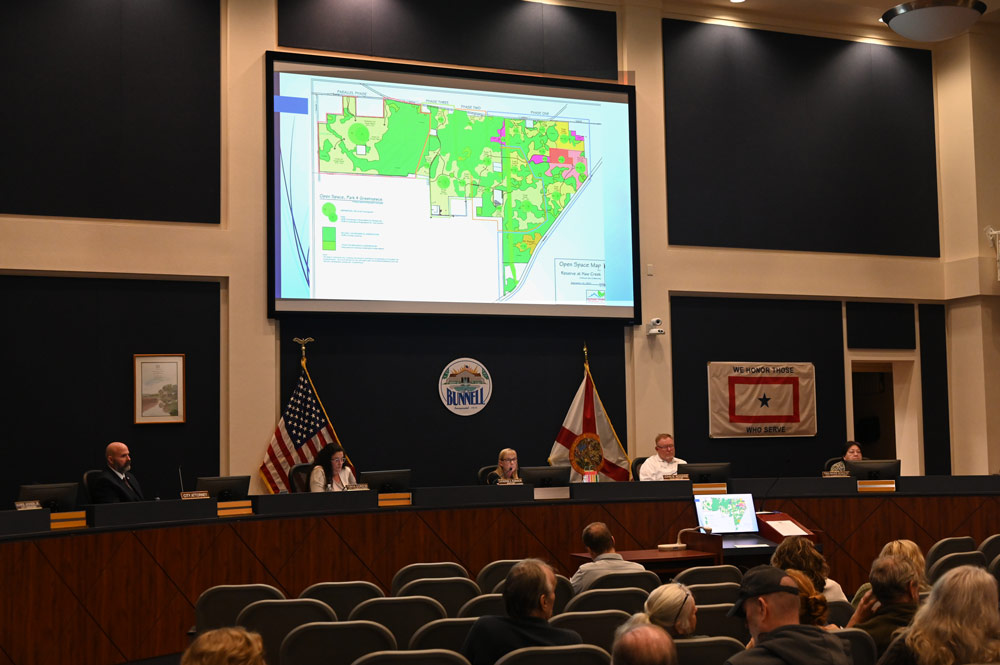

The 8,000-home development called Reserve at Haw Creek in Bunnell may proceed, but it will have to respect the city’s minimum requirement of 60 percent of open space.

Rejecting a developer’s claim that his due process was violated or his veiled threat to build more apartment buildings if his request was rejected, the Bunnell City Commission on Monday voted 3-2 to deny an exception that would have allowed reducing open space at the Reserve at Haw Creek from 60 percent to 50 percent. The result was a remarkable display of the power of persuasion as the arguments of a commissioner and members of the public clearly influenced at least one, and possibly two commissioners to switch sides along the way.

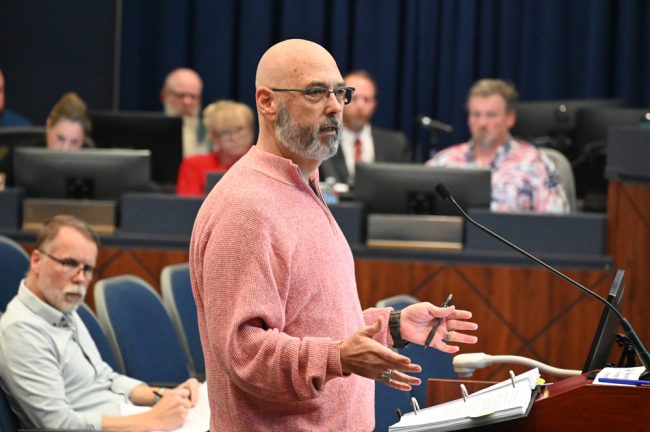

Northeast Florida Developers has submitted plans to build the 6,000-to-8,000-home development (up from 5,000 to 6,000 just a few months ago) on 2,800 acres west and south of the urban center of Bunnell. Chad Grimm, who represents the company, argued to the city’s planning board last November that the exception, or variance, was necessary to allow for more single-family homes, which is more profitable. Otherwise, the company would have to make up in height what it lost in spread–meaning that it would have to build more apartments.

The planning board unanimously rejected the request, citing city rules. To win such exceptions, developers have to prove that they would face “hardship” otherwise–itself an objective set of criteria. The developer did not do so in this case. Northeast Florida Developers appealed the decision to the city commission. Monday’s vote upheld the planning board’s decision, denying the appeal. (See: “Colossal 6,000-Home Plan in Bunnell is Now 8,000 Homes, and Developer Wants to Cut Open Space by 10%.”)

“This just isn’t right for our city,” Commissioner John Rogers said. “Our responsibility is to ensure this development aligns with the community needs, the infrastructure, the capacity, environmental, sustainability. I think that we’ve been more accommodating thus far. And when you look at State Road 11, State Road 100 and U.S. 1 and the traffic that’s on there now, you’ve got to think about the future. And some of us are going to be here for a long time. We don’t have a house for sale. So we’re going to have to deal with this in the future.”

