By Christopher Ewing

On Feb. 23, 2024, Daqua Lameek Ritter was found guilty of a hate crime for the murder of Dime Doe, a transgender woman from South Carolina believed to be in a relationship with Ritter.

The ruling marks both the first trial and first conviction of a hate crime on the basis of gender identity under the 2009 Matthew Shepard and James Byrd Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act.

Under the act, hate crimes are “violent acts motivated by actual or perceived race, color, religion, national origin, gender, sexual orientation, gender identity or disability of a victim.”

Between 2013, the year the FBI first began monitoring hate crimes motivated by gender identity, and 2022, the bureau recorded 1,969 hate crimes against trans and gender-nonconforming people, including a rise in 2022.

Ritter’s trial reflects low rates of prosecution for all hate crimes. Between 2005 and 2019, federal prosecutors investigated 1,878 suspects in hate crime matters, resulting in 310 prosecutions and 284 convictions for hate crime statutes violations.

I am a historian who studies the development of hate crime activism in Australia, Europe and the U.S. My research has found that hate crime legislation is strikingly ineffective at preventing violence through producing convictions, as is clear from the fact that it took 15 years to produce a conviction based on gender identity under federal law.

The legislation was hailed at the time by leading gay rights advocate Joe Solmonese as “our nation’s first major piece of civil rights legislation” for LGBTQ people. But it was not the result, as many believe, of unequivocally progressive impulses. Instead, it emerged from an unexpected convergence of gay and civil rights goals and a Reagan-era war on crime.

Saul Loeb/AFP/Getty Images

Hate crime statistics

Through the 20th century, same-sex-desiring and gender-nonconforming people were often subject to violence and police harassment. Although early grassroots anti-violence initiatives in the 1970s offered some protection, LGBTQ people had little legal recourse.

By 1980, 29 states still had anti-sodomy statutes on the books, and LGBTQ activists faced a backlash against limited gains of the 1970s. The 1980 election of Ronald Reagan, supported by an ascendant religious right, embedded this backlash in national politics. It also led to two important consequences for LGBTQ politics.

First, the medical reporting of what would become known as AIDS in 1981 among several gay men established a lasting association between homosexuality and deadly disease, triggering further resurgence of homophobia.

Second, anxieties about a national crime wave led many to support the Reagan administration’s tough-on-crime approach, including expanded policing and harsher sentencing.

The claims of a national crime wave were based on data collected from the FBI’s Uniform Crime Report. Begun in 1930, the program gathered data submitted voluntarily by local and state law enforcement agencies.

However, discrepancies between regional jurisdictions, inability to track crime unreported to the police and inefficient data-collection procedures, among other factors, led to questions about whether the system accurately represented national trends.

More detailed system

At the start of the 1980s, the FBI and several other law enforcement agencies began modernizing the Uniform Crime Reporting Program. The agencies’ joint efforts through the decade resulted in an FBI-managed system in 1989 that moved from summary reporting to more detailed, incident-based reporting.

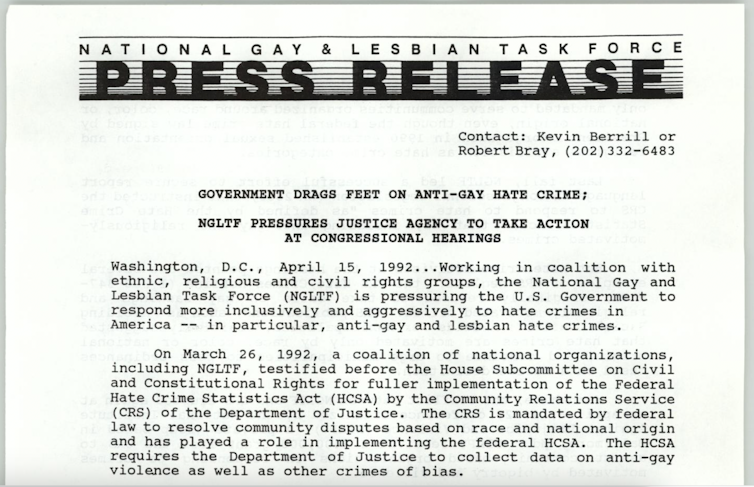

In 1986, at the height of the AIDS crisis and amid national anxieties about violent crime, gay activists Kevin Berrill of the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, the country’s largest gay rights group at the time, and Diana Christensen, of San Francisco’s Community United Against Violence, testified before Congress on anti-gay violence. Together they argued that such violence constituted a “second epidemic” after AIDS. Active data collection was essential to addressing violence. Legislation on hate crime statistics collection then under consideration excluded attention to sexual orientation, requiring revision before passing Congress.

