By Corinne Schwarz

The idea that sex trafficking is an urgent social problem is woven into American media stories, from reports of Republican U.S. Rep. Matt Gaetz’s

alleged trafficking of teenage girls to debunked QAnon conspiracy theories about a sexual slavery ring run through online retailer Wayfair.

The common perception of sex trafficking involves a young, passive woman captured by an aggressive trafficker. The woman is hidden and waiting to be rescued by law enforcement. She is probably white, because, as the legal scholar Jayashri Srikantiah writes, the “iconic victim” of trafficking usually is depicted this way.

This is essentially the plot of the “Taken” movies, in which teenage Americans are kidnapped abroad and sold into sexual slavery. Such concerns fuel viral posts and TikTok videos about alleged but unproven trafficking in IKEA parking lots, malls and pizza shops.

This is not how sex trafficking usually occurs.

Since 2013, I have researched human trafficking in the midwestern U.S. In interviews with law enforcement, medical providers, case managers, victim advocates and immigration lawyers, I found that even these frontline workers inconsistently define and apply the label “trafficking victim” – especially when it comes to sex trafficking. That makes it harder for these professionals to get trafficked people the help they request.

So here are the facts and the law.

What is sex trafficking?

The Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act of 2000 provides the official legal definition for sex and labor trafficking in the United States.

It makes “trafficking in which a commercial sex act is induced by force, fraud, or coercion, or in which the person induced to perform such act has not attained 18 years of age” a federal crime.

In short, to legally qualify as sex trafficking, a sex act involving an adult must include “force, fraud, and coercion.” This could look like someone – a family member, a romantic partner or a market facilitator colloquially described as a “pimp” or “madam” – physically abusing or threatening another adult into sex for money or resources.

With minors, any and all sexual exchanges – that is, trading sex for something of value like cash or food – are considered sex trafficking.

How common is sex trafficking?

Data on human trafficking is notoriously messy and difficult to measure. Survivors may be hesitant to disclose their exploitation out of fear of deportation, if they are undocumented, or arrest. That leads to underreporting.

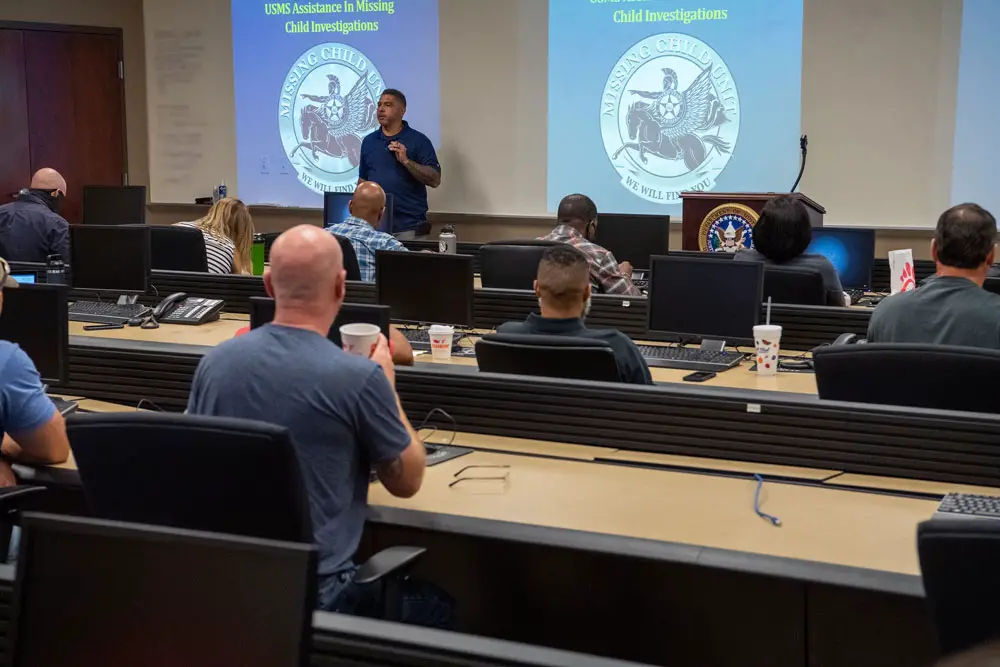

![]() One way to approximate how many people are being trafficked in the United States is to consult federal grant reports, as suggested by anti-trafficking nonprofit Freedom Network USA.