The requested exception was opposed by every one of the dozen residents who addressed the City Commission. Many are property owners either in enclaves within the proposed development or on its immediate rim, among them Larry Rogers and his family, on County Road 65 (he is no relation to John Rogers).

“When we go for the land development code and you change it to 50 percent from 60 percent, every developer that comes next,” Rogers said, will ask for the same exception. “So when that happens one day in the future, that precedent is going to be set. They’re going to come right here and they’re going to say, hey for the Haw Creek Preserve folks, you let them do it for 50 percent. Now we want to do it too. That is the slippery slope that is going to be the problem for us going forward.

“And all you’re doing today is upholding what is already in the code for the city that the developer was already aware of prior to them ever purchasing the land,” Rogers continued. “So anything that we are being asked to do now is simply for the benefit of the developer, and this piece of it is unnecessary and should be a simple decision for this commission, because your staff already says it’s not right. Clearly the public doesn’t believe that it’s in the public interest.” (The city administration actually recommended approval of the variance, even though, of its own admission, all the criteria were not met for a “hardship.”)

The vote was the culmination of an 80-minute segment of discussions, debates and public participation. Initially it looked as if the commission would grant the appeal. Commissioners Tina Marie-Schultz and Tonya Gordon immediately moved and seconded to grant the appeal before Commissioner Rogers stepped in to slow things down, and the public and Grimm spoke. Even when Mayor Catherine Robinson heard from her colleagues afterward, and spoke herself, about the item, she did not tip her hand and seemed, if anything, to be leaning in favor of the developer’s request–as did Commissioner Pete Young.

There was some confusion when it came time to vote, since approving the Schultz-Gordon motion meant both granting the appeal and overturning the planning board’s decision, so commissioners in a Clintonian may have been puzzled as to the meanings of “is,” “yea” and “nay.” In the end, Robinson, Rogers and Young voted against the motion, thus upholding the planning board’s decision and denying the reduction to 50 percent. Schultz and Gordon–the two commissioners who are stepping down at the end of their term in march, and so will not again face voters–voted for their motion. Robinson is running for re-election.

The Reserve at Haw Creek is Flagler County’s single-largest proposed development since ITT planned Palm Coast in the late 1960s. Once built, it will have increased Bunnell’s population sixfold (assuming the maximum number of homes stays at 8,000), and change the city’s politics, character and economy. But if commissioners are hoping for it to be the city budget’s holy grail, they will be disappointed. Commissioner Rogers cautioned that development doesn’t pay for itself, and echoed City Manager Alvin Jackson’s analysis about Grand Reserve, the 800-home development that has been growing on the east and north side of the city for the past 15 years and that was supposed to enrich city coffers with a surplus of property tax revenue.

It has done no such thing.

“Basically, looking at our numbers, only 40 percent of the parcels actually pay the taxes,” Jackson said–a somewhat inaccurate figure: based on the 2024 tax roll, 51 percent of Bunnell properties pay taxes, according to Property Appraiser Jay Gardner.

“So without future development to generate those funds to run the city, you won’t have a city,” Schultz said, asserting the opposite of what Rogers and Jackson were saying: that development will pay the city’s bills.

Addressing the commission, Grimm framed his request as a matter of economics. He said the development was building its own infrastructure, at its own expense, before turning it over to the city. But to do that, it would have to be a viable proposition. He explained that 1,000 housing units hinged on getting open space knocked down 10 percent. He needs those extra 1,000 units to make the development profitable (or viable). But it would be more so if he could build single-family homes, which are more profitable than apartments. If he were denied the variance, he would have to build more apartments.

All five commissioners disclosed that they had met one-on-one with the developer ahead of the meeting. It’s not uncommon for elected officials to meet with developers as proposal wends its way through regulatory steps. But it is unusual and ethically questionable for elected officials to meet with developers as a quasi-judicial appeal is pending before their own board. It is not much different than if a judge were to meet with prosecutors in chambers to hear their preferences in a case, though local officials have all but normalized the practice.

Pressing the case for his appeal, Grimm claimed to the commission that “we were not able to make a presentation” to the planning board, and that he could only “answer questions out of context.”

That’s not entirely accurate. City staff made a detailed, five-minute presentation outlining the developer’s variance application, the relevant rules that apply to variances, and the city’s position, including the administration’s recommendation that the variance be granted. Grimm then was at the podium for 18 straight minutes, answering in detail what board member Lyn Lafferty described as her “barrage of questions.”

“That was a lot,” Grimm said.

But his presentation and his answers to the questions had allowed him to make every point he’d end up making before the City Commission. He was free to provide any context he wished to the questions, since the burden was on him to justify the variance. If anything, he provided more specific information to the planning board than he did to the commission, perhaps because commissioners had had the benefit of closed-door meetings, which of course denied the public a chance to hear those details, if they are not verbalized at the meeting. Either way, Grimm at no point raised any issue of due process to the planning board, or not having enough time to speak there, or not addressing issues he wanted to address.

Grimm also claimed that the variance request and the zoning request that was also before the planning board, and that has been deferred to a January meeting, were “linked together, essentially one and the same.” They are not. A variance is its own item. It may well affect a rezoning application. But from the city’s perspective, a variance has to be dealt with independently, based on its own criteria.

