By Aggie Yellow Horse

The census conducted in the U.S. every 10 years is meant to count everyone. But it doesn’t actually count everyone.

After every census, the U.S. Census Bureau reports how well it did at counting every person in the country. In 2020, as in past years, the census didn’t get a completely accurate count, according to the bureau’s own reporting. The official census number reported more non-Hispanic whites and people of Asian backgrounds in the U.S. than there actually were. And it reported too few Blacks, Hispanics and Native Americans who live on reservations.

The Conversation U.S. asked Aggie Yellow Horse, a sociologist and demographer at Arizona State University, to explain why, and how, the census misses people, and how it’s possible to assess who wasn’t counted._

AP Photo/Matthew Brown

1. Who gets missed in the census?

The people most commonly missed are those with low income, people who rent or don’t have homes at all, people who live in rural areas and people who don’t speak or read English well. Often, these are people of color – Black Americans; Indigenous peoples; or people of Hispanic, Asian or Pacific Islander backgrounds.

Because of their living situations, these people can be hard for census takers to track down in the first place. And they may be more reluctant to participate because of concerns about confidentiality, fear of repercussions and distrust of government.

Nevertheless, the U.S. Census Bureau tries to count everyone, aiming targeted public relations campaigns at specific communities to encourage members to participate. In addition, Census Bureau employees knock on doors in person across the country, trying to follow up with those who did not respond to mailings, announcements and events.

However, the pandemic made that process more difficult for the 2020 census, both by making people uncomfortable with in-person visits and by shortening the timeline for collecting the data.

2. Who got missed?

The official estimates show that the 2020 census was really very accurate, capturing 99.8% of the nation’s residents overall. But the census missed counting 3.3% of Black Americans, 5.6% of American Indians or Alaskan Natives who live on reservations and 5% of people of Hispanic or Latino origin. This could mean missing about 1.4 million Black Americans; 49,000 American Indians or Alaskan Natives who live on reservations; and 3.3 million people of Hispanic or Latino origin.

This performance is much worse than in the previous two censuses, when smaller proportions of those populations were missed.

The 2020 census also counted 1.64% more non-Hispanic whites than there actually are in the country. For example, college students could have been counted twice – at their college residence and at their parents’ home.

3. How can they count the people who were missed?

It can be puzzling to understand how the Census Bureau can know how many people it missed. Efforts for measuring census accuracy started in 1940. Census officials use two methods.

First, the Census Bureau uses demographic analysis to create an estimate of the population. That means the bureau calculates how many people might be added to the population counts, through birth registrations and immigration records, and how many people might be removed from them, through death record or emigration reports. Comparing that estimate with the actual count can reveal an overall scale of how many people the census missed.

As a second measure, the Census Bureau runs what it calls a “post-enumeration survey,” taken after the initial census data is collected. The survey is conducted independent of the census and randomly sent to a small group of households from census blocks in each state, the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico. The results of that survey are compared with the census results for those households and can reveal how many people were missed, or if some people were counted twice or counted in the wrong place.

