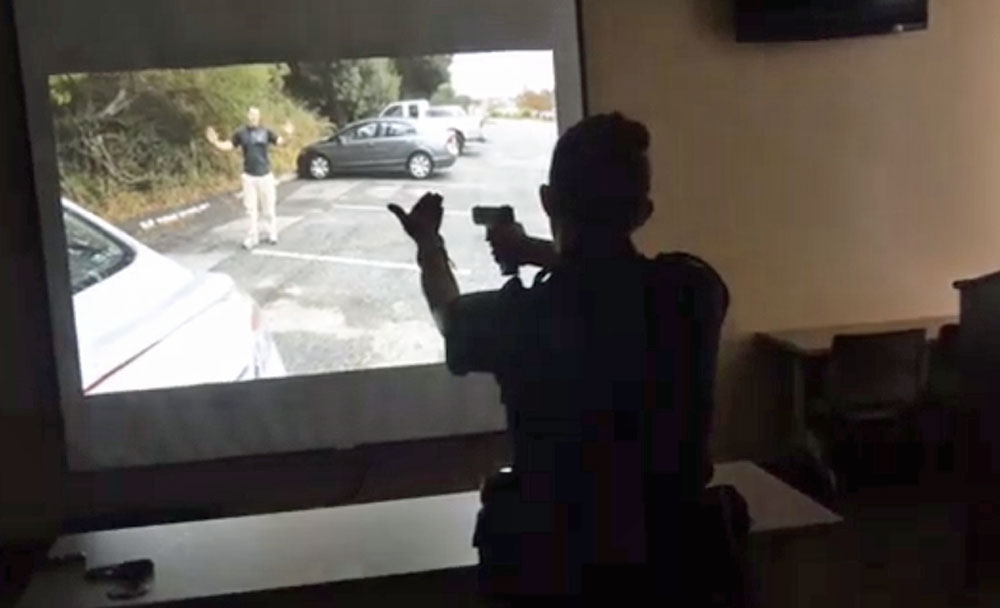

Kathryn Gordon is a 21-year-old native of Flagler, a graduate of Flagler Palm Coast High School and a Flagler County Sheriff’s deputy, on the job 10 months. She’s been patrolling on her own just four months. On Tuesday, she faced a series of simulated situations designed to place a deputy in the thick of realistic encounters with members of the public, some of them routine, some of them not so routine, and dangerous.

It was part of a three-week training segment that will put every one of the agency’s 235 deputies, including corrections deputies, through simulated, unpredictable and at times violent situations to test their split-second judgments and evaluate their skills either at de-escalating tense situations or using the proper level of force when necessary.

In one case, a scenario has deputy Gordon responding to the report of a suspicious person in a parking lot behind a business. As the camera angle simulates the deputy approaching the man, the man is pacing back and forth, muttering to himself. Gordon hears and sees him clearly. “Sir, let me see your hands,” the deputy tells him, gun drawn. The man turns around, looking at the ground, unresponsive to the deputy. He holds a knife in his right hand. “Put down the knife,” the deputy tells him. He mumbles something about having “too many problems.”

“What kind of problems, what’s going on?” the deputy asks in a clear, assertive but non-threatening voice. “Talk to me, what’s going on, sir?”

Deputy Gordon Faces an Armed Man in Crisis:

‘Nobody understands me, I need to get this done right now,” the man replies. “What do you guys want?” But after hearing the deputy’s even-voiced demands that he put down the knife, he complies and backs up toward her.

Gordon conducted the encounter well. The second scenario seems less difficult. It’s a traffic stop. Gordon approaches the driver’s side of a minivan. Inside, a 30-something man is holding the wheel, his fingers fidgeting as Gordon tells him he drove through a stop sign. He hands her his papers and holds on to the steering wheel. The deputy goes back to her patrol car, but as she walks back toward the van, the man opens the door and leans out–”Sir, stay in the vehicle,” the deputy yells out. Too late. The man is armed and firing at Gordon, who ducks right, pulls out her gun and fires at him, apparently hitting him. He slumps back into the van. “Let me see your hands,” she yells out. The scenario ends.

“That was a great job,” Sheriff Rick Staly, who had been standing behind Gordon, tells her. “Let me just point something out to the media that maybe they wouldn’t pick up on because they haven’t had your training. But as soon as he came out with a gun and she identified him, she moved from where she was and made herself a smaller target, pulling her gun, and that’s exactly what you teach.”

This week and the next two, the Flagler County Sheriff’s Office got possession of the simulator from the Florida Sheriffs’ Association, at no cost to the agency. The simulator is a $50,000 piece of machinery that includes a computer, video, weapons that are nearly identical to those worn by deputies and electronically linked to the scenarios, and innumerable such scenarios that can be tailored for different responses. The system–The MILO Range Mobile-Situational Awareness Training System–is run by Sgt. Ryan Emery, who’s in charge of training at the agency and who’s leading every training session for the deputies.

The real-life scenarios are the sort deputies “are likely going to encounter at some point in their career,” Staly said. “It just reinforces the training that they’ve had and it puts them in a position to make those split-second decisions, and if there’s something that they can improve on, your instructor can critique it, educate them, put them back through the scenario again, and in this case if they make a mistake in that split-second decision, no one is getting hurt. You make a mistake in real life, in a split second, it could have deadly consequences. So you want to put them under pressure, you want to put them as realistic as you can.”

