The case of Bacchus, the chocolate-colored Labrador dog Flagler County declared dangerous after the dog bit an 8-year-old child in the face almost three years ago, may finally be headed toward a settlement. And a precedent-setting circuit court decision the county considers erroneous may be nullified.

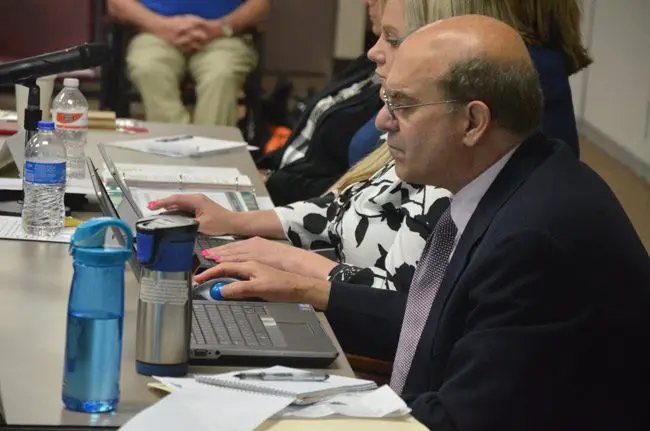

The County Commission Monday voted unanimously to accept a settlement County Attorney Al Hadeed is preparing with the dog’s owners, Jay and Dawn Sweatt, who live on Remington Road in the Eagle Rock subdivision, near Plantation bay. The settlement would eliminate the dangerous-dog designation but impose a set of conditions the Sweatts must follow if they are to keep ownership of Bacchus.

On its face the case involves only one dog, two families and the county. In reality, the case has become almost peripheral to its implications for county authority, who gets to define that authority and whether a circuit court erred in an attempt to re-define the authority. The county believes that its authority has been subverted by an improper court order. It’s fighting this case to restore that authority.

If accepted by the Sweatts, the settlement would also presumably nullify a circuit court order written by Judge Scott DuPont last year that the county finds inadmissible, because it rewrites procedural rules that define how county government handles dangerous dog cases, and by extension possibly other quasi-judicial proceedings. DuPont declared the county’s handling of the dangerous dog case improper, in part because, the judge claimed, some people who spoke at the commission hearing should not have spoken, and Hadeed himself should have taken a side and advocated for or against the dog owners—a position Hadeed finds improper in his role as county attorney.

DuPont ordered the county commission to rehear the case within the parameters he set out. That was last summer. But the county appealed the decision to the Fifth District Court of Appeal

“We were troubled very much by the circuit court order,” Hadeed said, more explicitly criticizing DuPont’s order in a memo to commissioners: “In overturning the board’s decision, the Circuit Court misconstrued the County Administrative Hearing Ordinance as well as principles related to quasi-judicial proceedings,” Hadeed wrote. “Because it was the first time a dangerous dog case has been appealed to the judicial system, the Circuit Court’s ruling had the effect of establishing precedent as to how the county will have to handle dangerous dog cases under the county code. To correct the errors, the county appealed the ruling to the Fifth District Court of Appeals.” (See details of the appeal here.)

Rarely does an attorney so explicitly call out a judge’s knowledge of the law—especially a local judge with whom that attorney will almost inevitably be facing again in subsequent cases. But DuPont is embroiled in a controversy of his own, having spent much of the past year defending against a series of charges from the Florida Judicial Qualifications Commission that he may have acted improperly inside and outside the court. The qualification commission’s decision is expected any day. (Hadeed later clarified that DuPont’s case before the qualification commission “would not have influenced my writing of the memo. I have criticized courts before.”)

It is unlikely that absent that context and the possibility of a settlement, Hadeed’s memo would have taken the liberties it did against DuPont’s ruling. The Sweatts recently stopped being represented by Vincent Lyon, the Palm Coast lawyer who’d handled the case for much of its duration, and have been contending with the appeal by representing themselves (and requesting extra time to respond, which has been granted). That may be playing into their decision to settle.