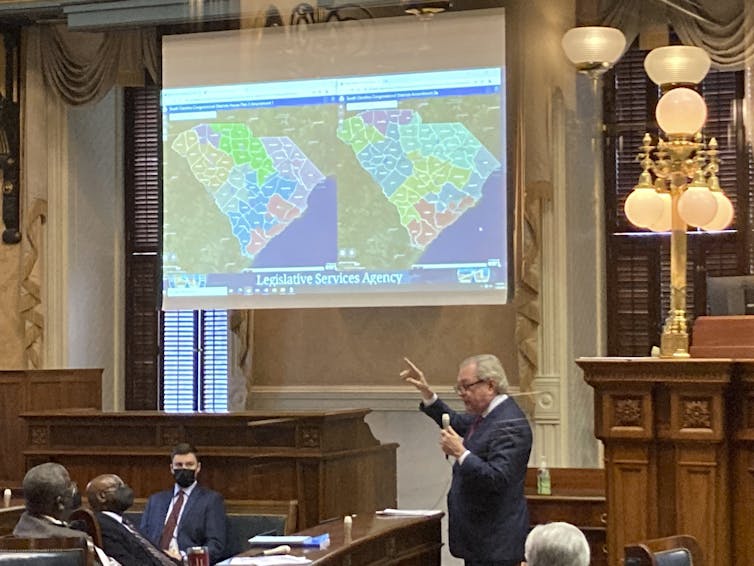

AP Photo/Jeffrey Collins

4. Can the Census Bureau fix its data?

The Census Bureau has determined that its 2020 data is not accurate and has measured the amount of that inaccuracy. But in 1999, the Supreme Court ruled that the bureau cannot adjust the numbers it sent to Congress and the states for the purpose of allocating seats in the U.S. House of Representatives and, therefore, Electoral College votes. That’s because federal law bars the use of statistical sampling in apportionment decisions and requires those changes to be made only on the basis of how many people were actually counted. That means political representation in Congress may not accurately reflect the constituencies the representatives serve.

But the numbers can be adjusted when used to divide up federal funding for essential services in communities around the nation. More than US$675 billion a year is provided to tribal, state and local governments proportionally according to their population numbers.

However, that adjustment happens only if tribal, state or local officials ask for it. The Census Bureau’s Count Question Resolution program can correct 2020 census data until June 2023. After the 2010 census, the program received requests from 1,180 governments, of out about 39,000 nationwide. As a result, about 2,700 people were newly added to the census count, and about 48,000 household addresses were corrected.

This approach can lessen the harm done to communities where the census count missed people. But it doesn’t prevent the Census Bureau from missing them – or others – in the next census.

![]()

Aggie Yellow Horse is Assistant Professor of Asian Pacific American Studies at Arizona State University.

mindurownbusiness says

How convenient…

Mark says

Interesting. But, nothing is perfect especially when touched by humans.

Jimbo99 says

They mailed a census to every address, you could also take the census on-line. That means if you had a smartphone or a tablet you could have counted yourself & entire family at your home address without anyone coming to your door or mailbox. I’d be more concerned that those living in homeless camps in a wooded area or under a train bridge weren’t counted vs being on an Indian Reservation. They were more concerned about asking for the status of your ownership, like whether you rented or owned & whether you carried a mortgage or not. See the Fed is raising interest rates, after the 1st waves of 2021 to entice those in financial hardship to sell their cars & houses for cash. The banking & lending industry is seeking to refinance homes at higher fixed interest rates. The census in that regard became a tool to manage the real estate inventory from the pandemic. All one had to do is indicate themselves and social security for anyone at the address they claim to be living at.

DaleL says

Flagler Live uses a capitalization style which intentionally does not capitalize “white” when referring to race, but does capitalize “Black”. The rational is that “White” (capitalized) is associated with white supremacy groups and white power groups. On the US Census form “White” is capitalized. I am not a supporter of white supremacy or white power. As such, I do not want to be associated with them. My skin is also not the color white. I have read that some people find Caucasian to be offensive. I don’t want to offend people, so I do not usually call myself a Caucasian. European American would work, but it is a mouthful and not what is listed as “race”.

As result, I marked “Some other race”. Which leads to a question, the Census is largely self reporting. How many other people choose to answer other than expected?

The Geode says

I am black. My neighbors are black. None of us bothered with the census. In fact, we were laughing about it as I was tossing mine in the recycle bin. Maybe THAT is the problem and not some “over-reaching conspiracy” or the “racism” y’all like to conjure up and blame for everything…

Whathehck? says

Why didn’t you and your neighbors bother to return the census?

Don’t you care about funds in your area or have political representation?

The Geode says

Actually. No. No matter WHO my “political representative” is, MY life doesn’t seem to change and what are these “funds” you speak of? Whatever those “funds” are (or not), that doesn’t seem to change things, either.

Countonme says

If you know how many you counted and how many you didn’t count…