soon enough, and b) that so, too, would the chance to ride those very mountains, no longer make-believe, although not quite on horseback so much as in a company-provided minivan.

Here I was in disbelief at the memories’ resurrection and the state’s welcoming logo: “Wyoming, Like No Place On Earth.”

The following night I was kissing the ground of the Lewis and Clark National Forest in Montana, before the next day’s drive to the border. The old country in me expects that every time I come to a border I’ll see long lines, delays, barbed wire, guards dangling machine guns and posing intimidating questions. Our northern border is another wonder in my world, healing childhood traumas with the balm of the ordinary. It was undefended. I drove up behind a couple of cars. There was no one in sight at the American station. No one. At the station on the other side I had a conversation with a young Canadian armed only with a computer he held in his left hand, tapping my answers with his right.

“Where are you from?”

“Florida, Lakeland.”

“How long do you plan to stay in Canada?”

“About as long as it takes me to get to Alaska.”

“Are you carrying any alcohol?”

“No.”

“Any firearms?”

“No sir.”

“Have a good day.”

That was it. I was in Canada.

It was September 16. After the five-day crossing of Canada and the mud ruts wishfully known as the Alaska Highway, without a flat tire, without a cracked windshield or headlight, and with 12 hours to spare before the ferry to Kodiak, the midnight lights of Homer appeared in the distance, a finger of glimmers wading into the black waters of Kachemak Bay.

marlee says

I feel like I am taking the journey along with you….

including your dry humor and awesome photos ….

We used to travel across Country along that route in early Spring….

There were more tents than RV’s back then.

Janet Sullivan says

Oh, I loved reading this. Thank you.

What Else Is New says

A splendid piece. Thank you, Pierre. You always bring classic literati for a home in your pieces. We need the reminder. Your trek out west reminds me of recent hikes among those red rocks, yet one is rarely alone due to a crowded trail. Hikers are polite, understanding the need to pass by without falling off a cliff. RV’s on the road, not so much. Your piece also reminds me of another eloquent Pierre essay. Many years ago when opening The Gainesville Sun newspaper, I saw the picture of a lovely young man next to a superb story. Thank you for continuing to share your travels.

Pogo says

@Mr. Tristam

I’m getting all your site provides for so little—a poor pensioner’s annual $50.

Thank you.

Happy New Year.

FlaglerLive says

It matters more that you are among the Friends of FlaglerLive, no matter the amount, and you happen to contribute almost daily in many more ways at the site. Thank you Pogo.