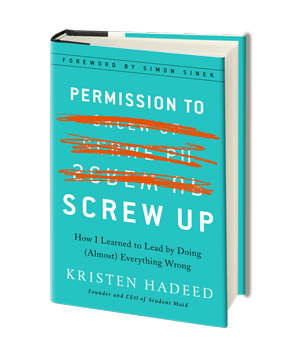

Kristen Hadeed, who grew up in Palm Coast and graduated from Flagler Palm Coast High School in 2006, was interviewed this morning by Megyn Kelly, host of NBC’s Megyn Kelly Today, part of Hadeed’s promotion of her first book: “Permission To Screw Up: How I Learned To Lead by Doing (Almost) Everything Wrong” (Penguin).

The book traces Hadeed’s evolution from an amateur leader of her cleaning company, Gainesville-based Student Maid, which she started halfway through her undergraduate years at the University of Florida in Gainesville, through the company’s decade’s growth, which paralleled her own as a now-accomplished and highly-sought speaker on the leadership circuit.

The segment with Kelly was barely five minutes long. “It was scary,” Hadeed said in a text afterward, though it was Kelly who was not entirely prepared for the interview, repeatedly focusing on her own assumptions about millennials, and focusing almost exclusively on millennial stereotypes–which Hadeed takes pain to debunk in her book–rather than on the book’s more revealing insights.

“You’ve heard it, they’re all raised by helicopter parents who don’t allow their little cupcakes to fail,” Kelly said, opening the segment with one of her repeated uses of the word “cupcakes” (which never appears in Hadeed’s book), though she conceded that Hadeed and another author she appeared with, Rachel Simmons, author of “Enough As She Is,” themselves are living examples that belie the stereotype.

Kelly, at any rate, had read the press release advancing Hadeed’s book and asked her about what launched her into the cleaning business. “I was a student at the University of Florida,” Hadeed said, “I thought I wanted to be an investment banker, and one day I walk into the mall, saw these jeans, had to have them, knew my parents would never ever, in any universe, give me the money to buy them”–her father, Al Hadeed, is the Flagler County Attorney–“and so I put an ad on Craig’s List to clean a house, thinking that would be an easy way to make the money, and I did a terrible job. But miraculously the woman hired me back every week, and that’s how it started. That was 10 years ago.”

Kelly, at any rate, had read the press release advancing Hadeed’s book and asked her about what launched her into the cleaning business. “I was a student at the University of Florida,” Hadeed said, “I thought I wanted to be an investment banker, and one day I walk into the mall, saw these jeans, had to have them, knew my parents would never ever, in any universe, give me the money to buy them”–her father, Al Hadeed, is the Flagler County Attorney–“and so I put an ad on Craig’s List to clean a house, thinking that would be an easy way to make the money, and I did a terrible job. But miraculously the woman hired me back every week, and that’s how it started. That was 10 years ago.”

“So now you run your own business, you only hire millennials,” Kelly said (not actually true: Hadeed mostly hires students and, aside from realizing that “my hiring requirements were BS,” makes a point of noting that students these days cut across all ages, and that her challenges had little to do with the students’ age so much as their status and schedules as students). Kelly then referred to the time when Hadeed lost most of her workforce when 45 employees walked out on her as she was enjoying a salad with her feet up.

“That moment was really defining for me,” Hadeed said. She was 21 at the time. “I had no idea what leadership was, I was sitting in this air-conditioned clubhouse while my employees were cleaning filthy apartment, and I thought that was leadership.” But she managed to get the 45 back–she actually invited them to her place and turned them around with pizza and apologies and her first venture into exposing her vulnerabilities rather than presuming to know better than they did, a strategy that would turn out to be key to her subsequent successes.

“We have parents who want to be a part of the interview,” Hadeed said in her chat with Kelly, eliciting laughter from the audience.

“Or, you know, how can you say that my son or daughter needs to be a better duster, and I’m like, well?”

“OMG,” Kelly said. “Are you serious?”

“We both have the same goal, we want the child to be successful,” Hadeed said, explaining that it’s just a matter of letting the students having room to figure it out. She could not on the air reflect the irony of the word “child,” as she used it with Kelly, though she reflects it archly in the book when she notes the “rare occasions I even got emails from their parents— those same overhelping moms and dads— who wanted to know why I’d dared to criticize their twenty-year-old ‘child’s’ dusting techniques. (Oy vey.)”

Kelly missed the part about the rarity of those contacts from parents, preferring again to focus on the the exception. “Who are these parents who interfere with their children’s every move,” she insisted. The occasional and disappearing Dick Cavetts aside, television hosts are not paid, of course, for their book-reading skills, as authors invariably discover in their few minutes on set.

The segment appears below.

![]()

Wishful thinking says

Another Hadeed succeeds!

Wonderful family indeed