One way to approximate how many people are being trafficked in the United States is to consult federal grant reports, as suggested by anti-trafficking nonprofit Freedom Network USA.

For example, the federal Office for Victims of Crime served 9,854 total clients – some of whom identified as trafficked, others who showed “strong indicators of trafficking victimization” – between July 2019 and June 2020. The Department of Health and Human Services Office on Trafficking in Persons served 2,398 trafficking survivors during the 2019 fiscal year.

Data from the same office also shows that 25,597 “potential victims” of sex and labor trafficking were identified through calls to the National Human Trafficking Hotline.

Again, this data is incomplete – if survivors have not accessed these particular resources or called these specific hotlines, they are not represented here.

What does sex trafficking look like?

As with other sexual crimes, like rape, sex trafficking survivors often experience violence at the hands of someone they know, not a complete stranger.

A study from Covenant House New York, a nonprofit focused on homeless youth, found that 36% of the 22 trafficking survivors in their survey were trafficked by an immediate family member, like a parent. Only four reported “being kidnapped and held against his or her will.”

Often, trafficking victims are younger transgender people or teens experiencing homelessness who exchange sex with others to meet their basic needs: shelter, economic stability, food and health care. Trafficking frequently looks like vulnerable people struggling to survive in a violent, exploitative world.

“They are creating sexual solutions to nonsexual problems,” says San Francisco-based researcher Alexandra Lutnick.

Under U.S. law, these youth are trafficking victims, because of their age. But they may reject the label, preferring terms like “survival sex work” or “prostitution” to describe their experiences.

Trafficking victims engaged in survival sex may well be arrested rather than offered help like housing or health care. If they cannot prove “force, fraud, or coercion,” or if they refuse to comply in a criminal investigation, they risk shifting from victim to criminal in the eyes of law enforcement. That can mean prostitution charges, felony offenses or deportation.

Such punishments are most commonly used against Black, Indigenous, queer, trans and undocumented sex-trafficking survivors. Black youth are disproportionately arrested for prostitution offenses, for example, even though legally any underage commercial sex is sex trafficking.

What is the difference between sex work and sex trafficking?

Legally and in other meaningful ways, sex work and sex trafficking are different.

Sex work is consenting adults engaging in transactional sex. In almost all U.S. states, it is a criminal offense, punishable with fines and even jail sentences.

Sex trafficking is nonconsensual, and it is generally treated as a more severe crime.

Most sex workers’ groups acknowledge that sex work is not inherently sex trafficking but that sex workers can face force, fraud and coercion because they work in a criminalized, stigmatized profession. Sex workers whose experiences meet the legal standards of trafficking may nonetheless fear disclosing that to police and risking arrest for prostitution.

Conversely, sex workers can be mistakenly labeled by police and advocates as “trafficked” and find themselves in the custody of law enforcement or social service agencies.

What can be done?

Based on my research, reducing sex trafficking requires changes that might prevent it from occurring in the first place. That means rebuilding a stronger, supportive U.S. social safety net to buffer against poverty and housing insecurity.

[Over 100,000 readers rely on The Conversation’s newsletter to understand the world. Sign up today.]

In the meantime, trafficking victims would benefit from efforts by frontline workers to combat the racism, sexism and transphobia that stigmatizes and criminalizes victims who don’t look as people expect – and are struggling to survive.

![]()

Corinne Schwarz is Assistant Professor of Gender, Women’s, and Sexuality Studies at Oklahoma State University. This work was supported by the National Science Foundation under grant 1624317. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

![]()

![]()

Mark says

What is the penalty for promoting human trafficking?

Pogo says

@You’re welcome

https://www.google.com/search?d&q=What+is+the+penalty+for+promoting+human+trafficking