Staly spoke of his own experience, getting shot three times in 1978 when he and another deputy from the Orange County Sheriff’s Office were chasing a suspect. The first deputy went up to him and began arresting him for disorderly conduct. There was a brief foot chase, the deputy tackled him, the suspect managed to grab the deputy’s gun. Staly reached for his gun, kicked the man in the chest, and was shot twice in the arm and once in the chest, a round that was stopped by his flack vest. The man then exchanged gunfire with the other deputy before he was shot five times, but survived. He was on “purple haze,” Staly said. “He didn’t complain about the bullet holes, he complained about where I kicked him in the chest.” He was sentenced to 20 years, served eight and was released, only to be rearrested.

“What kind of problems, what’s going on?” the deputy asks in a clear, assertive but non-threatening voice. “Talk to me, what’s going on, sir?”

A Traffic Stop Turns Violent:

The whole incident unfolded in 11 seconds.

“This isn’t about me, but I just want to tell you how quick these things can change,” Staly said. When an officer makes the decision to arrest, “the suspect has three choices that you can’t make for them. You might be able to help them make that decision by the way you present yourself. But they’re going to make one of three choices. They’re going to submit and allow you to arrest them without incident. They’re going to flee. Or they’re going to fight. And his choice was initially to flee, and then to fight.”

In Flagler, the sheriff said, there’s no much aggression toward law enforcement to speak of.

“We have a great community here that supports its law enforcement and I’ve got a great team, they’ve all trained, from de-escalation to self-defense tactics, and our use of force in this agency since I’ve been sheriff are down 46 percent?” he said. “We do get people that are aggressive towards us but if they’re having a mental health issue or something else going on. It’s not necessarily because we’re wearing a uniform, like you’ve seen around the country.”

The agency is in its ninth year of avoiding an officer-involved shooting that resulted in a fatality. The first time deputies shot an individual in those nine years took place earlier this year in West Flagler. The man was, who’d previously been in a situation that approximated an attempted suicide-by-cop, shot in his car as he was reaching for a gun. He survived.

With the simulator, scenarios have alternate endings, so depending on how the trainer observes the deputy handling the situation, the simulator will be directed to respond accordingly. If the deputy is not doing a good job of de-escalation, the simulator can be directed to go into an assault or more violent scenario. But the simulator can’t be specifically programmed, say, to measure a deputy’s response to a white assailant as opposed to an assailant of color. It’s not programmed to detect cognitive bias, for example.

“The scenarios are what they are as far as who the actors are,” Emery said. “It’s not like a video game where we can design who the characters are or anything like that. It’s actually real video footage. So when they design it, they just use video based off who the actors are. There are so many options that we can select, like location and things like that, but it’s whatever the company has provided.”

Still, the training is designed to detect potential issues and allow deputies to work on them with constructive critiques. “We want to make sure we design it to where all the scenarios don’t end in a shooting scenario, and all the scenarios don’t end in compliance,” Emery said. “We want to make sure there’s a variety. And we want to make sure they don’t leave on a bad note. So if someone struggles, obviously we’ll continue to train with them, and I’ll actually notate if it’s something egregious, then obviously we’ll address it that way and they’ll continue to train until they meet our expectations.”

For example, if a deputy isn’t using good verbal commands, or if the deputy doesn’t act the way he or she needs to act with tact and courtesy as encounters are initiated, or don’t engage a suspect with the appropriate level of force should it become necessary. “We will discuss it, and that’s what’s good about this, we can discuss it immediately after,” Emery said, and “replay step by step: this is what the subject did, this is what your reactions were, and we can play the scenario over again.” Emery likes to add a variable to the scenario, changing the ending slightly so the deputy still won’t know what’s coming. “As long as we see the progress and we make sure that they’re meeting our expectations and what the agency’s vision is on use of force and de-escalation, then they’re good.”

Deputies are run through four to five scenarios. Some of them have had to go through more scenarios if they show a need. Some deputies with experience might need less. New hires will get an entire week–40 hours–of crisis-intervention training, an entire week of live scenarios, and on top of that, the simulator, as long as the agency has it. “Between all of them, we’re able to hit all the different topics we want to cover,” Emery said. (The department can request the simulator again in the future.)

“We try to build them up and we try to make sure that they learn from their mistakes,” Emery said. “We try not to set people up for failure, but we do challenge them. When you challenge somebody enough, eventually people may make a mistake when it comes to verbal commands, or they may identify a weapon not as fast as we’d like them to do it, so we continue to build them up, and in the end it usually builds their confidence up.”

Patrice says

So happy to see Fcso being proactive. Today our media plays monday morning quarterback when reporting and until you are faced with sutuations that require split second decisions that can be fatal they should not be blaming LEO. It sounds like this simulator will lower the margin of error. Great job FCSO!

Concerned Citizen says

Well put.

Between the Airforce and then going to work for our local SO after coming home I spent a total of 10 years in Law Enforcement. Then made the move to Fire Rescue and retired.

The training our first responders have is first rate. And technology gives them that edge. Are they perfect? No. They are human beings just like us. But training helps build that confidence and professionalism. It boils down to individual ethics as to whether or not you uphold your oath.

I have seen the changes over the years and marvel at them. I can remember standing on the side of the road running a DL check over the radio. And sometimes having to wait for it to come back while writing a ticket. Sometimes a bad guy got away because you had to wait for the check to come back when you had only stopped him for speeding. And let him go on to answer a priority call. Now our LEO’s have laptops and license plate readers. And the results are instant. Many folks cry invasion of privacy but it ads a layer of safety that we didn’t have in the mid 90’s. And I’m ok with that.

All in all we are fortunate to have a Sheriff who tries to take care of his agency. And uses the tools at his disposal to do so.