Statistics alone were not enough. According to Berrill and Christensen, approximately 80% of anti-gay attacks went unreported to the police, and those that were reported were often dismissed. The activists recommended “tougher laws” that would allow federal prosecution if local authorities failed to do so. Berrill’s organization further “commends the Reagan administration” for its concern with victims of violent crime, and called on “federal, state and local agencies concerned with crime and its victims” to study and prevent anti-gay violence.

These arguments were successful. Aided by additional civil rights organizations, the Hate Crime Statistics Act passed Congress with sweeping support and was signed into law by Reagan’s successor, President George H. W. Bush, in 1990. The law defined “hate crimes” as “crimes that manifest evidence of prejudice based on race, religion, sexual orientation, or ethnicity” and authorized the attorney general to begin collecting data on such crimes.

The Hate Crime Statistics Act was the first update to the revised Uniform Crime Reporting Program, adding prejudice as a motivation. While doing so informed prevention efforts, it also made hate-motivated violence a federal criminal category.

And that laid the groundwork for future tough-on-crime legislation.

University of North Texas Libraries

Expanded hate crime laws

The new law provided funding only for the collection of statistics, not policing and prosecution of crime.

Law enforcement agencies were asked to provide data on a voluntary basis. That meant data might not be provided, given the documented problem of anti-gay police bias. Activists in some cities, including San Francisco, New York and Dallas, were able to collaborate with individual police officers on violence prevention initiatives. But efforts nationally were piecemeal at best, hampered by Republican opposition.

In 1993, however, the Hate Crimes Sentencing Act, which established federal sentencing guidelines for hate crimes, was added to the bipartisan Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act that was pending in Congress. That legislation, passed in 1994, increased funding for police forces, law enforcement agencies and correctional facilities. It has been criticized for expanding U.S. prison systems and promoting punitive responses to crime.

With the Hate Crimes Sentencing Act attached to what was the largest crime bill in U.S. history, it became emblematic of a bipartisan tough-on-crime era.

Prosecuting hate crimes

In 1998, the highly publicized murders of Matthew Shepard, a gay college student in Wyoming, and James Byrd Jr., a Black resident of Jasper, Texas, launched renewed pressure to expand federal authority to prosecute hate crimes, rather than simply gather data or establish sentencing guidelines.

In 2001, the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act was introduced in Congress. Republican and conservative opposition meant the act was not passed until 2009. It expanded federal jurisdiction over hate crimes and allocated local police forces and courts additional money to investigate and prosecute hate crimes.

The law included gender identity as a protected category, making it theoretically applicable to crimes against any LGBTQ+ person. It was under this law that Ritter was convicted of the murder of Dime Doe, a transgender woman.

The law is ineffective at both accumulating data and enforcing penalties. Not only was the first federal conviction for a hate crime on the basis of gender identity made 15 years after the law’s passage, but hate crimes generally are also subject to chronic underreporting.

In 2022, the FBI reported 11,634 offenses categorized as hate crimes. While the FBI explains that the Uniform Crime Report is not exhaustive, some researchers have indicated that the system specifically underreports hate crime data. In 2022, about 80% of participating agencies reported zero hate crimes, which diverges from other reputable data sources.

In short, and as researchers continue to point out, the expansion of national criminal law since 1990 has yet to prove effective at preventing hate crimes and other violence.

Christopher Ewing, Assistant Professor of History, Purdue University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

![]()

Christopher Ewing is Assistant Professor of History at Purdue University.

dave says

‘federal hate-crime law ‘, hateful people/bad people/criminals don’t care about laws. Its that simple.

Skibum says

Since the 2001 federal hate crime law was enacted, there have been numerous instances where that law could have, and should have been applied but was not. I think the problem has been with some local law enforcement and prosecutors who are either 1) reluctant to make a public proclamation that they have a “hate crime problem” in their jurisdiction, or 2) reluctant to cede control and authority over criminal cases to federal prosecutors when they could instead score points with local citizens by retaining local control of these criminal cases, or 3) the local authorities ignore an obvious hate motivation and decide to prosecute instead using other charges, or lastly 3) the hate crime cases involve victims who are LGBTQ and other marginalized citizens who are not afforded the same protections and valued as much in their local communities as others. Either way, both law enforcement agencies as well as local prosecutors need to do better to actually recognize and take action when a crime is committed by someone purely because of hatred, so they can bring justice to victims of hate crimes.