Another battle about using increases in local property taxes to bolster public schools will complicate upcoming state budget negotiations. And it’s not likely to make Flagler County school officials very happy.

In his $87.4 billion budget proposal for 2018-2019, Gov. Rick Scott on Tuesday called for a $770 million increase in funding for Florida’s kindergarten through 12th-grade education system. But nearly $7 out of every $10 of that increase would come from rising local property-tax revenue, much of it the result of increasing property values with a stronger economy.

Senate leaders support the governor’s plan, while House leaders remain firmly opposed to using the increased local property tax collections, arguing that such a move would represent a tax increase.

The projected $534 million increase in local property tax revenue includes $450 million in “required local effort” taxes and $84 million in discretionary local school taxes.

Required local effort has been a sore subject for Flagler County school officials, who are all for higher per-student funding, but not the way the current state formula sets the tax rate that establishes the Required Local Effort–meaning the tax revenue required from counties to fund the state education budget.

Local school boards have no say whatsoever in setting the local school tax that goes into the Local Required Effort. The rate is set by lawmakers. And each county’s tax rate differs, as does the proportion of revenue each must send to Tallahassee and the proportion of revenue that comes back. All that is based on an arcane formula called the District Cost Differential, a formula that hasn;t been changed in a decade.

The formula is costing Flagler County dearly.

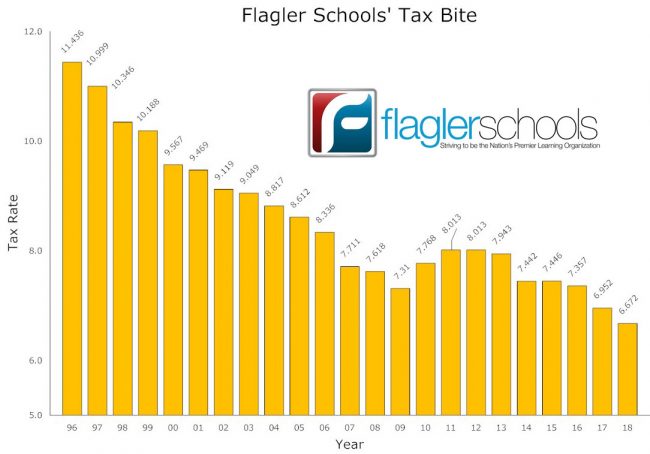

“We are the sixth-highest taxed district in the state for required local effort that’s set by the Legislature for our school taxes, and we receive back the 65th lowest dollars per student, OK?” says Tom Tant, the district’s finance director. “We pay higher taxes than Palm Beach for RLE, Orange County, Duval County, St. Johns County–you name it. Required Local Effort, that’s the biggest part of our taxes.”

In the past year, Flagler County dropped from 64th to 65th in the rankings of counties receiving state revenue per student. Flagler used to be 22nd, which wasn’t that good even then.

“And yet we are a high-B district,” Tant says. “But we’re getting starved to death. We can’t regulate the services we give to our kids. They’re required by law. They’re statute. And yet we’re getting so little funding per student.”

The average in the state is $7,200 in per-student funding. Flagler has never received $7,200 per student. The district is at $6,900 per student at the moment.

“We should have billboards out on this. It’s just incredibly unfair,” Tant said. “I don’t think our community knows. That’s the problem. Why are we paying the 6th highest taxes in required local effort and receiving the third-lowest funding per student in the state?” He’s given the presentation on the disparities to Rep. Paul Renner and Sen. Travis Hutson, the legislators who represent Flagler, four times in the past year.

Hutson said last month that he’s asked OPPAGA, the state Legislature’s Office of Program Policy Analysis and Government Accountability, to conduct a study about the cost differential. The study could spur reforms. But the study won’t be ready until after the coming legislative session, so the formula won’t be changed this year.

One of the most penalizing aspects of the cost differential is that counties that serve as bedroom communities are funded less than counties that draw jobs. “If you don’t work in Flagler County, it counts against us,” Trevor Tucker, chairman of the Flagler County School Board, said. “That’s some part of this ridiculous DCD, that’s probably the biggest portion that hurts us. The kids are here, it’s where the kids are that should make a difference.”

Scott’s budget proposal does not address the district cost differential or the disparities in required local effort. The proposal, in other words, could intensify the degree to which Flagler must pay taxes to the state while receiving less in return. The governor’s proposal further clouds the issue by redefining what a tax increase is, and is not.

In an explanation of Scott’s budget, his office noted the school proposal does not change the required local property-tax rate, meaning “there is not tax increase.”

“The amount of local funding provided in the (school funding formula) calculation primarily increased due to a 6.15 percent, or $117.1 billion, rise in the school taxable value that was the result of an increase in the value of Florida property,” the explanation said. “When property values rise, it’s a good thing for Florida families.”

Senate Appropriations Chairman Rob Bradley, R-Fleming Island, said the Senate supports Scott’s K-12 plan, including the use of increased local property tax collections.

“It’s not a tax increase. It’s just simply not,” Bradley said.

“If I were to buy a lawnmower at Home Depot for $200 in January and then buy the same lawnmower as a present for my brother four months later and it’s priced $230, there will be more taxes owed on the $230 purchase, but that’s not a tax increase,” Bradley said.

He said it’s “just the same tax rate being applied to a purchase that is a little higher than it used to be.”

But that explanation goes against Florida law’s definition of a tax increase. Even if property tax rates remain the same, if property tax revenue increases year-over-year, that’s considered a tax increase. For there not to be a taxd increase under that definition, the property tax rate must be set at the so-called rolled-back rate. Bradley’s explanation adds up to saying that a larger tax bite is not a tax increase.

But House Speaker Richard Corcoran, R-Land O’Lakes, reaffirmed Wednesday the House’s strong opposition to using increased property tax collections.

“I think our position has been very clear for the last two years and it will not change,” Corcoran said. “We’re not raising taxes.”

The House prevailed in the negotiations on the current 2017-2018 budget, with the Senate agreeing to roll back the “required local effort” property tax rate to offset the increase in tax collections.

Rather than having the majority of an increase for the K-12 system come from local property tax collections, lawmakers funded most of the $455 million increase from state revenue, along with a $92 million increase in discretionary local property-tax collections.

But that meant the Legislature had to shift $364 million in state revenue, which could have been used in other areas of the budget like health care or criminal justice, to come up with a $100 per-student increase in funding.

Under Scott’s new plan, per-student funding would rise by $200, but that is based on $450 million in property taxes. If lawmakers reject using the property tax revenue, they will have to again shift more state revenue into the schools’ budget, which will be even more difficult in the coming year.

“We’re very committed in the Senate to K-12 education,” Bradley said. “And an important part of that commitment is making sure that we have the (local property tax collections). It’s not a tax increase. I agree with the governor. And that’s where we are.”

Corcoran downplayed the differences with the Senate over the next state budget, which will be debated when lawmakers begin their annual session in January.

“Where we are right now is in a good place and the likelihood we’re going to end in a good place is as strong as ever,” he said. “I think it’s a good situation.”

–FlaglerLive and the News Service of Florida

Mark says

Bring it on. Education is important. Get back to reading, writing and arithmatic! Leave the life lessons to the parents!

Born and Raised Here says

Our Students deserve the best education money can buy. I say raise the education tax for a good cause.