After much public opposition that led to delays, debates and advocacy campaigns on all sides, the St. Johns Water River Water Management Board this afternoon voted to approve the wetlands-restoration project on the Intracoastal Waterway, opposite Gamble Rogers State Recreation Area in Flagler Beach.

The board unanimously approved a notice to proceed with a $516,000 project on some 100 acres of dragline ditches dug more than half a century ago as a failed mosquito-control project. The project will restore the acreage into wetlands over the next many years, adding shoreline protection against erosion and rising seas and, by the district’s projections, improving fishing and reducing invasive vegetation such as Brazilian peppers.

The decision ends months of wrangling between opponents of the project largely concentrated along its footprint and district officials. Opponents contend that the project is being rushed without the necessary data to back it up, that it will damage fishing grounds and hurt the existing ecology. The district cites past wetlands restorations’ evidence as proof that it helps the environment regenerate, above and below the water surface, and marsh science that makes such restorations necessary, if not vital, as counter-measures to rising seas and an already stressed coastline, where marshes are disappearing.

But there was a difference in the tenor of today’s opposition, compared with a meeting before the board in September–which paused the project–and a public meeting in Flagler Beach hosted by the district in early November. At both those previous meetings, the opposition was fierce with denunciations of the district’s approach and, in some cases, of its integrity, with opponents charged up enough to believe that they could possibly derail the project. Today’s opposition was more muted and resigned to the project’s reality, its voices often asking more for a few additional concessions than for a halt. Yet Flagler’s activism, not unusual for the county on various issues in recent years, had clearly taken the district by surprise, forcing it to recalibrate its approach and assumptions.

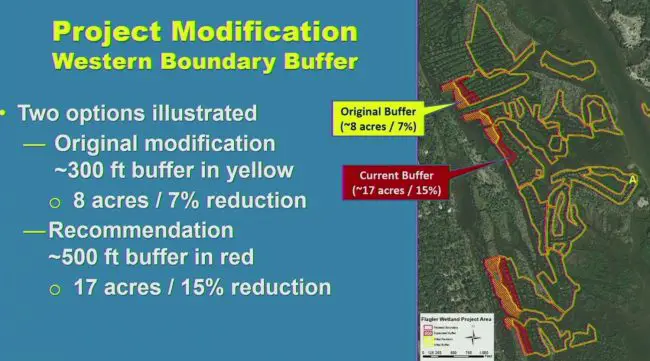

Today opponents’ most recurring request was for a doubling of the buffer between the project zone and its footprint, to 1,000 feet. In that, the requests failed: the boundary will be 500 feet, itself a substantial increase from what the district had initially proposed. The original buffer was about 8 acres, or 7 percent of the project area. The buffer was broadened to 17 acres, as Erich Marzolf, the district’s division of water and land resources, described it in a somewhat gauzy overview of the project at the beginning of the discussion.

The overview included a sharply produced video that summed up the project’s aims and summarized the controiversy it generated, all narrated by a soothing voice backed up by rippling-brook music.

Doug Bournique, a district board member and executive vice president of the Indian River Citrus League with a long record of protection of the Indian River Lagoon National Estuary Program, gave the most extended endorsement for the project. He said he’s been involved in almost every restoration project in two counties–St. Lucie and Indian River. “The best fishing I’ve been doing lately in the lagoon is at the mouth of these restored areas,” he said. There, he said he’d heard the same complaints–that restoration projects were disturbing fishing. “I have not known one project, not one, that has been a failure in what it set out to do, and I’ve been involved in almost all of them.”

The most eloquent voice for Flagler was not an unusual one: former Flagler County Commissioner Barbara Revels, a south Flagler resident and Flagler County native, who told board members she’d been in their shoes as an official responsible for listening to residents’ concerns (though she was elected, while district board members are merely appointed but still have taxing and spending authority). Revels proposed tying the project to improve water quality and narrow the project’s scope by planting oyster reefs and sea grasses instead, making it “a true marsh, not a mangrove forest that may or may not survive.”

Chris Farrell of Audubon Florida credited the district for restoring grounds to habitats more conducive to shorebirds. “We’re thinking long term for the health of our wildlife in Florida,” he said, before contrasting with Revels’s statement. “I’ve been in front of this board and a lot of agencies, talking about projects I wasn’t very happy with, and a lot of times I feel like I haven’t been listened to. This project was pretty amazing, the staffs from all the agencies involved, the meetings that were held, the maps out on tables, people there for you to respond to take feed-back.” He described it as a high bar the district set for future projects. “We’d love to have this level of response and interaction for projects we’re concerned about.”

Lnzc says

What a waste of money

Need streets fixed loads of other work