By conflating the two, Grimm was using the planning board’s decision to defer its decision on rezoning to make the claim, again unsupported by the nature and breadth of Lafferty’s questions, that the planning board somehow “didn’t understand” what it was doing. “I challenge or question whether the board fully understood what it was that they’re actually voting on,” Grimm told the City Commission, a statement planning board members likely would not take kindly.

Nevertheless, in an unusually sharp rebuff of her own planning board members–and what appeared to be an echo of the developer’s talking points–City Commissioner Tina-Marie Schultz said the planning board “did not take the opportunity to be correctly educated as to the process and what needs to be done.”

“I would like to think that our planning and zoning board knew what they were talking about,” Rogers said. “Who’s the attorney on that board?” he asked. Paul Waters, who is also the City Commission’s attorney, raised his hand. “Okay, Mr. Attorney, did they not know what they were talking about?”

“Commissioner, they had all the materials and everything they needed to make a decision,” Waters said.

“I believe they made a sound decision. As a matter of fact, it’s my opinion that this doesn’t satisfy the requirements for this variance, the statutory requirements,” Rogers said. The other Rogers, the resident of County Road 65, called claims of due process violations “absurd” and “preposterous.”

Wallingford says

I applaud the Commissioners for showing the Developer that it is them who set the narrative not the other way around. Our House; Our Rules

Billy says

Finally some people/council 3 that will stand up!

Dennis C Rathsam says

WOW A city with BALLS! I tip my hat to you for standing up for your tax payers! To hell with these builders, they don’t live here. And don’t give a ratts ass about you, its all about the money! Just look to the north, where Palm Coast stands. A parking lot 1/2 the day & traffic out the ass. Houses & apartments slipping in everywhere… You see Palm Coast mayor & council, have no balls, never did, all we got here is marbles, & that’s being generous. Need a storage unit??? we got plenty, how bout a gas station??? WOW we have plenty of them too! I hope our new mayor,s elevator goes to the top floor, because here in Palm Coast we,ve been stuck on the 4 the floor!

FlaPharmTech says

This is insane. Bunnell does not have the infrastructure to support this development, nor do the citizens of Bunnell want this. Enough with greed!

PHIL says

The infrastructure must be modernized, expanded, and repaired before we can construct additional residential units. Are these developers willing to wait for the roads to be widened to accommodate 8,000 more homes? Probably not. Perhaps we should limit expansion until our city’s infrastructure can support a population of 200,000. With 130,000 people already on the roads, it’s getting crowded.

Ed P says

As the clock ticks on and the housing market softens, reality may become a larger factor. The scope of this project, location, and timing will probably contribute to their inability to ever complete the build 100 %. Will the build even start?

Florida Girl says

Did you know how the area “Haw Creek” got its name? The area once was heavy with Native Americans, then later heavy with Florida Natives. This area got its name due to the natives picking “haw” berries out there. They once grew everywhere along with a plethora of other edible berries in that area. Generations of my family have harvested out there. I hate to see it lose what we once so dearly loved.

I guess this too will be folded into the earth and forgotten about.

Lisa J Ferreira says

When developers “gift” infrastructure to municipal government the municipal government MUST be ready to make repairs and upgrades immediately. Too often the developers use shoddy materials and compromise specifications. Construction inspection MUST be done during installation. Inspection MUST be performed at a cost to the municipal government. Inspection MUST occur before the gift is made. A depreciated defective gift bears a huge price tag. Relying on the proposed gain in property tax is net zero or negative. The municipal government should consider a special district where responsibility for infrastructure is managed and maintained by the district for years, before accepting the infrastructure.

Dbhammock says

If the developer needs more space and more houses, it says to me they have a poor financial planning department. When you come to a city in the first place asking for approval based on a set of numbers and you get it approved, you move forward and start building. You can’t say, oops, we figured it all wrong. Sounds like a bait and switch tactic to me. Glad they voted it down. They shouldn’t give them. More than 6,000 residences and 60% open space.

Susan says

They probably should have developed that large area over the next 50 years to 75 years to let some other Generations get their hand in it plus modernization of homes felt it just doesn’t make sense to rip it all apart at once or they could preserve some of it is the original farmland but Money Talks and the politician love is money especially easy money that he doesn’t have to work for like iron workers work hard

Stop The Insanity says

Where are the high paying jobs that will be needed to support living in those homes/apartments? Surely not all 8,000 of them will be retires? Once Palm Coast gets built out with the already approved thousands of homes/apartments, who would want to live here anymore? You won’t be able to get from point A to point B. The traffic will be unbearable. Our infrastructure can’t sustain it.

Jamie says

My husband and I retired and moved to Palm Coast in 2018. It was the worst mistake of our lives. We were from a small town in New England. Palm Coast is so overpopulated heavily trafficked when it takes you 20 minutes to drive 1 mile there is a problem I was shocked at all the crime and high cost of living there. Luckily, we were able to move out last year and headed back to the New England area in the small northern towns, and we love it!