The slog continues. Bacchus was 2 years old at the time of the incident and is now middle-aged, in dog years. One of the county commissioners who heard the case, and the only one to dissent from declaring the dog dangerous in a September 2015 hearing, has since died. Two others have been voted out.

“We always do try to pursue settlement, all parties should, all lawyers have an obligation under our bar professional rules to do that,” Hadeed said. “What they’re trying to avoid is avoid the label of a dangerous dog on their dog. They’re willing to take the steps to minimize the risks of public harm.”

If the dog were labeled dangerous and bit a person yet again, the Sweatts could ace a felony charge, though Hadeed said that’s unlikely, given the alternative of euthanizing the dog.

The settlement’s conditions would be as follows: Bacchus would not have the dangerous dog designation that the county commission imposed. Bacchus had not been vaccinated for rabies at the time of the incident, requiring the 8-year-old boy to go through painful vaccinations of his own. The Sweatts will be required to provide proof of vaccination to the county. The dog will have to be confined behind a physical fence, not just an electrical force field, as was the case previously—a force field the dog violated (Bacchus once charged a neighbor who fired his gun as a warning to the dog, which never left the property, an incident that prompted the Sweatts to call police. An earlier version of this story incorrectly attributed the gunshot to a law enforcement officer).

The dog must also be muzzled and leashed if taken beyond the fence or the house. It must go through behavioral training—the equivalent of anger management for dogs—and must have an electronic implant that would enable authorities to track it should it run away again, as it has on two previous occasions. If the dog is given away or sold, the Sweatts, must notify county officials. And if he attacks someone again, he must be turned over to county Animal Services for evaluation.

Hadeed said the Sweatts have essentially agreed, if tentatively, to the conditions.

“Being an animal lover,” County Commissioner Nate McLaughlin said, “it’s difficult to say put an animal down, but being a lover of humanity and children and public safety also, which really rises above that, of my love of animals, I think that Mr. Hadeed has come to a reasonable and right conclusion on this.”

Hadeed said that whether the appeal goes forth or not, he intends to submit clarifications to county ordinances as to the county attorney’s role in such proceedings. Hadeed was particularly bothered by DuPont’s order that the county attorney should have taken sides in the dangerous dog case. County ordinances don’t spell out the attorney’s neutrality. That was not thought to be necessary—until now.

“Even if we were permitted to do that, I doubt that that’s what you would want me to do,” Hadeed told commissioners. “You wouldn’t want me to be the champion of one side or another because you’re ultimately the judge. What you would want me to do is to make sure that whatever is going on is proper and legal.”

Vincent says

The County does need to clarify the role of the county attorney. While mr. Hadeed did not personalltake a side, his employee did. The County attorney office sent an attorney employee to present arguments and evidence at the hearing before the neutral hearing officer who found in favor of the Sweatts.

Anonymous says

Let’s wait on the results of the appeal before agreeing to anything….the County again may be told they are WRONG! Here is a prime example of Hadeed and McLaughlin being WRONG https://edca.1dca.org/DCADocs/2016/0724/160724_1284_02022017_020937_i.pdf

Ben Hogarth says

It is extremely concerning when a Judge, particularly one who is in a position to make determinations and rulings that would impact the way a county conducts business, is actually advocating for against impartiality for the county attorney. And his ruling in this case was reflective of that belief.

If this is not an egregious retreat from core legal ethics, it’s a moment of very poor judgement (no pun intended).

Al did the right thing and I couldn’t agree more with his choice to call the judge out in the response. It errs on the side of ridiculous that a circuit court judge could make a determination where the requirement redefines the manner in which a quasi-judicial county hearing must proceed. State law already governs this and I don’t remember reading anywhere in statutes that a county attorney must “take a side.”

When we talk about judicial overreach – this is the kind of example we mean.